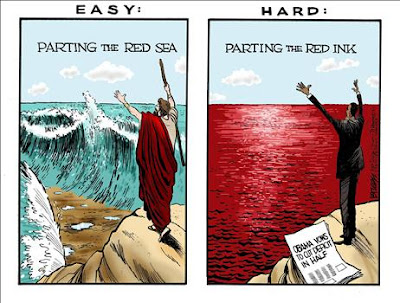

A Tsunami of Red Ink

Courtesy of Michael Panzner at Financial Armageddon

Courtesy of Michael Panzner at Financial Armageddon

Just over a week ago, Bloomberg revealed in "Geithner Says Commercial Real Estate Woes Won’t Spark Crisis," that the U.S. Treasury Secretary did not appear to be overly concerned about the threat posed by brewing problems in the commercial property sector:

U.S. Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner said commercial real estate woes won’t set off a new banking crisis, in remarks to the Economic Club of Chicago.

“I don’t think so,” Geithner said, when asked whether commercial real estate could set off another banking meltdown. “That’s a problem the economy can manage through even though it’s going to be still exceptionally difficult.”

The global economy has accelerated since the worst of the recession and banking crisis last year, Geithner said, noting a U.S. Commerce Department report today showing the economy expanded 3.5 percent in the third quarter.

“You can say now with confidence that the financial system is stable, the economy is stabilized,” Geithner said. “You can see the first signs of growth here and around the world.”

Is he serious? All you have to do is spend about 15 minutes reading through just a few of the reports that were published recently and it quickly becomes apparent that a tsunami of red ink is forming in the sector, ready to come crashing down on the whole of the banking sector — as well as the economy — in the immediate period ahead:

"Why This Real Estate Bust Is Different" (BusinessWeek)

Unrealistic assumptions, layers of investors, sky-high prices, and possible fraud will make it hard to clean up the mess in commercial real estate

When Goldman Sachs (GS) sold complex bonds backed by the Arizona Grand Resort and other commercial properties in 2006, it suggested the returns would be strong. The 164-acre luxury Arizona Grand, set against the Sonoran Desert in Phoenix, boasted an award-winning golf course, deluxe spa, and several swank restaurants. The on-site water park was named one of the best in the country by the Travel Channel. With the resort’s new owners planning to refurbish hotel rooms and common areas, Goldman told investors that the renovations would help boost cash flow.

As was so often the case during the real estate boom, the lofty projections didn’t pan out. When the economy softened and business travel slumped, Arizona Grand’s bookings slipped to 67%, from 80%. The resort defaulted on the $190 million underlying loan in 2009—a hit that alone could largely wipe out investors who bought the riskier pieces of the Goldman mortgage-backed securities deal.

"It’s one of the largest losses we have forecasted for an individual loan," says Steve Kuritz, a senior vice-president at Realpoint, an independent credit-rating agency. The property, once valued at $246 million, is now worth just $93 million. A spokesman for Goldman says the pricing on the bonds was in line with market levels at the time and not above what investors could get on similar securities. Grossman Co. Properties, which owns Arizona Grand, didn’t return calls for comment.

It would be easy to write off this blowup as just another casualty in the regular boom-and-bust cycle of the $6.4 trillion commercial real estate market. But the Goldman deal, with its unrealistic assumptions, multiple layers of investors, and stratospheric prices, helps illustrate why this downturn is more complicated than previous ones—and will turn out to be far costlier. Already, prices have plunged 41% from the peak in 2007, according to Moody’s/REAL Commercial Property Price Index—worse than the 30.5% fall in the housing market from its 2006 apex. "We’ve never seen this extreme a correction as far back as the data go, which is the late 1960s," says Neal Elkin, president of Real Estate Analytics, the research firm that created the index. Adds billionaire investor Wilbur Ross: "Commercial real estate has gone from being highly liquid at sky-high prices to being extremely illiquid at distressed prices."

To appreciate why this bust is like no other, first consider the typical commercial real estate downturns that used to crop up every 5 or 10 years. The pattern was predictable: When prices for apartment complexes, office buildings, shopping malls, and other properties began to rise, developers sped up their projects to cash in on the bull market. Eventually, some of those developers, unable to fill all the new space, began to default on their loans, and lenders were stuck with the buildings they’d financed. The slump lasted no longer than the time it took for the property glut to be worked down.

