Bad C’s prompts me to recycle my introduction to George Washington’s Blog’s "The Ongoing Cover Up of the Truth Behind the Financial Crisis May Lead to Another Crash":

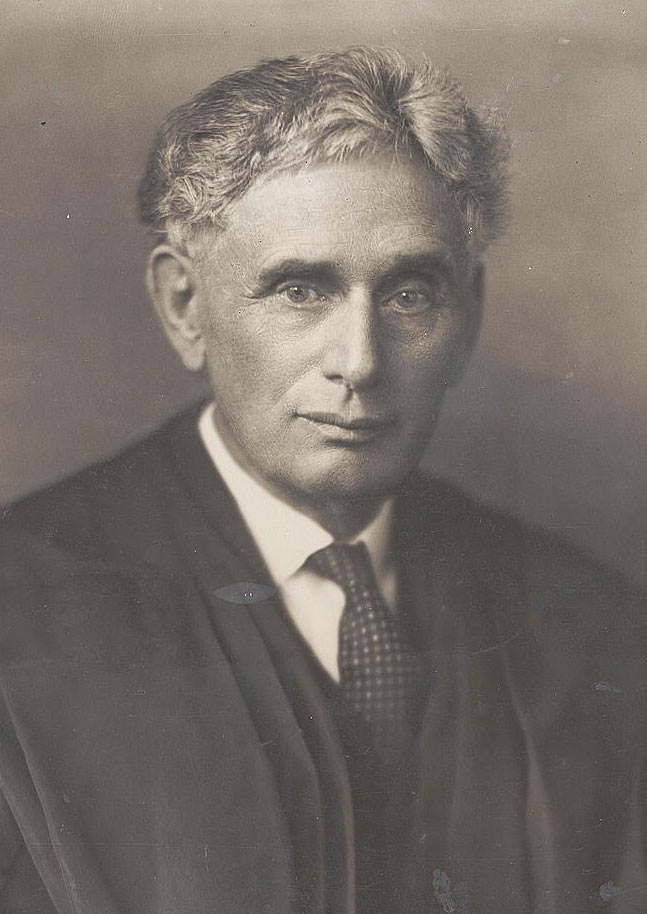

Our freedom depends on our government enforcing and abiding by the law. It’s apparent that we are headed down the slippery slope Justice Louis Brandeis describes in Olmstead v. United States (1928):

"In a government of laws, the existence of the government will be imperiled if it fails to observe the law scrupulously. Our government is the potent, the omnipotent teacher. For good or ill, it teaches the whole people by its example. Crime is contagious. If government becomes a lawbreaker it breeds contempt for law: it invites every man to become a law unto himself. It invites anarchy."

We have the Federal government’s massive and flagrant display of lawlessness, and population somewhere on the way from apathy to dependency in the Fatal Sequence cycle of civilization. – Ilene

Michael Panzner elaborates on this theme:

Bad C’s

Courtesy of Michael Panzner of Financial Armageddon

Before the era of Frankenstein Finance and the fanatical focus on fee-based income, lenders tried to hold themselves out as models of probity (for the skeptics out there, I did say "try."). Those responsible for making credit-granting decisions and looking after the interests of shareholders also demanded that borrowers meet certain standards before they would see even a dime of their employers’ money. These criteria are known as the "5 C’s of Credit," which are the

key elements a borrower should have to obtain credit: character (integrity), capacity (sufficient cash flow to service the obligation), capital (net worth), collateral (assets to secure the debt), and conditions (of the borrower and the overall economy).

In an interesting twist of fate, the firms that have traditionally decided who should get credit have been put in the position of needing extraordinary amounts of other people’s money just to stay alive. Unfortunately, based on what we’ve seen so far, including reports like those that follow, it’s doubtful whether most, if not all, of today’s troubled financial institutions would even qualify for a loan based on traditional measures of suitability — like "character," for example — if their friends in high places weren’t so intimately involved in the process.

"Wall Street’s Sham Profits" (Michael Corkery, Wall Street Journal Deal Journal blog)

My colleague Evan Newmark says that third-quarter economic growth is illusory–an economic confection created by heavily subsidized auto and home sales.

By that reasoning, what does this sham Main Street recovery say about Wall Street’s apparent rebirth? It isn’t hard to find a sham there, too.

While it is hard to unpack the nature of every profitable dollar at Goldman Sachs Group and J.P. Morgan Chase, for instance, one can make a compelling case that–like cars-for-clunkers–our Wall Street institutions are in one way or the other, also on the government dole.

The most obvious subsidy was the Troubled Asset Relief Program. While some financial institutions have made headlines for paying back TARP funds, the vast majority still owe the government billions. (TARP lent $238 billion to more than 680 banks; only 44 banks have repaid the funds, for a total of $71 billion)

Consider the other subsidies at play. In a recent Time magazine cover story, “What’s Still Wrong With Wall Street” author Allan Sloan lays them out.

