AIG: Collusion Of Epic Proportions Between Goldman’s US Treasury Branch And Goldman Sachs

Courtesy of Tyler Durden

Must read piece from David Fiderer, first published on Huffington Post

How Paulson’s People Colluded With Goldman To Destroy AIG And Get A Backdoor Bailout

Too Big To Fail is revelatory, though not in the way Andrew Ross Sorkin intended. The book offers startling evidence that Hank Paulson and his deputies colluded with Goldman to create a liquidity crisis at AIG, and to manipulate the government funding a backdoor bailout of AIG’s CDO counterparties, most notably Goldman. It’s not that Sorkin’s sources recounted the truth. Quite the opposite. Rather, they told him stories that were so transparently dishonest that the truth emerges by way of negative implication.

To understand what happened, you need to remember that the top guys at Goldman are really, really smart. They are like champion chess players who anticipate the possible moves of their opponent. The guys at Goldman can quickly grasp how pieces of a financial transaction work together, like the pieces on a chessboard, to game out different scenarios. This attribute is not unique to the guys at Goldman; it’s an essential quality of every good banker. But it does mean that the guys at Goldman cannot credibly profess to being oblivious.

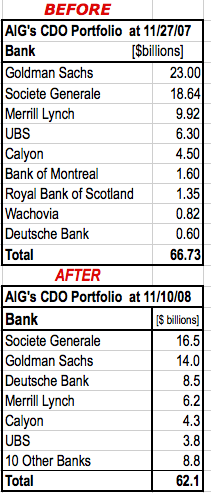

The other thing that you must remember is that the dagger hanging over AIG and Goldman — the eventual payout to the CDO counterparties — was a zero-sum game between the two financial giants. On June 30, 2008, AIG’s net worth was $79 billion and its CDO obligations totaled $62 billion. On August 27, 2008 Goldman’s net worth was $42 billion and its share of the infamous CDO portfolio was $22 billion. The stakes were huge.

Also, none of the critical elements that led to AIG’s demise were obscure. In retrospect they seem quite obvious. Unfortunately, few in the financial media have attempted to understand those critical elements.

Before we get to the liquidity crisis at AIG, we need to go back to that special relationship between Goldman and AIG…

Goldman bought credit protection exclusively from AIG because:

Like its peers, Goldman underwrote billions of dollars of toxic securities known as subprime collateralized debt objections, or CDOs, and simultaneously bought credit protection on those CDOs in the form of credit default swaps. But Goldman was unique in that it only bought protection from AIG Financial Products, or AIGFP, and no one else. Under normal standards of risk management, this approach is imprudent; a bank should diversify its risk exposures whenever it can. Given that AIG was Goldman’s biggest client, and that the CDO exposure at AIG was a huge part of Goldman’s equity base, it’s inconceivable that Hank Paulson, Goldman’s CEO until June 2006, would not have been regularly briefed on this matter. The same goes for Goldman’s board of directors. It’s a very basic and essential part of any bank’s risk management and corporate governance.

It’s also a basic tenet of risk management to game out the different scenarios under which Goldman might seek recovery under its credit default swaps. Based on that analysis, the choice to deal exclusively AIG, in retrospect, seems very obvious, for four reasons set forth below.

1) AIG Financial Products was not regulated, whereas the monolines were;

This is one of those really basic things that few in the media seems to grasp. The other large companies offering credit protection on the CDOs were the monoline insurance companies, names like MBIA or AMBAC. AIGFP was not regulated, whereas the monolines were. A regulator can order an insurer to withhold any payout that might impair that company’s ability to service its other policyholders. That’s precisely what the New York State Insurance Department did last April, when it ordered Syncora, the monoline formerly known as XL Capital Assurance, to suspend payments. This state’s regulatory authority to interfere with the terms of a contract proved to be a powerful hammer. It incentivized the CDO banks to negotiate haircuts on their claims throughout 2008.