TURNING A BLIND EYE

But overbuilding isn’t the culprit in this bust. An oversupply of money is what pushed commercial real estate over the edge.It turns out the same excesses that drove the housing market’s crazy rise and fall were present in commercial real estate, too—but they have largely gone unnoticed until now. Bankers, in their haste to make more and bigger loans, blindly accepted borrowers’ wildest growth assumptions and readily overlooked other shortcomings on loan applications. They did so in part because they could easily sell their dubious loans to investors in the form of commercial mortgage-backed securities. As the market overheated, it became a breeding ground for fraud: A flurry of new court cases reveals the disturbing extent to which commercial mortgage borrowers may have doctored loan documents.

While the housing crisis seems to be easing, the commercial storm is still gathering strength. Between now and 2012, more than $1.4 trillion worth of commercial real estate loans will come due, according to real estate investment firm ING Clarion Partners. Analysts at Deutsche Bank (DB) estimate that borrowers will have trouble rolling over as many as three-quarters of the loans they took out in 2007, the most toxic vintage.

For the banks and investors whose money fuels the economy, this presents major problems. Their losses will likely cast a shadow over lending—and, by extension, the overall economy—for years. The market won’t fully recover until 2020, says Kenneth P. Riggs Jr., CEO of Real Estate Research, and in cases where "values were over the top…maybe never."

In the short term, toxic securities are creating a new problem weighing on the market: a tangle of interconnected investors fighting over the remains of the properties they own. In the past the damage was limited to a handful of lenders who invested directly in any given project. Now there can be dozens of groups of investors, each with its own agenda. The April bankruptcy of shopping mall owner General Growth, one of the largest real-estate-related bankruptcies ever, affected hundreds of parties—an unprecedented slicing and dicing of assets. These investors won’t soon forget the bust and aren’t likely to get back into the market as aggressively as they once did.

And yet the securities are only a secondary problem. The main driver of the commercial real estate bust is the underlying loans. How frothy did the market get? In one notable example, New York investment fund Sterling American Property and real estate company Hines paid $281 million in 2007 for the 42-floor office building at 333 Bush St. in San Francisco. That worked out to $518 a square foot, far higher than today’s price, according to Real Capital Analytics, a research firm. Less than two years later, the building’s primary tenant, law firm Heller Ehrman, filed for bankruptcy and stopped making rent payments. According to Real Capital Analytics, the building’s owners did not make a recent loan payment, and the lender is expected to begin foreclosure proceedings. Says a spokesman for Sterling and Hines: "[We] continue to own and operate the property."

What’s striking is how quickly some big commercial deals have gone south. In April 2007, Charney FPG, a New York real estate partnership, paid about $180 million to buy a 22-story office building in Manhattan’s Times Square district. It borrowed $202 million to pay for the purchase, renovations, and incidentals—111% financing. Because the rental income didn’t cover the debt payments, Comfort’s lenders, Wachovia and RBS Greenwich Capital, required the firm to set aside $10 million in reserves to keep the project afloat until it got more paying tenants. Those occupants never materialized, and by July the owners had exhausted 95% of their reserves. The building is now in jeopardy of being seized by the bankers, says Real Capital Analytics’ head of research, Dan Fasulo. "Everyone knows Judgment Day is coming." Says a Charney spokesman: "The owners are in the midst of restructuring the debt." Wachovia and RBS declined to comment.

Commercial lending mirrored mortgage lending in another way: Loans were made based on an unshakable belief that the market would never go down. An analysis by research firm REIS of mortgage securities created between 2005 and 2008 found that income projections for properties exceeded their historical performances by an average of 15%. "It was all based on assumption of cash flow," says Howard S. Landsberg of New York-based consultant Weiser Realty Advisors. "If you couldn’t afford to pay the bank back now, in three years you could count on another $20 a square foot" in rent. When the numbers didn’t add up, some lenders got imaginative. Says a banker at a large Wall Street firm: "If the cash flow wasn’t there, you had to ignore it or find ways to create it."