“The real bailout wasn’t TARP. It was lending and guarantee programs from the Fed and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. The Fed had a mere three borrowing programs before the crisis started in the summer of 2007, when two Bear Stearns hedge funds failed. At the height of the bailout, there were no fewer than 13 programs.”

These programs enabled some Wall Street firms to borrow money at historically cheap rates, according to Sloan. At such levels, it isn’t hard to turn a profit from the spreads between borrowing and lending.

“Much of the money that taxpayers have pumped into the financial system has ended up at banks that are lending it back to the government by buying Treasury securities. Isn’t that great? We make money available to the banks at 0%, they lend it to the government at a markup, and they make money off our tax dollars, whining every step of the way,” he writes.

And let us not forget the famous bailout of AIG. Unlike TARP, AIG doesn’t need to pay back the $85 billion that the Federal Reserve Bank of New York provided to pay off the insurer’s credit default swap trades at 100 cents on the dollar.

As Bloomberg pointed out on Tuesday, Goldman received $14 billion when AIG canceled its trades. And according to this WSJ article today, Goldman was paid an additional $5.6 billion for selling the underlying investments behind its swaps to a government created toxic asset fund, called Maiden Lane III.

Other taxpayer subsidies for AIG counterparties, according to Bloomberg, include $16.5 billion that went to Societe General and $8.5 billion to Deutsche Bank (Not, of course, U.S. banks).

"Do Banks Have Something to Hide?" (Colin Barr, Fortune)

Even experts have a hard time getting a handle on how bad losses might get as the commercial real estate market implodes.

The banks have taken some lumps since the economy went bad. But some believe their biggest headaches are yet to come.

The pace at which U.S. commercial banks are adding to their loan loss reserves has slowed this year, while loans continue to go bad at a brisk pace.

Despite the optimism of lenders like Wells Fargo (WFC, Fortune 500), some observers warn that banks aren’t socking away enough for a rainier day.

The disconnect is particularly acute in commercial real estate, where lenders are facing a surge of defaults on commercial mortgages and construction loans made when prices were much higher and demand for space much stronger.

Banks have been recognizing commercial real estate losses slowly, even though the high season for defaults isn’t expected to arrive until next year.

That’s not the only problem. Ill-defined or inconsistently applied rules for valuing securities and handling loan modifications can make it hard to say how healthy banks really are, from Citigroup (C, Fortune 500) and Bank of America (BAC, Fortune 500) on down.

The risk is that this year’s recovery could turn out to be a false dawn, delivering another blow to investor trust — not to mention people’s 401(k)s.

"The credibility of the banking system could take another step back," said Paul Miller, an analyst at FBR Capital Markets. "Everyone is expecting we’ve seen the peak in losses, but it’s impossible to know for sure because you can’t get an apples-to-apples comparison."

Extend, pretend?Banks have been swimming in losses since the collapse of the credit markets in mid-2007 sapped demand for all sorts of goods and services.

Loans written off as uncollectible hit their highest level on record in the second quarter, according to government data. Loan loss reserves are also at a peak since the government started keeping track in 1984, according to data from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

Taking losses on souring loans and troubled assets eats into profits, which tends to drive down share prices and executives’ pay. The losses also erode capital, reducing lendable funds and forcing banks to raise new money by selling stock or businesses.

Accordingly, banks have been eager to stretch their losses across as long a period as possible. Facing a triple-digit bank-failure count and trying to manage hundreds of troubled lenders, regulators are willing to go along, up to a point.

In April, accounting rule makers gave banks more leeway in valuing hard-to-trade securities. That’s led to current discussions over when banks will have to bring some off balance-sheet assets and liabilities back in house.

"Politically, this sort of forbearance is the lowest-cost way of stopping the train wreck," said Wayne Landsman, an accounting professor at the University of North Carolina. "The banks wanted that April change very badly, and you have to assume they wanted it for a reason."

Behind the curveThe risk, of course, is that deferring the reckoning can create a bigger problem later. And there are those who believe the banks are doing just that.

Nonperforming and restructured assets grew six times as fast as loan reserves over the past year, analysts at Keefe Bruyette & Woods estimate, while reserve building as a proportion of new troubled loans tapered off after peaking in the fourth quarter of 2008.

This pattern suggests "the banks are not ahead of the curve in providing for troubled loans," the KBW analysts wrote in a report earlier this month.

Plenty of trouble is ahead. Prices on apartment, industrial, office and warehouse properties dropped 33% over the past year, according to the Moody’s/REAL commercial property price index.

Real estate research firm Foresight Analytics estimates banks should have booked losses on around $110 billion of defaulted commercial real estate and construction loans. But so far they have taken their medicine in only about a third of those cases.

That means the banks could face a backlog of $70 billion or so defaulted but unreserved loans as we head into the teeth of down cycle in commercial real estate — where the bulk of bubble-era loans are due to be repaid or refinanced between 2010 and 2012.

Regional and community banks, rather than the giant TARP-taking entities, will bear the brunt of this onslaught. Banks with between $100 million and $10 billion in assets have almost $900 billion of commercial real estate exposure, Foresight estimates. That’s three times their capital.