A lot of people compare the settlements with the monolines with those at AIGFP and wonder why the monolines negotiated better deals. But in fact, they are comparing apples and oranges. The only government entity legally authorized to interfere with AIGFP’s contracts was a bankruptcy court. But even that authority had been seriously curtailed.

2) AIGFP was willing to post cash collateral, which was outside the grasp of a bankruptcy judge;

Here’s another very basic thing. The credit protection sold by the monolines included financial guarantees as well as credit default swaps, whereas AIGFP extended only credit default swaps. A credit default swap is a financial derivative. One of the common, and insidious, attributes of financial derivatives is that a counterparty may need to post margin, or cash collateral, whenever the spot value of its contractual claim turns negative. Here’s an overly simple example: Suppose AIG promised to sell Goldman one barrel of oil on January 25, 2011 for $80, and then on June 25, 2010 spot price is $100 (i.e. an implicit $20 loss). AIG would post $20 in collateral with Goldman. If the spot price falls to $65 on July 25, then AIG would get its $20 collateral returned, and also receive $15 in collateral deposited by Goldman.

As a rule the monolines were unwilling to sign any contract that required them to post collateral. They accrue insurance reserves and, again, insurance regulation is predicated on the idea that one policyholder ’s recovery not should leapfrog ahead of all the others. But that’s precisely the idea behind posting collateral on a derivative. If AIGFP filed for bankruptcy, Goldman would be entitled to immediately liquidate the credit default swap and permanently keep its cash collateral; a bankruptcy judge could not touch it. The recently amended bankruptcy code clarified the special priority given to derivative counterparties over other creditors.

So, as you would expect, It wasn’t simply the support of the regulators that gave the monolines the upper hand in negotiating with the CDO counterparties; it was also the fact they they held the cash.

3) AIGFP would have been wiped out by a bankruptcy filing, because it was active in financial trading;

There’s another reason why the monolines had the upper hand, whereas AIGFP did not. Bankruptcy was always a viable option for the monolines, whereas it was not for AIGFP. Aside from its book of business providing credit support for CDOs, AIGFP was very active in all sorts of financial trading of all sorts of derivatives. The monolines were not really involved in that business.

The vast bulk of business done by financial traders is hedged, meaning there are always two back-to-back contracts. Another overly simple example: If AIG promised to sell Goldman one barrel of oil on January 25, 2011 for $80, AIG would simultaneously contract with Morgan Stanley to buy one barrel of oil on January 25, 2011 for $78, and lock in the $2 profit. Throughout the next 12 months, any profit from one contract would correspond to the loss on the other. But if AIG filed for bankruptcy on June 25, 2010, Goldman could choose to liquidate its contract and hold on to its collateral, whereas Morgan Stanley might still insist of selling the oil on the later delivery date. The hedge would then become unwound, and suddenly expose AIG to a huge trading loss.

The preferential treatment given to derivatives subverts the entire purpose of a bankruptcy filing, which is to buy time for an orderly restructuring. For AIGFP, the downside risk of a bankruptcy filing was vast and unknown, which was not the case for the monolines.

Because Goldman is very savvy about trading risk, it must have mapped out an endgame enabling it to declare “checkmate” once AIG were backed into a corner.

4) AIG did not understand what it was doing; it relied on the rating agencies.

But if Goldman was so smart, how could AIG be so dumb? There’s a short answer and a long answer. The short answer is three little letters: AAA. The long answer gets to the same result; it just takes a longer while to get there.

