A different perspective on interest rates

Courtesy of Steve Randy Waldman at Interfluidity

In the endless debates over stimulus and deficits, more “dovish” commentators frequently point out that debt markets appear sanguine about US borrowing. Despite some recent upward jitters, the Federal Government currently pays less than 4% to borrow for 10 years, and under 5% to borrow for 30 years. Those are bargain rates in historical terms, the argument goes, so investors must not be terribly concerned about inflation or default or any other bogeyman of “deficit terrorists”.

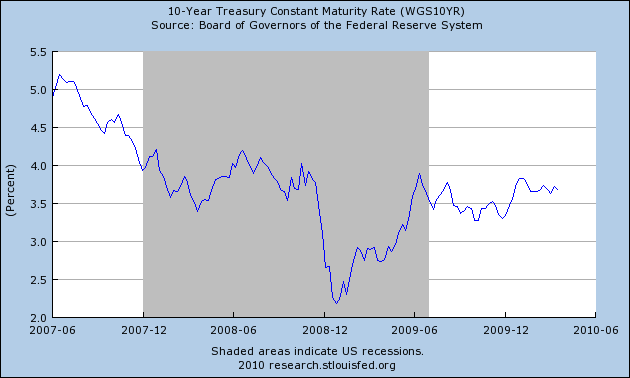

To make the point, Paul Krugman recently published a graph very similar to this one:

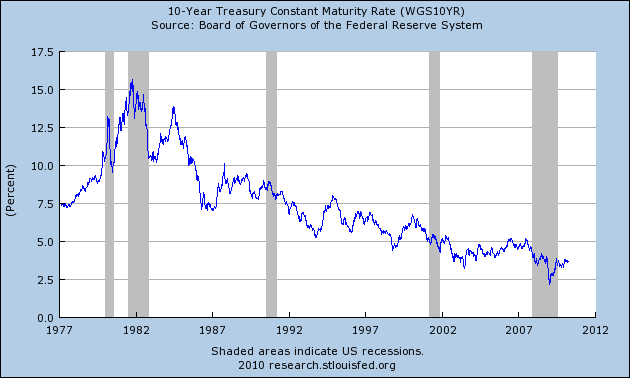

Since the financial crisis began, the US government’s cost of long-term borrowing has dramatically fallen, not risen. If we graph a longer series of 10-year Treasury yields, the case looks even more compelling. The United States government can borrow very, very cheaply relative to its historical experience.

However, there is another way to think about those rates. The US government’s cost of long-term borrowing can be decomposed into a short-term rate plus a term premium which investors demand to cover the interest-rate and inflation risks of holding long-term bonds. The short-term rate is substantially a function of monetary policy: the Federal Reserve sets an overnight rate that very short-term Treasury rates must generally follow. Since the Federal Reserve has reduced its policy rate to historic lows, the short-term anchor of Treasury borrowing costs has mechanically fallen. But this drop is a function of monetary policy only. It tells us nothing about the market’s concern or lack thereof with the risks of holding Treasuries.

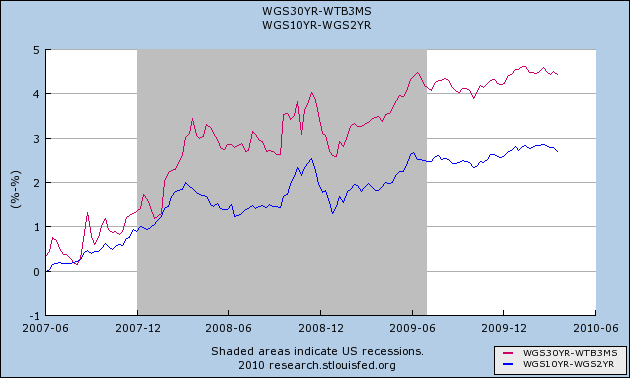

But the term premium (or “steepness of the yield curve”) is a market outcome (except while the Fed is engaged in “quantitative easing”). How do things look when we graph the term premium since the crisis began?