"Gloomy Times for Commercial Real Estate" (San Francisco Chronicle)

Shopping centers, office buildings, industrial spaces, hotels and apartments can expect a period of "enveloping gloom" from the recession and credit crunch, according to a report released on Thursday.

Values will plunge, vacancies will rise and rents will decrease across all types of commercial property before the market hits bottom in 2010, according to the "Emerging Trends in Real Estate" forecast from the Urban Land Institute and PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP.

Based on interviews with 900 industry leaders, including investors, developers and financiers, the report was released at an Urban Land Institute conference for developers, planners and other real estate professionals taking place this week at San Francisco’s Moscone Center.

No quick recovery is in store, the report said. "2010 looks like an unavoidable bloodbath for a multitude of ‘zombie’ borrowers, investors and lenders," it said. "The shake-out period may extend several years as even some conservative owners with well-underwritten loans from the early 2000s see their equity destroyed."

"$500 Billion Of Commercial Real Estate To Mature Soon" (The Atlantic Business Channel)

There was a Congressional subcommittee hearing today — in Atlanta. The House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform’s Domestic Policy Subcommittee addressed the residential and commercial real estate market in the Georgia metropolis. Sadly, the meeting was not on C-SPAN, but I managed to skim through some of the prepared remarks by more than a dozen witnesses from judges to economists to bankers. I was particularly interested to hear what those testifying had to say about commercial real estate, as I think that market will be one of the big business stories of 2010.

Atlanta has been gravely damaged by the housing bubble’s pop. As a result, it sort of makes sense that only one witness appears to have spent much time addressing commercial real estate. Luckily, it was Jon Greenlee, Associate Director, of Banking Supervision and Regulation at the Federal Reserve. So it’s pretty high quality testimony.

His analysis is also rather broad, not focusing on Atlanta’s commercial real estate as much as the bigger picture. His prepared remarks make one thing utterly clear: the Fed is keeping a very close eye on commercial real estate (CRE). And it’s worried. CRE is a big market to watch. Greenlee notes that at the end of the second quarter, commercial real estate debt was approximately $3.5 trillion.

And here comes the bad news:

Also at the end of the second quarter, about 9 percent of CRE loans in bank portfolios were considered delinquent, almost double the level of a year earlier. Loan performance problems were the most striking for construction and development loans, especially for those that financed residential development. More than 16 percent of all construction and development loans were considered delinquent at the end of the second quarter.

I

t should be a really, really worrying statistic that 9% of all CRE loans are delinquent — because it isn’t that hard for most of these loans to make monthly payments. Commercial mortgages are generally structured differently from fixed-rate residential mortgages. Many require relatively low monthly payments for the term of the loan, with a larger balloon payment due upon the loans’ maturity. So if a large portion of commercial borrowers can’t even make those relatively easier monthly payments, then we’ll see some far more serious problems once those balloons come due.

And that storm is coming. Greenlee also says:

Of particular concern, almost $500 billion of CRE loans will mature during each of the next few years.

$500 billion isn’t a small number by anyone’s standards. Don’t expect these loans to be rolled over very easily either. Banks are still keeping clenching their wallets tightly, and the commercial mortgage-backed securities market remains largely closed. Speaking of CMBS, banks have a lot of it, and those delinquencies are increasing as well, says Greenlee.

"Fitch Conference: Commercial Real Estate Decline & Negative Credit Effects; Muni Market Downturn" (BusinessWire)

Fitch Ratings will host its annual Morning Credit Brief Conference on Tuesday, Nov. 17, 2009 at the Grand Hyatt in midtown Manhattan with a focus on the broad credit implications for the collapsing commercial real estate market.

The performance metrics of commercial real estate (CRE), an area with a significant risk exposure for financial institutions and the structured finance market, continues to deteriorate at an unprecedented pace. While CRE loans, excluding the more problematic construction and development portfolios, represent more than 125% of total equity for the 20 largest banks rated by Fitch, the risk is even higher for banks with less than $20 billion in assets, as average CRE exposure represents more than 200% of total equity for these institutions. The negative credit implications of the declining CRE market are widespread, affecting not only large and regional financial institutions, but also CMBS entities, insurance companies and REITs whose investment portfolios are seeing a sharp decline in value due to their exposure to falling real estate prices.