According to Michael Lewis’s reporting in Vanity Fair, the guys at AIGFP were clueless:

Toward the end of 2005, Cassano [the head of AIGFP] promoted Al Frost, then went looking for someone to replace him as the ambassador to Wall Street’s subprime-mortgage-bond desks. As a smart quant who understood abstruse securities, Gene Park was a likely candidate. That’s when Park decided to examine more closely the loans that A.I.G. F.P. had insured. He suspected Joe Cassano didn’t understand what he had done, but even so Park was shocked by the magnitude of the misunderstanding: these piles of consumer loans were now 95 percent U.S. subprime mortgages. Park then conducted a little survey, asking the people around A.I.G. F.P. most directly involved in insuring them how much subprime was in them. He asked Gary Gorton, a Yale professor who had helped build the model Cassano used to price the credit-default swaps. Gorton guessed that the piles were no more than 10 percent subprime. He asked a risk analyst in London, who guessed 20 percent. He asked Al Frost, who had no clue, but then, his job was to sell, not to trade. “None of them knew,” says one trader. Which sounds, in retrospect, incredible. But an entire financial system was premised on their not knowing–and paying them for their talent! [Emphasis added.]

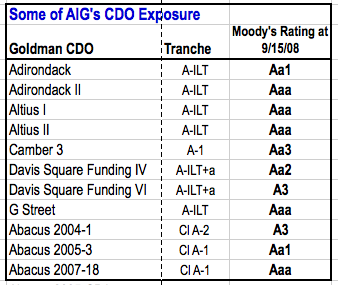

It seems less shocking if you understand how these CDOs were put together and sold. Take a few minutes and glance over the prospectus for Davis Square Funding VI, one of the dozens of CDOs structured by Goldman before the risk was laid off on AIG. You could spend all day studying the document, but you will never be able to answer the question, “What am I buying?” The document doesn’t tell you. That’s the point. It’s evident in every aspect of this document and the offering circulars for most of the other CDOs. The business purpose, the essence of the deal, can be summarized in one word: obfuscation.

Goldman argued that these CDOs were put together to meet market demand, but demand for what? These subprime CDOs were not financing anything (the underlying mortgages and mortgage securities had already been financed), nor were they promoting liquidity in the marketplace (they couldn’t be traded because nobody knew what was in them).

If you wanted to invest in a diversified pool of subprime mortgages, there was no reason to waste hours and hours studying the impenetrable documentation of a CDO. Instead, you could look into any subprime mortgage deal, like MASTR Asset Backed Securities Trust 2005-NC2. Skim the prospectus for five minutes, and you know that the deal is comprised of 3,380 subprime mortgages, all of which were originated by New Century Financial, 55% of which were in California, 100% of which are interest only, 60% of which closed with second liens, 58% of which relied on “stated documentation,” and 83% of which had prepayment penalties. If you don’t like MASTR 2005-NC2, you can easily compare it with hundreds of other stellar transactions.

Remember, AIGFP only assumed risk exposure on the “super senior” classes, or tranches, of these CDOs. They only assumed the risk on paper that was rated AAA. Therein lies the faulty assumption that AIG and almost everyone else made before they ever started slogging through the impenetrable documentation. It’s rated AAA so you don’t need to worry about the details. The offering circular for Davis Square Funding VI is just like the offering circular for Davis Square Funding VII and countless other CDOs. It tells you Moody’s Expected Loss Rate on a credit rated AAA. After 20 years, the cumulative loss is 0.02 percent. It doesn’t tell you that the deal was structured to make a sham of the due diligence process.

People who bought these CDOs looked at the ratings and almost nothing else. They relied on Goldman and the rating agencies to make sure that everything was OK.

Which again brings us to the issue of posting collateral. As a matter of policy, financial institutions rated AAA or AA almost never agree to post collateral on their derivative trades. (That’s one reason why big banks find trading to be so profitable.) The only reason why the guys at AIGFP would have ever agreed to post collateral back in 2005 or 2006 is because they thought there was no way in hell that these CDO tranches rated AAA would never be valued at anything below par.

But Goldman’s credit default swaps would not trigger a bankruptcy, because there was no way to figure out their market value.

Goldman started harassing AIGFP to start posting cash collateral as early as August 2007, when the matter went to the “highest levels” at Goldman Sachs.

