It has long been recognized that the global financial structure — built as it is around the dollar as the world’s reserve currency — has a fundamental design flaw that makes it inherently unstable. The problem was first identified back in the early 1960s by the Belgian-American economist Robert Triffin, in “Gold and the Dollar Crisis.” Writing about Europe’s accumulation of dollars, he argued that the system carried the seeds of its own destruction. Foreigners could acquire dollars only if the United States ran current account deficits — that is, spent more than it earned. But lending money to someone who lives beyond his means has obvious dangers, and the same is true of countries.

Thus, the American deficits necessary to supply dollars to the world for international transactions simultaneously undermined confidence in the currency. It was only a matter of time, Triffin predicted, before the system would be hit by a crisis — which it duly was in the early 1970s.

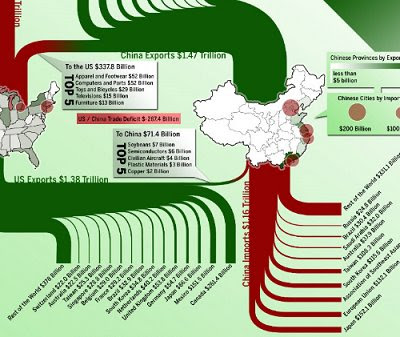

In the wake of the 1997 financial crisis there, countries in East Asia set out to build up war chests of dollars as insurance against domestic banking runs or downturns in the global economy. At about the same time, China embarked on a program of export-led growth, engineered by keeping its currency artificially low.

Interpretations of what happened next differ. Some argue that to absorb these goods from abroad while avoiding unemployment at home, the United States very consciously stimulated consumer demand. The country, in effect, was forced to live beyond its means. Others believe that the Fed misread the fall in prices as a symptom of inadequate demand rather than for what it was — an astounding, once-in-a-generation expansion in the supply of low-cost goods — and kept interest rates low for an unusually long time, which provoked the real estate bubble.

In either case, the result was an enormous accumulation of dollars in the hands of Asian central banks. Those dollars, when invested in the American bond market, drove long-term interest rates even further down and made credit in the United States even more artificially cheap.

In either case, the result was an enormous accumulation of dollars in the hands of Asian central banks. Those dollars, when invested in the American bond market, drove long-term interest rates even further down and made credit in the United States even more artificially cheap.

The build-up of dollars abroad was also the catalyst for a remarkable transformation in the flow of money around the world. The United States found itself literally operating as a gigantic bank, taking short-term liquid deposits from countries with surpluses and investing the money in long-term, risky assets at home and abroad. The numbers involved were staggering. In 1996, the United States had international assets and liabilities of around $5 trillion. By 2007 the figure was more than $20 trillion. Like any bank, it was vulnerable to a run. The main fear was that the United States at some point would be faced with a modern-day replay of Triffin’s dilemma and would have to deal with the consequences of a collapse in confidence in the dollar.

One scenario has the world adjusting smoothly to the new realities. American consumers, tapped out by debt, tighten their belts. The Asian economies reconsider the wisdom of relying so heavily on exports to drive their growth and focus more on domestic consumption. And with less money to recycle, international banks, which had done such a poor job, are cut down to size.

But two dangers could make the current bad situation worse. One is that China finds it too difficult or politically costly to restructure its economy and, despite the changes in the global market, keeps its foot on the export accelerator. Since the American consumer cannot afford to keep buying, this would set off a cycle of trade wars among Asian countries competing for ever smaller markets.

The second is yet another version of Triffin’s dilemma: if even a small fraction of foreign holders of dollars were to be spooked by our budgetary problems, we could have a spike in the cost of capital just when the economy is trying to recover. The risk of such a situation is clearly on the minds of Chinese policy makers. Zhou Xiaochuan, the governor of the People’s Bank of China, explicitly referred to Triffin’s dilemma in a speech this March on the need for reform of the international monetary system.

The second is yet another version of Triffin’s dilemma: if even a small fraction of foreign holders of dollars were to be spooked by our budgetary problems, we could have a spike in the cost of capital just when the economy is trying to recover. The risk of such a situation is clearly on the minds of Chinese policy makers. Zhou Xiaochuan, the governor of the People’s Bank of China, explicitly referred to Triffin’s dilemma in a speech this March on the need for reform of the international monetary system.

Until we can reconcile the export ambitions of the Asian countries, particularly China, with the import capabilities of the rest of the world, and make the volume and value of reserves less dependent on the vagaries of macroeconomic policy in one country, the risk of a similar loss of faith in today’s international financial system remains.

Liaquat Ahamed is the author of Lords of Finance: The Bankers Who Broke the World, a book about the causes of the Great Depression to be published by Penguin Press in January 2009. After working as an economist at the World Bank, he spent twenty-five years as a professional investment manager in London and New York.