Not whether the S&P is overpriced, but by how much.

How Overpriced Is The S&P 500?

Courtesy of Mish

Courtesy of Mish

Inquiring minds are wondering How Overpriced Is The S&P?

It’s an excellent question given bulls feel the market is headed much higher while the bears feel the opposite after a remarkable 50% rally.

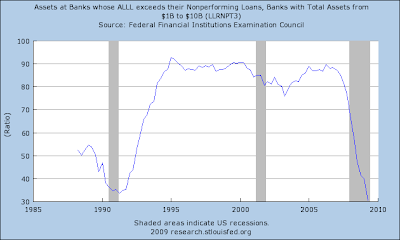

Let’s start off with a look at the financial sector where Allowances for Loan and Lease Losses (ALLL) have plunged even though non-performing loans soar.

To understand the importance of ALLL, inquiring minds are reading a description of Allowances for Loan & Lease Losses.

Businesses try to predict, on an ongoing basis, the amount of loss in their accounts. They take periodic charges to earnings to better match losses to periods when they occurred. Banks do this as well. They use current income, through the provision for loan and lease losses, to create and build a reserve to absorb losses.

The ALLL can be increased another way. When the bank collects on previously charged-off loans, the amount recovered goes into the ALLL.

Charged-off loans decrease the ALLL. If a bank decides it has overestimated its potential loss exposure, it can choose to reduce its ALLL and add the amount to its income. This is known as making “reverse provisions” for loan and lease losses, because the bank decreases the allowance, or reserve amount, rather than increasing the provision. It is rare for a bank to make a reverse provision, however, because of the imprecise nature of determining an appropriate reserve.

One last point to remember with respect to the reserve is that the ALLL is a general reserve. Therefore, even if a bank analyzes and estimates the loss on each loan, the allowance is there to absorb all losses in the loan portfolio and is not specific to a particular loan.

With that backdrop, let’s take a look at a few charts. Click on any of the following charts to see a sharper image.

Assets at banks whose ALLL exceeds Nonperforming loans

Banks with Total Assets from $1B to $10B where ALLL exceeds Nonperforming loans

Banks with Total Assets from $1B to $10B (Pacific Region) where ALLL exceeds Nonperforming loans

Banks with Total Assets over $20B where ALLL exceeds Nonperforming loans

Remember that allowances for loan losses will decrease as charge offs increase. However, the above charts are in relation to non-performing loans.

Because allowances for loan losses are a direct hit to earnings, and because allowances are at ridiculously low levels, bank earnings have been wildly over-stated.

Bank Profits Too Good To Be True

Flashback April 16, 2009: Wells Fargo’s Profit Looks Too Good to Be True: Jonathan Weil

What sent Wells shares soaring on April 9 was a three-page press release in which the San Francisco-based bank said it expected to report first-quarter net income of about $3 billion. Wells disclosed few details of what was in that figure. And by pushing the stock up 32 percent that day to $19.61, investors sent a clear message: They didn’t care.

Dig below the surface of Wells’s numbers, though, and there are reasons to be wary. Here are four gimmicks to look out for when the company releases its first-quarter results on April 22:

Gimmick No. 1: Cookie-jar reserves.

Wells’s earnings may have gotten a boost from an accounting maneuver, since banned, that it used last year as part of its $12.5 billion purchase of Wachovia Corp. Specifically, Wells carried over a $7.5 billion loan-loss allowance from Wachovia’s balance sheet onto its own books — the effect of which I’ll explain in a moment.

Once it took control of the reserve from Wachovia, Wells was free to start dipping into it to absorb new credit losses on all sorts of loans, including loans Wells had originated itself. (Think of a child raiding a cookie jar.)

The upshot is that Wells could get by with reduced provisions until the $7.5 billion is used up, boosting net income.

Another quirk: The reserve was related to $352.2 billion of Wachovia loans for which Wells was not forecasting any future credit losses, according to Wells’s annual report.

Weil goes on with three other highly suspicious (at best) practices by Wells Fargo, including a balance sheet holding of $109 billion of "other assets". Weil writes:

"The footnote says the largest component was a $44.2 billion bucket that Wells labeled as “other.” Yes, that’s right: The biggest portion of “other assets” was “other.” And what did this include? The disclosure didn’t say. Neither would Bernard.

Talk about a black box. That $44.2 billion is more than Wells’s tangible common equity, even using the bank’s dodgy number. And we don’t have a clue what’s in there.