But Goldman met with limited success, for obvious reasons. The idea that these CDOs could be marked to market is a joke. There never was any real market of buyers and sellers of these things. AIG’s auditor,PricewaterhouseCoopers, and the Fed’s auditor, Delloite & Touche, determined under fair value accounting rules that there was no way that the CDO obligations could be valued according to any market benchmark.

AIG and Goldman had spirited talks over the amount of posted collateral for over a year, but those talks had remained at an impasse. No one could agree on the CDOs’ “market value.” So long as AIG was solvent, the inability to quickly ascertain the CDOs’ value worked in AIG’s favor. Later, when AIG faced a liquidity crisis, the inability to quickly ascertain the CDOs’ value worked against AIG.

Various side deals mask the true magnitude of Goldman’s participation in AIG’s CDO portfolio.

According to the AIG memo on CDO exposures, dated November 27, 2007, obtained by CBS News, Goldman’s CDOs represented about a third of the $67 billion total. But that may have been understating Goldman’s role in building up the portfolio. About 16 of Societe Generale’s trading positions were for CDOs that were arranged by Goldman. Apparently, one way that Goldman would offload CDOs would be to sell them, along with credit protection from AIG, as a package deal. In other words, some of the banks never seriously intended to hold the CDOs in the first place. But Goldman used them as a front for its own syndicating efforts.

Later, around the time Tim Geithner was brought in to settle the CDO matter, Goldman pulled another stunt to make it appear as if its CDO exposure to AIG was smaller than it actually was. The transaction is alluded to in a couple of obfuscatory paragraphs (pages 16 and 17) in Neil Barofsky’s SIGTARP report on the AIG bailouts. It appears as if Goldman suddenly sold $8 billion in CDOs to Deutsche Bank, so that it would appear as if Goldman’s share of the total would look smaller. But the only way that Deutsche Bank would have bought the stuff is if there were no risk involved.

On September 15, 2008, the rating agencies thought that AIG’s CDO portfolio looked just fine.

The Washington Post printed a 2,700-word article about AIG’s internal e-mails during 2007, when the guys at AIGFP kept insisting that the CDOs did not present any kind of troublesome risk. But the Post left out a critical element in the narrative. At that time, virtually all of the 148 CDO trades, listed in a November 27, 2007 memo obtained by CBS, were still rated AAA.

In fact, most of these CDOs were first downgraded in May 2008, the same month that AIG was downgraded from Aa2 to Aa3. At the time, the CDO downgrades were fairly insignificant. Of course we don’t know why the CDO downgrades occurred when they did, because we don’t really know what’s inside of them. But consider how bad the damage was by May 2008. Among the subprime bonds that comprised the ABX 2006-1index, the average foreclosure rate was already 25%.

Was AIG really too big to fail? Maybe if you worked for Goldman.

The party line, expressed in Too Big To Fail and elsewhere, is that an AIG bankruptcy posed a greater systemic risk than a Lehman bankruptcy, because AIG was so much bigger. But that analysis is highly superficial and very misleading. AIG itself was a holding company, which guaranteed the debt of its unregulated financial subsidiary, AIGFP. The lion’s share of AIG’s revenues and profits, and about 80% of its consolidated assets, were concentrated among its different insurance company subsidiaries. Those insurance companies were solvent. They did not pose any systemic risk. In fact, it’s quite likely that they would have continued to operate outside of bankruptcy.

The only subsidiary with major problems was AIGFP, whose financial obligations were guaranteed by the parent. But AIGFP was only about one-third the size of Lehman. It’s almost impossible to see how AIGFP ever posed a systemic risk, unless everyone’s intention to provide a backdoor bailout to the banks. Put another way, it seems that the only reason that the government needed to step in for AIG was to provide a backdoor bailout to its banks.