"Right now, we’re closer to the beginning of this problem than the end," said Matthew Anderson, a partner at Foresight in Oakland, Calif.

Apples and orangesEven some seemingly well established positive trends look muddled with a closer look at the numbers.

For instance, publicly disclosed financial reports have been showing a slowdown in the growth of early-stage delinquencies, those in which borrowers are a month or two behind on their bills. Investors have been cheered by this trend because it suggests the worst losses are behind the banks.

But regulatory filings by the same banks often paint a less upbeat picture, said FBR’s Miller.

He said nonperforming asset levels were 17% higher in regulatory filings than in public statements, according to FBR estimates based on second-quarter data for the top 25 banks and thrifts by assets — suggesting that some big banks are understating problem loans as they go through the restructuring process.

One view into this puzzle is the banks’ handling of loan modifications and other changes, under the category of troubled debt restructurings.

Troubled debt restructurings have doubled over the past year, according to KBW, as banks extend loan maturities and cut interest rates or loan balances, particularly on troubled residential loans.

But not all institutions account for restructured loans in the same fashion — which could mean some bank investors are in for a surprise down the road as many restructured loans go sour.

"The issue is that accounting for loan mods is not transparent and makes delinquency data appear better on the surface," FBR’s Miller wrote in a note to clients this month.

"You Cheat, I Cheat, as Wall Street Acts as Model" (Bloomberg News commentary by columnist Susan Antila)

Trickle down really does work. Consider these inspired words, from an online reader of USA Today, reacting last week to news that Americans were lying, cheating and law-breaking to get their hands on an $8,000 tax credit for first-time homebuyers:

“The system is scamming you, so why not scam back a little,” wrote the reader, using the name “None in 08.” “You’ve seen what crooks in Washington and on Wall Street can get away with.” So “it’s time to get yours.”

Amen, brother. What are role models for, anyway?

People who make their livings studying the business world’s ethics — and lack thereof — say it doesn’t take a nutburger to sense there’s some systemic unfairness at work.

“The heavy hitters, the high-rollers and the powerful have been getting away with this type of thing, so people say, ‘Why shouldn’t I get my few cents?’” says Thomas Bausch, a professor of management who teaches business ethics at Marquette University in Milwaukee.

The public is onto the fact that the casino known as the stock market operates with one set of rules for the high rollers and another for the little people, says Barbara Porco, director of program development at Fordham University’s School of Business Administration, in New York City.

The truth is the public may have a better chance gambling at a casino than on Wall Street. At a casino, Porco said, “Whether it’s the five-dollar table or the thousand-dollar table, everyone plays by the same rules. That’s not how it works in the stock market, where you have different rules for different groups.”

Cue the Looters

Regrettably, the financial market casino of late has all the ambience of looters storming the neighborhood after natural disaster has struck.

Along with news that Joe Taxpayer had listed his 4-year-old as owner of the family home in hopes of pocketing that $8,000, we also learned in recent weeks that Citigroup Inc. is selling its Phibro LLC energy-trading unit to Occidental Petroleum Corp. for $250 million. Citi, recipient of $45 billion in taxpayer money, was highly motivated to slither out of the harsh spotlight associated with the $100 million bonus it owed to Andrew Hall, star Phibro trader. Thus, a $250 million corporate transaction was set into motion to protect one guy’s payday.

There is the possibility, of course, that decadence and thievery today is no worse than at other times in history, but I couldn’t find a lot of ethics pros willing to sign on to that thesis.

Titans and Progress

During the late 19th century, industrialists such as Andrew Carnegie and John D. Rockefeller lined their pockets by taking advantage of people. As Bausch notes, at least those meanies, unlike today’s financial titans, built something that lasted and had some economic value. Where’s the historian who’s ready to congratulate the team that cooked up today’s “dark pools”?

Porco sees the shift in the morality of business and political leaders reflected in feedback from her students.

For 20 years, the Fordham professor has started each semester by going around the classroom to ask students to identify their heroes. “When I first began at the university, I’d hear names of heroes who were corporate leaders, or heroes in the media or even in government,” she says. For the past four or five years, her students without exception have defaulted to naming members of their families. The hero of business or government is a dinosaur to the next generation.

So what happened that we got to this disheartening point? Stephen B. Young, global executive director at the St. Paul, Minnesota-based Caux Round Table, a group that’s taken on the unenviable task of promoting “a moral capitalism,” says the culture of indulgence and entitlement engendered by the baby boomers was one factor.

Bad Examples

There is also the simple matter of bad examples: The more people observe bad guys getting away with it, the more they cheat, says Dan Ariely, author of “Predictably Irrational: The Hidden Forces That Shape Our Decisions.”

Ariely worries about what he calls “the Madoff effect,” a swine-flu-grade virus that causes people who witness corruption to conclude that cheating has become acceptable, and to wind up cheating, too. When Mom and Dad are putting their tots’ names on the income-tax forms to scam $8,000, Ariely says, “we’re seeing the aftershock of all this dishonesty on Wall Street.”