Foreclosure Fraud For Dummies, Part 2: What’s a Note, Who’s a Servicer, and Why They Matter

Mike Konczal defines the key players in the foreclosure fraud mess. **This is Part 2 in a series giving a basic explanation of the current foreclosure fraud crisis. You can find Part 1 here.

By Mike Konczal, courtesy of New Deal 2.

What is the note?

The SEIU has a campaign: Where’s the Note? Demand to see your mortgage note. It’s worth checking out. But first, what is this note? And why would its existence be important to struggling homeowners, homeowners in foreclosure, and investors in mortgage backed securities?

There’s going to be a campaign to convince you that having the note correctly filed and produced isn’t that important (see, to start, this WSJ editorial from the weekend). It will argue that this is some sort of useless cover sheet for a TPS form that someone forgot to fill out. That is profoundly incorrect.

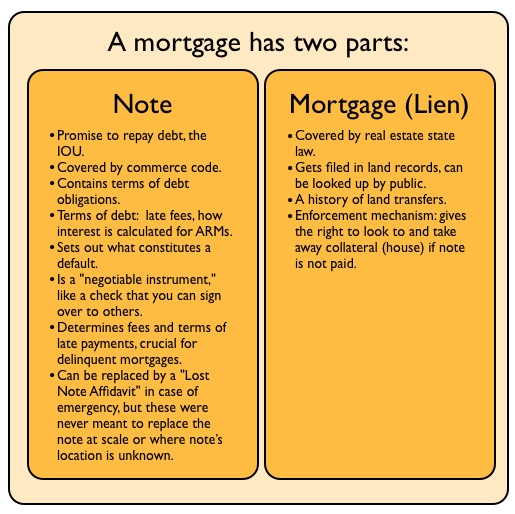

Independent of the fraud that was committed on our courts, the current crisis is important because the note is a crucial document for every party to a mortgage. But first, let’s define what a mortgage is. A mortgage consists of two documents, a note and a lien:

The note is the IOU; it’s the borrower’s promise to pay. The mortgage, or the lien, is just the enforcement right to take the property if the note goes unpaid. The note is crucial.

Why does this matter? Three reasons, reasons that even the Wall Street Journal op-ed page needs to take into account. The first is that the note is the evidence of the debt. If it isn’t properly in the trust, then there isn’t clear evidence of the debt existing.

And it can’t be a matter of “let’s go find it now!” REMIC law, which governs the securitization, is really specific here. The securitization can’t get new assets after 90 days without a tax penalty, and it can’t get defaulted assets at all without a major tax penalty. Most of these notes are way past 90 days and will be in a defaulted state.

This is because these parts of the mortgage-backed security were supposed to be passive entities. They are supposed to take in money through mortgage payments on one end and pay it out to bondholders on the other end — hence their exemption from lots of taxes. The tradeoff is that they can’t be de facto managers of assets, and that’s what going to find the notes would require.

For Distressed Homeowners

The second is that it also matters a great deal for homeowners who are distressed. The note lays out the terms of late fees and other penalties. As we will discuss in the section on mortgage servicers, the process of trying to get people who are behind on their payments current instead of driving them into bankruptcy has broken down. But for now, it’s clear that mortgage servicers don’t have great incentives to get distressed homeowners’ records correct.

There’s well-documented evidence that extra fees are tacked on to mortgages that have fallen behind, fees that aren’t following the terms of the note. This is usually only found out in bankruptcy where there is a lawyer (and multiple parties), not in foreclosure cases. But the terms of the note are necessary for the court if homeowners wants to challenge the servicers’ claim of the final due amount.

This will matter a great deal for many homeowners. Small, marginal differences in the total owed could allow for a short sale. It could determine if the homeowner has any equity in their home. And this can only be determined by producing the note.