Goldman’s scheme to create a liquidity crisis at AIG, in order to manipulate the government into paying CDO counterparties 100 cents on the dollar

Because of laws that emasculated regulatory oversight, Goldman’s trading positions in credit derivatives with AIG had escaped the scrutiny of the Fed until September 11 or 12, 2008, when AIG told the New York Fed that it would soon run out of cash. The CDOs did not trigger a liquidity crisis at AIG, at least, not directly. Rather, it was the imminent cash drain from anticipated downgrades, from AA- to A-, which would trigger $30 billion in new collateral postings on AIGFP’s trading positions. In addition, someone at the company had screwed up. They had invested billions in cash collateral, intended for someone else, in highly rated mortgage securities, for which there was suddenly no liquid market. So AIG needed to come up with the cash right away.

Simultaneously, of course, Lehman Brothers was imploring the government for support, and Paulson’s position, at least on September 12, 2008, was that the Federal government would provide no support of any kind to bail out a private company like Lehman or AIG. Private bankers must come up with a private solution on their own.

On September 15, 2008, the same morning that Lehman’s bankruptcy sent shockwaves, Geithner had convened a meeting with JPMorgan Chase and Goldman to work on an emergency bridge financing for AIG. Why include Goldman? Traditionally, the bank with the largest credit exposure to distressed borrower helps arrange the debt restructuring. Geithner opened the meeting, and left soon thereafter, leaving Paulson’s deputy, Dan Jester, in charge. Jester was a former Goldman banker whom Paulson had plucked in July 2008 to work on matters that concerned Paulson.

September 15, 2008: Paulson’s deputy sabotages efforts to negotiate a private bank deal.

Sorkin describes the opening of the Monday morning meeting:

“Look, we’d like to see if it’s possible to find a private-sector solution,” Geithner said addressing the group. “What do we need to do to make this happen?”For the next ten minutes the meeting turned into a cacophony of competing voices as the banks tossed out their suggestions: Can we get the rating agencies to hold off on the downgrade? Can we get other state regulators of AIG’s insurance subsidiaries to allow the firm to use those assets as collateral?

Geithner soon got up to leave, saying, “I’ll leave you with Dan,” and pointed to Jester, who was Hank Paulson’s eyes and ears on the ground. “I want a status report as soon as you come up with a plan.”

A critical point here is that Pauslon’s deputy, not Geithner, sat at the table to lead government negotiations.

Job 1 was to persuade the rating agencies to forestall their anticipated downgrades, which would have burned up billions because of increased calls to post collateral. This task was assigned to the government’s representative, Dan Jester.

“He was as useless as tits on a bull.” [AIG CEO] Bill Willumstad, normally a calm man, was in an uncharacteristic rage as he railed about Dan Jester of Treasury, while telling Jamie Gamble[a lawyer at Simpson Thatcher] and Michael Wiseman [a lawyer at Sullivan & Cromwell] about his and Jester’s call to Moody’s to try to persuade them to hold off on downgrading AIG.Willlumstad had hoped that Jester, using the authority of the government and his powers of persuasion as a former banker, would have been able to finesse the task easily.

Willumstad explained that the original plan “was that the Fed was going to try to intimidate these guys to buy us some time.” Instead, when Jester finally got on the phone, “he didn’t want to tell them.” Clearly uncomfortable with playing the heavy, Willumstad told them that Jester could only bring himself to say, “We’re all here, and, you know, we got a big team of people working and we need an extra day or two.”