"U.S. Shops and Apartments Head for Record Vacancies" (Bloomberg)

Stores, apartment buildings and warehouses in the U.S. will set new vacancy records before a recovery takes hold in the job and commercial property markets, according to a forecast by CB Richard Ellis Group Inc.

Vacancies at industrial properties will climb to almost 16 percent in 2011 and apartment vacancies will top out at 8.1 percent this quarter, CBRE chief economist Ray Torto said in a presentation at the Urban Land Institute convention in San Francisco. The proportion of empty space at shopping centers and malls will increase to about 13 percent in 2010, he said.

U.S. commercial real estate prices have plunged almost 41 percent since October 2007, the Moody’s/REAL Commercial Property Price Indices show. The highest unemployment since 1983 has lowered demand for office and retail space and reduced consumer confidence and spending. Job cuts are also prompting tenants to move out of apartments.

“We don’t have a sustainable recovery yet,” Kenneth Rosen, a University of California economist, said in a panel discussion with Torto. “The problem is not supply, but how we get demand back.”

U.S. office vacancies are forecast to reach 18.6 percent in the first quarter of 2011, just shy of 1991’s 19.1 percent record, Torto said.

“Increasingly, investors are viewing office as a kind of non-core investment, which is a concern,” said Jonathan D. Miller, author of PricewaterhouseCoopers’s “Emerging Trends in Real Estate” report, released today. “Tenants come and go, and with these cyclical swings, it can be a troublesome investment if you don’t time it right.”

"Commercial Property ‘Long Way’ From Rebound, GE’s Pressman Says" (Bloomberg)

The U.S. commercial property market is far from recovery and needs job growth, sustained low interest rates and further government support, said GE Capital Real Estate Chief Executive Officer Ronald Pressman.

“We’re a long way from where we’d like to be,” Pressman said at the Urban Land Institute’s annual meeting in San Francisco yesterday. “The stakes are very big here.”

Defaults and late payments on property loans sold as commercial mortgage-backed securities jumped more than fivefold to 4.52 percent of the total in the third quarter from a year earlier, New York-based real estate researcher Reis Inc. said. About $26.6 billion of CMBS loans were 60 days or more past due.

Commercial real estate won’t stop falling for 18 to 24 months after the economy bottoms out, as the full effect of the recession hits landlords, Pressman said in an interview at the San Francisco event. The unemployment rate needs to drop to 5 percent to 6 percent before the property market rebounds, according to his presentation. Joblessness rose to 9.8 percent in September, the highest since 1983.

About $22 billion worth of transactions will be completed this year, or 5 percent of the 2007 market peak, Roy March, CEO of commercial brokerage Eastdil Secured, said at the same event. Deals are down 74 percent from 2008 for offices, 72 percent for apartment buildings and 60 percent for retail properties, he said.

Stores, apartment buildings and warehouses in the U.S. will set vacancy records before a recovery takes hold, according to a forecast by CB Richard Ellis Group Inc. Office vacancies will fall just short of the record set in 1991, it said.

And to make matters worse, the agency that oversees much of the bank sector has decided, as the Dayton Business Journal reports in "FDIC Makes Statement on Commercial Real Estate Workouts," that the way to deal with the problem is to encourage lenders to rely on a dangerously flawed approach that is nonetheless all the rage nowadays: pretend and extend.

The Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. adopted a policy statement supporting prudent commercial real estate loan workouts, it reported Tuesday.

FDIC’s statement emphasizes performing loans, including those that have been renewed or restructured on reasonable modified terms, made to creditworthy borrowers will not be subject to adverse classification solely because the value of the underlying collateral declined.

The policy statement gives guidance to examiners and financial institutions that are working with commercial real estate borrowers who are experiencing diminished operating cash flows, depreciated collateral values, or prolonged delays in selling or renting commercial properties, the FDIC said.

Agencies of the Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council said prudent loan workouts are often in the best interest of both financial institutions and borrowers, particularly during difficult economic conditions. Financial institutions that implement prudent loan workout arrangements after performing comprehensive reviews of borrowers’ financial conditions will not be subject to criticism for those efforts, even if the restructured loans have weaknesses that result in adverse credit classifications, the FDIC said.