The graph below shows the conventional barometer of the term premium, the 2-year / 10-year spread (blue), and a longer measure, the spread between the yield on 3-month T-bills and 30-year Treasury bonds (red), since the beginning of the financial crisis:

Since the financial crisis began, the market determined part of the Treasury’s cost of borrowing has steadily risen, except for a brief, sharp flight to safety around the fall of 2008. Investors have been demanding greater compensation for bearing interest rate and inflation risk, but that has been masked by the monetary-policy induced drop in short-term rates.

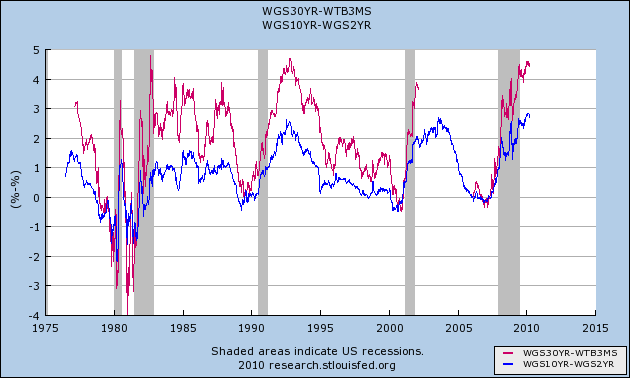

Taking a longer view, we can see that the current term premium is at, but has not exceeded, a historical extreme:

Note: There’s a gap in the 30-year rate series, probably because it became impossible to compute a “constant maturity” 30-year Treasury yield during the period when the Treasury stopped issuing 30-year bonds.

The present term premium is quite similar to those that vexed President Clinton during the heyday of the “bond vigilantes”. A glass half full story says that, despite all the stresses of the financial crisis and the sharp spike in Treasury issuance, the term premium has not become unmoored from its historical range. A glass half empty story says that the term premium is toying with the boundary of that range, and could break loose in an instant. I have no idea which tale is truer.

My politics on the deficit are centrist to dovish. I think that deficit spending is always an option, and that the Federal Government should absolutely spend on forward-looking, high-return investment projects. I also favor generous “safety net” benefits and would like to see a guaranteed income program in the United States. However, the only form of “stimulus” I support is very broad based transfers (e.g. I would support a payroll tax subsidy). I agree with many left-ish commentators that the deficits we’ve experienced are more an effect than a cause of our economic problems, and will take care of themselves if we create a strong economy and a broadly legitimate political system (neither of which I think we have right now). A nation as large and wealthy in natural resources and human capital as the United States need never be constrained by the vicissitudes of financial markets, if its government is capable of mobilizing its citizens’ risk-bearing capacity on behalf of the polity.

But whatever my politics, I think there is a fair probability that the US will experience the thrilling uncertainty that attends a loss of confidence in its currency and debt. The argument that “markets don’t seem troubled by our deficits” is less persuasive than it first appears.

Full disclosure: Although my views are sincerely held, sincerity is cheap. Perhaps I am just talking my book! I am one of those people long gold and short Treasuries (although I am not a proponent of the gold standard).

Remember, economic capital has nothing to do with money. Supplying capital is nothing more or less than assuming the burden of economic risks. Where do you think China’s ever-expanding capital base comes from, when it has been the world’s largest exporter of financial capital? China’s citizens assume great risk, in the form of below-world-market wages and social safety benefits, in exchange for the promise of a wealthier and more powerful nation. To some degree that capital is extracted involuntarily, but China’s government has had remarkable success at maintaining legitimacy and the consent of the governed despite the extraordinary costs citizens have borne in the service of an uncertain future. So far, citizens have seen consistent returns on their investment: the big question is how China fares in a persistent “bear market”, when it comes to seem as though much of their sacrifice has been wasted or stolen.