If Jester spoke to Moody’s the way Willumstad said he did, then there is no doubt in my mind that Jester intended to sabotage the deal. No other explanation is plausible. The importance of the phone call was not unlike that of a death row lawyer seeking a last minute stay of execution. Jester had been the Deputy CFO at Goldman. It would have been his job to deal with the rating agencies regularly. There is no way that he would not have known what to say. All he would need to say is that since AIG’s last meeting with Moody’s, the situation is evolving in a way so Treasury and the Federal Reserve are feeling increasingly confident that the deal being hammered out will significantly ameliorate the company’s liquidity issues. Everyone knows that the rating agencies do not like to abruptly pull the trigger when a situation is still evolving. Everyone also knows that the rating agencies are acutely aware of their chicken/egg role they play in determining a firm’s liquidity situation. (A company has access to the capital markets because of its rating, but its rating reflects its access to the capital markets.) Also, as Janet Tavakoli once mentioned, investment banks train their analysts about how to place pressure on the rating agencies. Finally, it would not have been indelicate to allude to the agencies’ no-so-clean hands in building up the AAA pyramid scheme known as AIGP’s CDO portfolio.

An in case there were any doubt that Jester’s refusal to act as an advocate for AIG made the critical the difference, here’s how Jimmy Lee, of JPMorgan Chase, tallied the numbers on the morning following the downgrades. “They [AIG] have $50 billion in collateral and they need $80 to $90 billion. I don’t know how we can bridge the gap.” Because of the ratings downgrades, AIG posted an additional $32 billion by quarter’s end. In other words, they would have needed about $32 billion less if the downgrades had not taken place.

Minutes after Jimmy Lee briefed his boss, Jamie Dimon. Geithner, Jester Lee and the people from Goldman sat down to figure out what to do next.

September 16, 2008: Paulson installs a CEO at AIG who will favor Goldman.

And a few minutes after Goldman, JPMorgan Chase and the government tried to figure out what was next, at 9:40 a.m., September 16, Goldman CEO Lloyd Blankfein placed a call to Hank Paulson, which Paulson took, even though such communication was illegal. According to Sorkin’s sources, they discussed Lehman and not AIG. Just at the moment when the government was deciding whether to step in and save AIG, Blankfein never mentioned that an AIG collapse could have easily wiped out $15 billion in Goldman’s equity and caused everyone to scrutinize the dodgy CDOs underwritten during Paulson’s tenure. Do you think they just forgot?

As it happened, a few minutes after Paulson got done speaking with Blankfein, Geithner briefed Paulson about a tentative proposal for the government to extend AIG an $85 billion facility. The conversation with Geithner ended at 10:30 a.m.

Sorkin’s sources fabricated a tall tale about what took place afterward:

However resistant Hank Paulson had been to the idea of a bailout, after getting off the phone with Geithner, who had walked him through the latest plan, he could see where the markets were headed and that it scared him. Foreign governments had already been calling Treasury to express their anxiety about AIG’s failing.Jim Wilkinson [Paulson’s deputy, formerly of the White House Communications office] asked incredulously,” are you really going to rescue an insurance company?”

Paulson just stared at him as if to say only a madman would stand by and do nothing.

Ken Wilson, his special advisor, raised an issue they had yet to consider. “Hank, how the hell can we put $85 billion into this entity without new management?”– a euphemism for how the government could fund this amount of money without firing the current CEO and installing its own. Without a new CEO, it would seem as if the government was backing the same inept management that had created this mess.

“You’re right. You’ve got to find me a CEO. Drop every other thing you are doing,” Paulson told him. “Get me a CEO.”

Their choice: Ed Liddy, the former CEO of Allstate and Goldman board member.

The “same inept management that had created this mess”? It’s impossible to overstate the mendacity embedded in that brief passage from Sorkin’s book. If Paulson actually spoke what was on his mind at the time, the words would have been something like this:

“So if we don’t bail out AIG, then Goldman takes a $15 billion hit to its equity and faces shareholder lawsuits for actions taken under my watch. And Willumstad, the new AIG CEO who joined management after all these toxic CDOs were booked, will find it very convenient to also point the finger of blame at Goldman. [Willumstad joined AIG’s board in April 2006, and became CEO in June 2008.] The AIG bankruptcy trustee might even sue Goldman for making fraudulent claims about the CDOs, the same way that HSH Nordbank sued UBS and M&T Bank sued Merrill.

