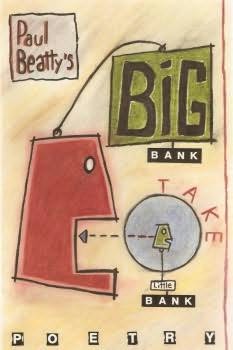

Having read both Eliot’s article and Thomas’s article, it seems to me that Eliot is focusing on the larger too-big-to-fail banks while Thomas is considering the plight of smaller, less politically connected banks.

The Regulatory Charade

Washington had the power to regulate misbehaving banks. It just refused to use it.

By Eliot Spitzer in Slate

Does it strike you as odd that the American government has invested $115 billion in TARP money alone in Citibank, JPMorgan Chase, and Bank of America, fully 70 percent of their market cap ($164.5 billion, as of March 30), yet we have virtually no say in the management or behavior of these banks? Does it seem even odder that these banks are getting along extremely well with the government regulators who should be picking them apart for having destroyed the economy and financial system?

There is a grand, implicit bargain being struck in our multitrillion-dollar bailout of the financial-services sector. Those in power in D.C. and New York are pretending the bargain is: You give us trillions, and in return, we fix this industry so the economy recovers and this never happens again. In fact, the bargain is much more alarming: Trillions of dollars of taxpayer money will be invested to rescue the banks, without the new owners—taxpayers—being allowed to make any of the necessary changes in structure, senior management, or corporate behavior. In return, the still-private banks will help the D.C. regulators perpetuate the myth that regulators didn’t have enough power to prevent the meltdown. In sum, banks get bailed out with virtually no obligations imposed; regulators get more power and a pass on their past failures. The symbiosis of the past decade continues.

We already see regulators, supported by investment and commercial banks, calling for expanded power—specifically the ability to reach hedge funds and other "private equity" with more oversight and to seize institutions that pose systemic risk with greater alacrity.

Each is a worthy regulatory idea. But each is essentially irrelevant to the problems that got us where we are. The new line from Washington and Wall Street is that hamstrung regulators lacked the power to stop malfeasance before the crisis. This is wrong. Washington had enormous power over the misbehaving investment banks, commercial banks, and ratings agencies. It just refused to use that power.

Financial-services companies have been given multiple blank checks, worth hundreds of billions, yet there have been virtually no mandated changes in management, behavior, or lending practices. Nor have bondholders in that sector been required to take a haircut, as they have been elsewhere. GM was required to replace its CEO, Rick Wagoner, and auto company stockholders, bondholders, and unions have all been required to take substantial haircuts…

Instead of creating new regulations and laws that don’t really address the root causes of the crisis, we should look to a simpler but more fundamental way to limit systemic financial risk and simultaneously create a healthier financial marketplace: If it is too big to fail, break it up. We should not let any private institution become so big and central to the financial system that taxpayers become its guarantor. The problem is that this model doesn’t fit into the secret grand bargain. On the contrary, the entire premise of the grand bargain is that the companies that were already too big to fail have been allowed to get even bigger. Socializing risk while privatizing gain—which is what having more and bigger "too big to fail" institutions guarantees for the future—doesn’t work in the long run. Too big to fail, quite simply, is too big.

Full article here.