For Investors, Who Took This Seriously at the Beginning

Last reason: you can tell it’s important because all the smartest finance guys in the room thought it was important. Let’s look at a Pooling and Service Agreement form from 2006 (PSA) between “GS MORTGAGE SECURITIES CORP., Depositor, and DEUTSCHE BANK NATIONAL TRUST COMPANY, Trustee.” (h/t Adam Levitin for this example.) Let’s reproduce the chart from part 1 to see the chain between depositors and trustees who oversee the trust:

So what agreement did they come to when it comes to the proper handling of notes in securitization? Did they think this was no big deal, or that it is something serious? From the PSA (my bold):

(b) In connection with the transfer and assignment of each Mortgage Loan, the Depositor has delivered or caused to be delivered to the Trustee for the benefit of the Certificateholders the following documents or instruments with respect to each Mortgage Loan so assigned:

(i) the original Mortgage Note (except for up to 0.01% of the Mortgage Notes for which there is a lost note affidavit and the copy of the Mortgage Note) bearing all intervening endorsements showing a complete chain of endorsement from the originator to the last endorsee, endorsed “Pay to the order of _____________, without recourse” and signed in the name of the last endorsee…

The Depositor shall use reasonable efforts to cause the Sponsor and the Responsible Party to deliver to the Trustee the applicable recorded document promptly upon receipt from the respective recording office but in no event later than 180 days from the Closing Date….

In the event, with respect to any Mortgage Loan, that such original or copy of any document submitted for recordation to the appropriate public recording office is not so delivered to the Trustee within 180 days of the applicable Original Purchase Date as specified in the Purchase Agreement, the Trustee shall notify the Depositor and the Depositor shall take or cause to be taken such remedial actions under the Purchase Agreement as may be permitted to be taken thereunder, including without limitation, if applicable, the repurchase by the Responsible Party of such Mortgage Loan.

Read that again through to the end and use the chart to follow the chain. If more than 0.01% (!) of mortgage notes weren’t properly transferred, the trust can force the sponsor (in this case, Goldman Sachs) to repurchase the bad mortgages. And this is just one contract for one part of the ~$2.6 trillion dollar mortgage backed securities market. How’s that for systemic risk? Especially if this is found to be widespread…

Looking at the documents, you see that the smart guys who created these mortgage-backed securities put large poison pills into them to try and prevent the kind of note fraud we are currently experiencing. They took the policing and legal recourse (and legal ability to cover themselves) very seriously on this issue. So seriously they can force repurchases of this bad debt.

So don’t believe anyone who says these are just technicalities; the people who wrote the contract didn’t believe they were.

Who is a servicer?

Whenever I hear someone say there wouldn’t be a problem with foreclosures if people just paid their mortgages on time, I’m reminded of Alan Grayson’s paraphrase of the Republican Health Care Plan: “Don’t Get Sick. If You Get Sick, Die Quickly.” Yes, the world would be an easier place if people never got sick, or credit risk didn’t exist, and people made payments perfectly all the time. But they don’t, and we need a system of rules and a process for collecting and presenting evidence in order to kick a family out of their home. And we need a system where this process sets the ground rules that in turn allow for lenders and borrowers coming together and negotiating a situation that is best for both of them.

Because the first rule of mortgage lending is that you don’t foreclose. And the second rule of mortgage lending is that you don’t foreclose. I’ll let Lewis Ranieri, who created the mortgage-backed security in the 1980s, tell you: “The cardinal principle in the mortgage crisis is a very old one. You are almost always better off restructuring a loan in a crisis with a borrower than going to a foreclosure. In the past that was never at issue because the loan was always in the hands of someone acting as a fudiciary. The bank, or someone like a bank owned them, and they always exercised their best judgement and their interest. The problem now with the size of securitization and so many loans are not in the hands of a portfolio lender but in a security where structurally nobody is acting as the fiduciary.”

In the past you had Jimmy Stewart banks. The mortgages were kept on the bank’s books. You had someone who you could go to in order to renegotiate your mortgage. With mortgage-backed securities, the handling of payments and working-out of troubles moved to servicers. If you are learning about this crisis for the first time, understanding what is broken here is very important.

This is Not a New Problem With Servicing

Let’s get some quotes from bankruptcy judges in here:

“Fairbanks, in a shocking display of corporate irresponsibility, repeatedly fabricated the amount of the Debtor’s obligation to it out of thin air.” 53 Maxwell v. Fairbanks Capital Corp. (In re Maxwell), 281 B.R. 101, 114 (Bankr. D. Mass. 2002).

“[T]he poor quality of papers filed by Fleet to support its claim is a sad commentary on the record keeping of a large financial institution. Unfortunately, it is typical of record-keeping products generated by lenders and loan servicers in court proceedings.” In re Wines, 239 B.R. 703, 709 (Bankr. D.N.J. 1999).

“Is it too much to ask a consumer mortgage lender to provide the debtor with a clear and unambiguous statement of the debtor’s default prior to foreclosing on the debtor’s house?” In re Thompson, 350 B.R. 842, 844–45 (Bankr. E.D. Wis. 2006).