“But if we bail out the company, there’s still no guarantee that Goldman can recover on the CDOs. And Willumstad can still point the finger at Goldman. So before we agree to anything we’ve got to get rid of Willumstad ASAP and replace him with someone who will make sure that Goldman’s interests are being looked after. Let’s use Ed Liddy. He’s a Goldman board member, so he will never disclose anything that makes Goldman look bad. If he wants to preserve the value of his Goldman stock, he’ll discreetly pay off the CDOs before anyone figures out what’s happening. So I decided Willumstad’s replacement will be Liddy, beginning tomorrow, and I don’t give a damn that my unilateral decision to change CEOs overnight is a complete travesty of corporate governance or government accountability. Our story will be that we are replacing the management that created this mess.”

How do I know that this was on Paulson’s mind and that these were his motivations? As noted at the beginning, the guys at Goldman are very smart, and they knew that the CDO settlement was a zero-sum game. Remember, AIG was Goldman’s biggest client and the issue of collateral postings had been in dispute for over a year. Up until June 2008, Ken Wilson was CEO of Goldman’s Financial Institutions Group. There is absolutely no way that Wilson did not know what was going on with AIG’s management, and that Goldman, not Willumstad was primarily culpable for building up the CDO portfolio.

Also, I’ve been a round the block a few times. Whenever faced with a crisis, senior people immediately think about how the situation will reflect on them. And they promptly think about damage control. And like many people who rise to the top, Paulson knows how to avoid leaving fingerprints. He probably learned his lesson decades earlier, working as John Erlichman’s assistant. Like those other famous CEOs, Bernie Madoff and Donald Rumsfeld, Paulson never used e-mail at work. The day after he fired Willumstad, Paulson spoke on the phone with Blankfein five times.

Whoever bore the blame for creating the mess at AIG, it’s extraordinarily reckless, during the middle of a crisis, to immediately install a CEO with no prior experience at the company, which is a huge sprawling conglomerate. That’s especially true when that new CEO has a conflict of interest the size of the Grand Canyon.

Sorkin also makes clear that it was Jester, not Geithner, who took control in structuring AIG’s bailout facility. Before Geithner gets on a conference call with Bernanke:

Jester and [Paulson’s assistant Jeremiah] Norton were poring over all the terms. They had just learned that Ed Liddy had tentatively accepted the job of AIG’s CEO and was planning to fly to New York from Chicago that night. To draft a rescue deal on such short notice, the government needed help, preferably from someone who already understood AIG and its extraordinary circumstances. Jester knew just the man: Marshall Huebner, the co-head of insolvency and restructuring at David Polk & Wardell who was already working on AIG for JP Morgan and who happened to be just downstairs.

Months later, Paulson’s spokesman told The New York Times that, “Federal Reserve officials, not Mr. Paulson, played the lead role in shaping and financing the A.I.G. bailout.”

October 7, 2008: Paulson’s appointee unnecessarily pays out $18.7 billion to the CDO counterparties in exchange for nothing.

Actions speak louder than words, and AIG’s new CEO acted in a way that removed any doubt that he would make decisions in favor of Goldman. Remember, there was no need to hand over anything to the CDO counterparties, because there was no agreed-upon market value for the CDOs, which were all still highly rated. On October 7, 2008, AIG paid out $18.7 in cash in exchange for nothing. Before that October 7, only 26% of the CDOs’ face value had been paid out as cash collateral. Immediately afterward, counterparties hold cash for 56% of the CDOs’ face value of $62.1 billion. All of a sudden, the banks, not AIG, had the upper hand.

November 6, 2008: Only at the point when AIG is once again running out of cash and running out of time, and the CDO banks now hold the upper hand, Geithner is brought in to settle a matter when the government is backed into a corner. (Checkmate anyone?)