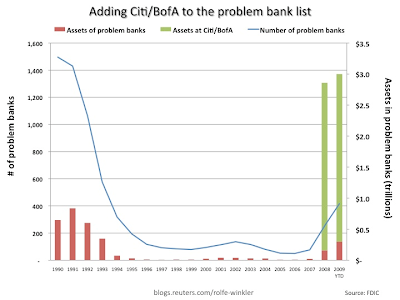

FDIC Problem Bank List Soars To 416

For a nice discussion of some of the problems facing the financial sector, please consider For FDIC, a long tunnel and little light by Rolfe Winkler at Option Armageddon.

FDIC’s problem bank list grew to 416 at the end of last quarter. These banks have $300 billion of assets.

In total, FDIC estimates the banking sector is wrestling with $332 billion worth of loans and leases on which borrowers have stopped making payments. That excludes hundreds of billions worth of underwater loans that may be current now but will ultimately default. Many banks, including the largest ones, are likely to struggle for some time.

Citigroup and Bank of America have received hundreds of billions of dollars of government support, but, precisely because of that support, they’re not on the FDIC’s list. Adding them to it would multiply total problem assets 10 times, to $3 trillion.

Asset prices aren’t going back to their highs of 2006-2007, so loans held against them will be generating losses for years. The FDIC may raise enough cash from banks to fund depositor losses in small and medium-sized banks, but it is clear that the biggest banks are far too large for them to handle.

As a result, the government’s emergency rescue measures aren’t going away for a while. And taxpayers should expect to be writing fat bailout checks to the financial system for years to come.

America’s Japanese banks

Inquiring minds are reading America’s Japanese banks also by Winkler.

A banking system loaded down with hundreds of billions of dollars worth of unrecognized bad debt — Japan in the 1990s? No, it’s the United States today.

And where are American banks hiding their losses? Among other places, in their loan portfolios. Banks have written down billions in toxic securities, but many toxic loans are still carried at close to full value.

According to data published by the Federal Reserve late last year, banks are carrying $3 trillion of residential real estate loans and $1.7 trillion of commercial real estate loans on their books for a total of $4.7 trillion. Dan Alpert at Westwood Capital thinks as much as a fifth of that total could be uncollectable.

Banks argue that loans should not be marked down if they’re still “performing.” As long as borrowers are meeting their contractual obligations, there’s no reason to take a writedown. The problem is, this gives banks an excuse to extend, amend and pretend. They can make concessions on loan terms or delay foreclosure notices, if only to maintain the fiction that borrowers will make good.

With real estate prices likely to fall, and stay, 40 percent below the peak, borrowers have a big incentive to renege on their side of the bargain. This is how we become Japan. Emergency bailout facilities allow banks that otherwise would have failed under the weight of bad loans to hold those loans to maturity — pretending the bad ones will be paid off in full over time.

In reality, many loans will default and banks will bleed capital for years. Take commercial real estate. As the Congressional Oversight Panel has reported, few CRE loans that were originated at the peak will qualify for refinancing when they mature. Banks can pretend they will, carrying the loans at values far above what will ever be paid back.

So what do we do? We can start by eliminating government guarantees that allow banks to avoid dealing with the problem.

As things stand, the biggest banks have no incentive to write down loans because the Federal Reserve, Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation and Treasury Department have, in effect, promised them unlimited financing to hold loans to maturity.

As the Japanese can tell you, this is just a recipe for stagnation. Thanks to a debt bubble that authorities refused to deal with decisively, that country is now entering its third consecutive lost decade.

S&P 500 Earnings

Given that loan loss provisions directly affect earnings. Let’s take a look a PE chart of the S&P 500 from Chart of the Day.

That chart was from earlier in the month. Nearly all companies have now reported and the PE is down to 127.43. If that sounds preposterous you can check the S&P 500 Excel Spreadsheet right on Standards and Poors.

Real vs. Operating Earnings

The chart above is based on actual reported earnings. Unfortunately it’s difficult to find anyone stating P/E ratios based on actual earnings. Instead, because the media and investor bias tends towards being 100% invested 100% of the time, nearly all estimates you see are based on "operating earnings".

Barron’s had an excellent article on this subject in May of 2008. It is as relevant today as it was then. Please consider What’s the Real P/E Ratio?

There are two main earnings numbers that Wall Street uses when discussing valuations — "reported earnings" or "operating earnings." Typically, the bulls use "operating earnings," and the bears use "reported earnings" because operating earnings are higher and reported earnings are lower. Also, it makes sense for the bears to use the past 12 months of earnings because they are usually lower, and for the bulls to use forward operating earnings to help make their case. Using the last 12 months is much more consistent, since it avoids dependence on estimates of earnings.