(Source.) Notice that consumer rights groups were flagging this as a major problem back in 1999 and 2002 because judges were noticing it was a major problem in their bankruptcy courts. If the late 1990s to 2006 period is a Renaissance period of servicer fraud, then we can contrast it with the period we live in now, the Baroque period of servicer fraud. Whatever unity there used to be between the forms and functions of the sloppy documentation and outright fraud in the art of servicing have become detached.

The forms of fraud have gone high art: serving documents on people who could never have been served, signing 10,000 affidavits a month, etc. They are all well-covered, and we’ll list more later perhaps. Here are some of my favorites from last year, the reading list in Part One has even more. But what I want to focus on is the function of servicer fraud.

What Do Servicers Do? A Case Study in Bad Design and Worse Incentives

Servicers in a mortgage-backed security have two businesses. The first is transaction processing. This means taking in your mortgage money on one end and walking it over to the crazy tranches and payment waterfalls on the other end. This is clean, efficient, largely automated, requires little discretion and works very well, and implicit in it is that it is most profitable when you can harness economies of scale.

In fact, it’s considered a “passive entity”, so there are no taxes applied in this passthrough mechanism. If servicers went “active”, say by looking for mortgage notes not in the trust 90 days after the fact or mortgage notes that are not in the trust that have defaulted (which is what they’d likely have to do to get out of this foreclosure fraud crisis), they’d face very severe tax penalties.

Their other business is to handle default situations. In addition to the fixed fee they get for servicing each individual mortgage, they get paid by default fees like late charges. They get to retain most, if not all, of these fees.

So right away they have a disincentive to negotiate to get a mortgage in a good state. They also have a strong incentive to keep a steady stream of fees and charges going to their books, rather than to investors. So anything that puts servicers in charge of negotiating mortgages, say the Obama’s administration’s HAMP program, is designed to fail.

Because even without bad incentives, doing good work on modification is costly, time consuming, requires individual expertise and experience and doesn’t benefit from automation or economies of scale. Which is to say it has the opposite structure of their normal business.

And there are additional worries. Many of the servicers work for the largest four banks — Wells Fargo, Bank of America, Citi, and JP Morgan — and these four banks have large exposures to junior liens. These are second or third mortgages or home equity lines of credit that would have to be wiped out before the first mortgage can be modified. The four banks have almost half a trillion dollars worth of these exposures and, from the stress test, are valuing them at something like 85 cents on the dollar. Keeping a homeowner struggling to pay the second lien would be more worthwhile to these middlemen banks than getting him or her into a solid first lien to the benefit of the bond investor.

So keep these in mind as you read about the servicers here. There have been worries that they, as a designed institution, were simply not qualified for this job going back a decade. They have massive conflicts with the investors they are supposed to be working for. They profit when homeowners collapse and lose money when they are brought up to a normal payment schedule (made current). And if the instruments don’t have the notes necessary to bring standing to carry out the foreclosures, they have to take a massive tax hit in order to take the note into the trust. And there is no regulation in place to handle this.

No Regulator

Because for all the talks of regulatory burden, there is no current federal government agency that regulates the servicers. Not the Federal Reserve. Not the Treasury. This is what happens when the financial industry writes the deregulation. Instead, you have a patchwork of state regulators and attorney generals. Notice how President Obama has nobody to turn to and tell the press that “So and So is on the case.” In theory, the OCC regulates servicers if they are part of a bank or a thrift. This regulation must fall to the new regulatory counsel and the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau to investigate, where it will properly belong.

(The Fair Debt Collections Act, which applies to debt collectors, doesn’t apply to servicers. Here’s a fun idea for an enterprising staffer: if there is no producible note, are servicers still legally servicers and thus exempt from the Fair Debt Collections Act? Just a thought…)

Is it any wonder that servicers are rushing these foreclosures and making a mockery of the courts and producing systemic risk in the process? There needs to be an investigation of what is being done and why, because this problem is not taking care of itself.

(Special thanks to Katie Porter and Adam Levitin, who you can read at credit slips, as well as Tom Adams and Yves Smith, who you can read at naked capitalism, for in-depth discussions on this material.)

Mike Konczal is a Fellow at the Roosevelt Institute.

[Sign up for weekly ND20 highlights, mind-blowing stats, event alerts, and reading/film/music recs.]