On November 5, 2008 only $24 billion remained available under the government’s revolving credit facility, though that cash could have been used up overnight if AIG were downgraded below A-. But, as S&P said, “if mortgage-related losses continue to worsen, then we could lower the ratings into the ‘BBB’ category.”

The CDOs, (which would all be downgraded into the CCC category in a few months), remained a dagger hanging over AIG’s liquidity situation. The only way to restore confidence in the company would be to remove that risk.

But the banks now had the upper hand, since they held most of the cash. Time was not on Geithner’s side, and protracted negotiations over the CDOs’ underlying value could have taken forever. Also, 29% of the remaining CDO exposure belonged to two French banks, whose regulator advised Geithner that it was illegal for them to settle at less than par. Challenging another country’s bank regulator would have opened up a whole can of worms at a point when the risk of global financial panic was very real.

Geithner’s attempts to drive a harder bargain would have created a crisis in confidence that could have likely triggered a further ratings downgrade. The $27 billion to remove the CDO albatross off of AIG’s books was only 15% of the entire $180 billion bailout package.

November 12, 2008: Following public disclosure of the backdoor bailout, Paulson announces his big bait-and-switch: his refusal to use TARP funds to stabilize the mortgage markets.

The collective amnesia of mainstream media notwithstanding, there was full contemporaneous public disclosure of the backdoor bailout of the banks at the time the deal was cut. The bailout package had a lot of moving parts, so it took The Wall Street Journal a day or so before it figured out precisely hat was going on. “New AIG Rescue Is Bank Blessing,” printed on page C1, explained that banks “will be compensated for the securities’ full, or par, value in exchange for allowing AIG to unwind the credit-default swaps.” And for anyone who was slow on the uptake, the Journal printed a picture:

Once the public learned that the CDOs no longer posed a risk to AIG, Paulson announced his his big bait-and-switch: his refusal to use TARP funds to stabilize the mortgage markets. This about face causes the value of all mortgage securities to plummet, imposing an additional loss on Maiden Lane III (and triggering the insolvency of Merrill Lynch).

But Paulson’s coup de grace was to use one of his appointees to fabricate a false history of the backdoor bailout. But that’s for another piece.

Addendum: January 26, 2010 12:50 Bloomberg’s New Puff Piece for Goldman

Once again, Bloomberg has come out with a story that has almost no real facts but plenty of misleading soundbites. From, “Goldman Sachs Drove Most Costly AIG Bargain, Document Shows”:

A month before the September 2008 rescue, Goldman Sachs approached AIG about tearing up contracts protecting the bank against losses on collateralized debt obligations, or holdings backed by mortgages, according to a BlackRock Inc. presentation dated Nov. 5, 2008. Goldman Sachs was the only counterparty willing to cancel the credit-default swaps and bear the risk of further CDO losses, provided that AIG make payments based on the bank’s larger-than-average estimate of market declines.

Tear up the contracts in exchange for what? Par? How much less than par? If you don’t the number, you don’t have a story. Goldman and AIG had been arguing over collateral postings for over a year. A phrase like, “payments based on the bank’s larger-than-average estimate of market declines,” is a meaningless term. Real journalists would put up or shut up.

Instead, we story is padded with lots of empty filler, all of which are used to make Goldman look good. Stuff like:

“We had always made it clear that we were prepared to tear up contracts, it just had to be at the right price,” Lucas van Praag, a spokesman for Goldman Sachs in New York, said in an interview…Goldman Sachs, which created securities tied to home loans and serviced debt on residential properties, “would have had a very decent view of what the underlying mortgage bonds were and what they thought they were worth,” said Thomas J. Adams, a partner at law firm at Paykin Krieg & Adams LLP in New York… <”Goldman was not Pollyanna on what the underlying mortgage bonds were worth,” said Adams, who was a senior managing director in charge of the CDO business at FGIC Corp. from 2006 to 2008. “They were fairly realistic.”

Let’s hope that Bloomberg updates the story with something real.