Operating earnings exclude write-offs, while reported earnings include write-offs. That is the only difference, but it’s a difference that is getting much more important. As recently as the early 1990s, operating and reported earnings were virtually the same. But then we entered the greatest financial mania of all time, and the earnings numbers diverged.

There were so many write-offs by companies making unwise investments and then undoing them that operating earnings grew much faster than reported earnings. The write-offs that had been sporadic and unusual became common for many companies.

Using operating earnings is now like playing in a golf tournament that doesn’t count any penalty strokes for hitting the ball into a water hazard or out of bounds.

Over the past 75 years, most market peaks topped at around 20 times reported earnings, and the troughs occurred at around 10 times earnings. The financial mania of the late 1990s pushed P/Es to over 40 times reported earnings, and the following bust never brought P/Es below 18 times reported earnings.

There’s more we can do to make sense of earnings: The best way to measure present earnings and future earnings is to smooth them out over long periods. Earnings can grow at only approximately 6% a year over the long term. The trend is limited by the growth in real GDP plus inflation. And long term, real GDP cannot grow faster than the increase in the labor force plus the increase in productivity.

If you don’t accept this, look at a long-term chart and draw a 6% growth line through the earnings. It is clear that earnings sometimes rise above the line and sometimes fall below it, but earnings always revert to the 6% mean.

Going back to 1950, every instance where actual earnings rose above trend-line earnings was followed by a period where actual earnings went well below trend-line earnings.

Creative Destruction

Creative Destruction

Please bear in mind that historical long term trends are just that. Intermediate-term, it is imperative to factor in demographics, changing consumer attitudes towards debt, willingness and ability of banks to lend, overall debt levels, etc.

I have discussed consumer attitudes many time, most recently in Creative Destruction.

Factors Sealing The Deflationary Fate

The five month, 50% rebound in the S&P 500 was certainly spectacular. However, the more important question is where to from here?

Take a look at Japan’s "Two Lost Decades" for clues.

Creative destruction in conjunction with global wage arbitrage, changing demographics, downsizing boomers fearing retirement, changing social attitudes towards debt in every economic age group, and massive debt leverage is an extremely powerful set of forces.

Bear in mind, that set of forces will not play out over days, weeks, or months. A Schumpeterian Depression will take years, perhaps even decades to play out.

Thus, deflation is an ongoing process, not a point in time event that can be staved off by massive interventions and Orwellian Proclamations "We Saved The World".

Bernanke and the Fed do not understand these concepts, nor does anyone else chanting that pending hyperinflation or massive inflation is coming right around the corner, nor do those who think new stock market is off to new highs. In other words, almost everyone is oblivious to the true state of affairs.

How Overpriced Is The S&P?

Take another look at those charts kicking off this article. Factor in the analysis of Winkler and Weil. Factor in demographics, consumer attitudes, etc. Factor in global wage arbitrage. Factor in loan loss provisions that have only one way to go, up. Factor in consumer debt levels, realizing that consumer spending is 70% of the economy.

Do the forward earnings estimates you hear from bulls make any sense to you? They do not make sense to me. While it’s hard to put a price tag on any of those components, we can look at Japan as a model as I have suggested on many occasions and Winkler is suggesting now.

If you have not yet done so, please consider Effect of Household Deleveraging on Housing, Consumption and the Stock Market. Here is a snip pertaining to Japan, but there is much more in the article to see.

Nikkei Stock Index 1980-Present

click on chart for sharper image

A look at the Nikkei shows that Japan has already lost two decades since the peak in 1990. It is likely the US follows the same general pattern.

Of course some huge innovation like the internet could come along that would create enormous profits and employ millions of highly paid workers. However, the odds of that are extremely small.

Thus, the risk/reward scenarios of long term investing are awful based on fundamentals alone. Traders however, will have many opportunities in both directions.

All things considered, I suggest the S&P 500 is easily 50% overvalued based on what we know now. That is not a prediction the S&P will be cut in half, rather it is my belief that it should be cut in half. Given that I have seen estimates as low as 200, I am not "SuperBear".

However, the reality is no one really knows what innovation is (or is not) coming, nor can anyone say for certain what valuations investors are willing to place on earnings. There are also foreign Central Bank issues to fact in. With that in mind, the S&P could easily meander around this level for a decade while earnings catch up to what are now very poor valuation metrics.

As always, traders need to keep an open mind and not get locked into any scenario. Long-term investors will have to take what they get. Unfortunately, I suggest those results are not likely to be very pretty.

*****