Edward argues that, in a stunning and appalling end run around the Constitution (my words), the executive branch and the Fed have usurped Congress’s power to tax and spend–power dervived from the Constitution, an important part of our [once upon a time] checked-and-balanced political system. – Ilene

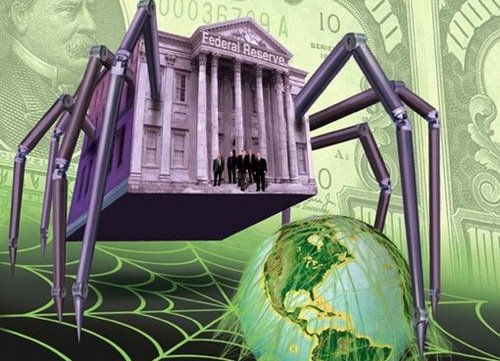

The creeping power grab by the executive branch and Federal Reserve

Courtesy Edward Harrison at Credit Writedowns

Courtesy Edward Harrison at Credit Writedowns

(written Nov. 3)

The power grab at the Federal Reserve is a topic I first broached back in February when the Federal Reserve was creating its alphabet soup of liquidity programs to pull us back from the brink of financial disaster. I was troubled about Fed policy then and I am still troubled today.

I am equally disturbed by what is happening in shift in the balance of power to the executive branch. The Obama Administration seems to be following in the footsteps of the Bush Administration and making its own power grab and Congress has only just begun to wake up to this and start to push back.

At the risk of making this post overly broad, I want to make a few general comments about how executive power in government operates before I take on the specifics of the cases at hand. Everyone who has studied political science is aware that dictators and oligarchies use crises to invoke fear that allows them to usurp power using the cloak of ‘national security’ as a Trojan horse to consolidate power.

I would argue, this is what has just happened in the U.S. post-9/11 and again after the Panic of 2008. I see these developments undermining Americans’ faith in the political process and I hope an appropriate restoration of the checks and balances laid out in the Constitution can be restored. Having made my editorial statement, let me move to the specifics.

Executive Branch power grab

In September, after Lehman Brothers failed, US Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson asked for and received a blank check to disburse $700 billion to former colleagues and rivals in the financial services industry as he and his staff saw fit. In a brilliant act of cunning, Paulson had gotten approval to do anything he wanted from a gutless Congress more interested in loading the bill with sweeteners. This bill was not unlike the Patriot Act, passed after the 9/11 attacks, in that it increased the executive branch’s ability to intervene in the economy as they saw fit. I called it the Economic Patriot Act.

Originally, the Economic Patriot Act was about marking to market. However, once Gordon Brown started recapitalising Britain, Paulson made an about-face and proceeded to dispense the money in a similar fashion (albeit with much fewer strings attached than in the UK).

When the Obama Administration came to town, the modus operandi were not much different. Other support programs were forthcoming and bailouts at Citi and BofA ensued.

With the economy and banks on sounder footing and much of the money returned to taxpayers, the Obama Administration has turned to regulatory reform – and, what do you know – they are looking for a blank check again to do as they please in resolving too big to fail institutions that run into trouble. Again, as with Bush in 2002, if Congress gives the executive branch any blanket authority, it will be used and Congress will be cut out of the process. This is NOT how the American system of government is supposed to be run.

The Fed is grasping for the brass ring too

Enter the Federal Reserve. The Fed has been engaged in a policy of acting in concert with the Executive Branch in a non-arms length fashion since this crisis began. All of the liquidity programs and backstops the Fed has implemented are not just about liquidity, they are subsidies that lower the cost of capital and increase profits in the banking sector. As such, these subsidies are actually a part of America’s fiscal policy – stimulus, if you will. It is a clear no-no for the Federal Reserve to inject itself into fiscal matters. And to top it off, the Fed is refusing to be transparent about the process. Why would we make it the Systemic Risk Regulator?

Willem Buiter says it best so I will just quote him verbatim from his article, “Should central banks be quasi-fiscal actors?”:

Any action going beyond that, such as the recapitalisation of insolvent banks through quasi-fiscal subsidies, ought to be funded by the Treasury. The central bank should be involved only as an agent of the Treasury – an expert assistant. It should not put its own conventional or comprehensive balance sheet at risk.

The two arguments against the central bank acting as a quasi-fiscal agent are, first, that acting as a quasi-fiscal agent may impair the central bank’s ability to fulfil its macroeconomic stability mandate and, second, that it obscures responsibility and impedes accountability for what are in substance fiscal transfers. In the US such actions subvert the Constitution, which clearly states in Section 8, Clause 1, that the power to tax and spend rests with the Congress: “The Congress shall have Power to lay and collect Taxes, Duties, Imposts and Excises, to pay the Debts and provide for the common Defence and general Welfare of the United States; but all Duties, Imposts and Excises shall be uniform throughout the United States.”.

If, as happened in the USA on a vast scale, the central bank allows itself to be used as an off-budget and off-balance-sheet special purpose vehicle of the Treasury, and refuses to provide to the Congress some of the information essential for the quantification of the fiscal transfers it has made, the central bank not only subverts the constitution. By attempting to hide contingent commitments and to disguise de-facto subsidies by not divulging relevant information on the terms on which the central bank has offered financial assistance, it undermines its own independence and legitimacy and impairs political accountability for the use of public funds – ‘tax payers’ money’. It is surprising that a country whose creation folklore attributes considerable significance to the principle of ‘no taxation without representation’ would have condoned without much outcry such a blatant violation of the equally important principle of ‘no use of public funds without accountability’. This indeed amounts to a quiet usurpation of the power of the legislature by the central bank.

Qualitative easing, or whatever you call it, must end. With the FOMC starting its two-day meeting tomorrow, and with the Reserve Bank of Australia having already hiked twice, it will be interesting to see if the Fed retracts its “extended period” language as many of us expect. While I think it premature in regards to the robustness of the economy, the Fed needs to show it is an independent actor.

Once lost, independence will not be easily restored.