The Forgotten Peg: Chinese Yuan and U.S. Dollar

Courtesy of Charles Hugh Smith, Of Two Minds

Many observers seem to have forgotten a weak dollar benefits Chinese exports due to the yuan-dollar peg.

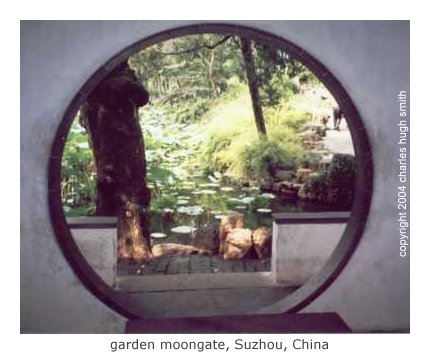

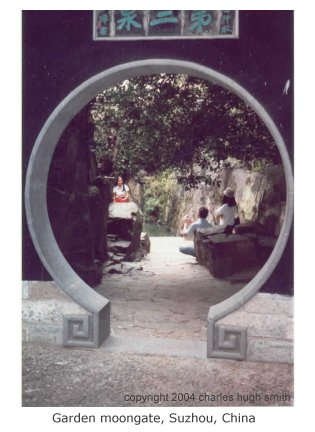

For those readers who tire of charts: enjoy!

For those readers who tire of charts: enjoy!

As the "news" continues to trumpet the decline/collapse of the U.S. dollar, many observers seem to have forgotten that the U.S. dollar is the defacto "shared currency" of the world’s largest economy and its biggest rising-star economy. Yes, the U.S. and the PRC–China. China’s currency (officially the renminbi, a.k.a. yuan) is transparently pegged to the U.S. dollar at about 6.8 yuan to the dollar, down from 8+ a few years ago.

Given that Japan is the world’s second-largest economy by most measures, and that the yen is informally pegged to the U.S. dollar (trading in a band of 90-110 yen for years on end), then it could be argued that the world’s three largest economies all "share" the U.S. dollar.

Before we explore the consequences of this, let’s look at a standard-issue "the dollar is weakening" piece: Dollar’s Slide Poised to Continue U.S. Quietly Tolerates Drop, While Trade Partners Fret; a Long List of Negatives for the Currency.

Here’s one which actually mentions the trade benefits to China of a weak dollar: Dollar weakness sends ripples across Asia: Scramble to preserve capital and the Hong Kong carry-trade redux

And just to remind everyone that China’s leaders don’t sit around tolerating circumstances which are negative for their economy: China Targets Commodity Prices by Stepping Into Futures Markets

And lastly, let’s establish the primary context of China’s leadership: 1 billion poor citizens seeking a better job/wage/life. Here is a puff piece by former U.K. prime Minister Tony Blair which makes one key point: most of China’s citizens are still very poor, and thus the leadership is obsessed with "growth" and jobs above all else: China’s New Cultural Revolution: The world’s largest country has a long way to go, but there’s no question it’s changing for the better. (WSJ.com)

Superficial stories about China are accompanied by glitzy photos of Shanghai skyscrapers and other scenes from the wealthy urban coastal cities, but the fact is that the consumer buying power of China is roughly equivalent to that of England (51 million residents).

Thus those who believe the vast Chinese manufacturing-export sector can suddenly direct its staggering output to domestic consumers in China are simply mistaken: Chinese consumption is perhaps a mere 1/10th of that needed to absorb the mighty flood of goods being produced by China.

Put yourself in the shoes of China’s leadership: what do you care about more: $2 trillion in U.S. bonds or creating jobs for 100 million people? It’s the jobs that matter, and despite its very public complaints about the slipping dollar, perhaps China doth protest too much–or more accurately, for domestic public consumption.

The consequences of a weakening dollar are neutral for Chinese exports to the U.S. but positive for exports to Japan and the European Union. Chinese exports to the EU and Japan have risen sharply in the past nine years, and a weak dollar keeps Chinese goods cheaper than rival exports in these key global markets.

Since we have many friends in Japan and my brother has lived in France for 15 years, I can report anecdotally that where Chinese goods were not all that common 10 years ago in Japan and the EU, they are now as ubiquitous there as they are in the U.S.

Since we have many friends in Japan and my brother has lived in France for 15 years, I can report anecdotally that where Chinese goods were not all that common 10 years ago in Japan and the EU, they are now as ubiquitous there as they are in the U.S.

In other words, the Chinese interest in expanding exports to Japan and the EU is more pressing than the paper loss of a few hundred billion dollars in their dollar holdings.

While Japan is importing huge quantities of Chinese goods (inexpensive due to the weak dollar), its leadership is undoubtedly working hard to maintain its own exports to China (its fastest growing export market) and the U.S.

The only way to do so is to maintain the informal peg of about 90 yen to the dollar. Below 85 yen to the dollar, few Japanese exporters can ship to the U.S. and maintain a profit. With Japanese exports cratering, the Japanese central bank is unlikely to sit idly by as exports to the U.S. implode even further.

From the point of view of Asian exporters pegged to the dollar, maintaining exports and jobs is more pressing than the value of their dollar holdings. Japan would be delighted with a 10%-20% appreciation in the dollar, as would EU exporters being decimated by the weak dollar, and China would tolerate a modest rise in the dollar as long as the rise didn’t outprice its goods in Japan and the EU.

Those calling for a full-blown collapse in the U.S. dollar might profitably ask if the dollar’s partners–China and Japan–would approve. To reckon them powerless to halt a dollar implosion would be a major mistake because the stakes are beyond high.

Yes, they could unpeg from the dollar, but in this 3-D chess game, radical actions can trigger radical (and unpredictable) consequences, and the basically conservative leaderships in Asia have too much at stake to gamble on abandoning the dollar and the U.S. market.

For the reasons stated here and the chart posted last week, I continue to foresee a significant dollar rally within the next month or two to a "Goldilocks" band–not too high but not too low, either.