Courtesy of www.econmatters.com.

By EconMatters

The latest move on China politics at Washington is the China currency bill, due at the U.S. Senate on Tuesday, Oct. 11. The proposal would levy tariffs on China and four other Asian countries for artificially depressing the value of their currencies to boost their exports.

To us, it seems evident that those in Washington have not thought this through completely (or chose to ignore). Here is how the math would work.

According to the government trade data, China imports from the U.S. about $57.7 billion for the first 7 months of 2011 ($100 billion annualized), and the number will only grow with increasing Chinese household income. So just based on pure math, the Big Question #1 is this:

How many American jobs will be lost if the U.S. loses all or even part of the $100 billion annual export business with China when China retaliates with similar tariffs on U.S. goods?

The same math works for the U.S. imports from China, which is at about $374 billion annualized using the July 2011 year-to-date figure. So the Big Question #2 is:

How much damage would the U.S. tariff on Chinese imported goods do to the pocketbook of American business and consumers?

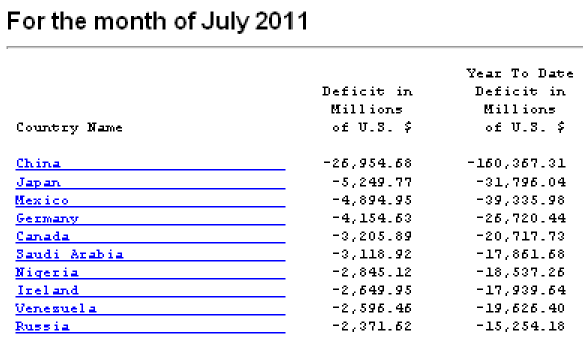

It seems many are quite fixated on the trade deficit number the U.S. has with China. However, as the table (showing the top 10 countries) and chart below illustrates, America runs trade deficits with many other trading partners, not just China. And realistically, the total trade deficit of $160.4 billion for the first seven months of 2011, even if completely reversed to zero, is a tiny drop in the big bucket of the $14-trillion U.S. economy.

The point is that even if China revalues Yuan to Washington’s satisfaction, it will not have the significant impact to the U.S. economy and jobs as some are led to believe.

|

| Chart Source: U.S. Census Bureau |

One strong support of this currency bill is that by keeping the Chinese Yuan artificially low, many American jobs have lost/outsourced to China; whereas in fact, tax is actually one of the biggest considerations that U.S. corporations have moved operations overseas, including China.

Another reason China has become attractive to many western firms (including the U.S.) is the access to a large and highly educated work force on a lower pay scale. Due to the long ingrained cultural belief that values higher education, China has too many college graduates that the domestic economy can’t fully absorb yet.

Apple, for example, has a huge China operation with Foxcom producing its popular i products, but hit a wall at Brazil. Reuters reported that Apple’s $12 billion iPad deal with Brazil came to a screeching halt partly due to “Brazil’s own deep structural problems such as a lack of skilled labor,” high taxes and bad infrastructure.

In addition to decades of anti-business policies, including unfavorable tax treatments and bureaucratic regulations, to disincentivize establishing business at home, the U.S. also has similar structural problems to those of Brazil in labor and infrastructure.

A few forecasts we have seen so far already indicate that the U.S. is not producing enough college educated work force to even fuel its normal growth. On the infrastructure side, according to the estimate by the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE), America is in need of $2.2 trillion investment to high-grade the aging and outdated infrastructure up to where they should be.

Now, since the central focus of this latest currency bill is China’s “currency manipulation”, we can take a look at other countries that have also dabbled in this sport.

For instance, Japan has repeatedly intervened in the currency market over the years. So, does the massive unprecedented G7 Yen intervention in March count? How about when Swiss National Bank (SNB) vowed to “defend” the minimum EUR/CHF exchange rate at 1.20 with some very sizable interventions in the open currency market?

The two aforementioned examples may all have perfectly legitimate reasons, but they highlighted the fact that no country wants a strong currency which hurts its export business. Many central banks have intervened in the currency market (some well publicized, some more “discrete”) when its currency put the country at a disadvantage. And these past interventions will not be the last either.

On that note, China most likely could make a fairly good argument that the U.S. Fed’s programs of QE’s, Twist, the rising federal deficits, and debt are all just part of the effort by the U.S. government to debase the Dollar in order to have the trade advantage over rival currencies as well.

Also from a logical point of view, should the bill not be amended to include all of the U.S. trading partners who have engaged in currency intervention activity? If so, then the Big Question #3 would be:

Is the U.S. ready for a global trade war?

So it is quite hypocritical for the politicians at Washington to single China out when there are many other countries (including the U.S.) doing exactly the same thing.

What it comes down to is that many U.S. politicians are facing reelection in 13 months, and China currency bill is one easy mark to show voters that they are doing something to address the unemployment issue. However, one such bill would come with a hidden high price tag and serious repercussion to the U.S. economy that taxpayers can not afford to foot.

Even if Washington has the answers and contingency plans in place for the 3 Big Questions asked herein (which is highly improbable, and also begs the question of risk/reward and value-add), the currency bill is nothing more than politics to save their own jobs in the next election, instead of one with any kind of economic considerations.

Frankly, in light of the U.S. debt and deficit shamble, lawmakers would be much better off focusing on cleaning the fiscal house (and not to repeat the embarrassing debt ceiling debate to get yet another sovereign credit downgrade), instead of spending precious time and energy taking on China and/or any of the trading partners over currency valuation.