Courtesy of Trader Mark of Fund My Mutual Fund

Normally we focus on public companies for obvious reasons, but this Fortune story on privately held Cargill is quite interesting in many aspects, so I thought I’d pass it along. The only association market wise I’ve had with Cargill is it’s holdings of fertilizer Mosaic (MOS), but it certainly is a company that has its hands in all of our lives, via the food chain. I did not realize how massive it was – it is double the size (by revenue) of Archer Daniels Midland (ADM). It’s the largest private company in the United States, and if public would be #18 on the Fortune 500 ahead of IBM.

Worth heading over to Fortune to read the whole piece (fascinating section about how Cargill brought cocoa harvesting to Vietnam since it had similar climate to the Ivory Coast) but I’ll bring over some excerpts:

- With $119.5 billion in revenues in its most recent fiscal year, ended May 31, Cargill is bigger by half than its nearest publicly held rival in the food production industry, Archer Daniels Midland (ADM). If Cargill were public, it would have ranked No. 18 on this year’s Fortune 500, between AIG (AIG, Fortune 500) and IBM (IBM, Fortune 500). Over the past decade, a period when the S&P 500’s revenues have grown 31%, Cargill’s sales have more than doubled.

- But those numbers alone don’t begin to capture the scope of Cargill’s impact on our daily lives. You don’t have to love Egg McMuffins (McDonald’s buys many of its eggs in liquid form from Cargill) or hamburgers (Cargill’s facilities can slaughter more cattle than anyone else’s in the U.S.) or sub sandwiches (No. 8 in pork, No. 3 in turkey) to ingest Cargill products on a regular basis. Whatever you ate or drank today — a candy bar, pretzels, soup from a can, ice cream, yogurt, chewing gum, beer — chances are it included a little something from Cargill’s menu of food additives. Its $50 billion "ingredients"

business touches pretty much anything salted, sweetened, preserved, fortified, emulsified, or texturized, or anything whose raw taste or smell had to be masked in order to make it palatable. - Despite Cargill’s extraordinary size, strength, and breadth, it has long been remarkably successful at keeping out of the public eye. But the days when the company could get away with saying nothing and revealing less are over. "I think the world has curiosity about where its food comes from that is more earnest than it’s been in the past," says Page, who earlier this year took the unprecedented step of allowing Oprah’s cameras inside a Cargill slaughterhouse. (No video of the actual slaughtering, however.)

- The simple fact is that the bigger Cargill gets, the more attention it draws. Timothy Wise, research director at the Global Development and Environment Institute at Tufts University, points to several factors that have increased concerns about Cargill’s rising power, including recent wild gyrations in commodities markets, "sticky-high" prices at the supermarket, and the ever deeper integration of Big Ag with global financial markets.

- Perhaps the most hot-button issue of all is food safety. In August, Cargill announced the largest poultry recall in U.S. history — 36 million pounds of ground turkey linked to a salmonella outbreak at a factory in Arkansas that sickened 107 people in 31 states and killed one. "The public is justified in being wary of having any part of our food system controlled by a small number of large corporations," says Wise.

- Page is the third CEO in a row to come from outside the family. Today not a single Cargill or MacMillan remains in a senior executive position at the company. Outsiders (six) and managers (five) outnumber family members (five) on the board. What hasn’t changed is ownership. Cargill introduced a limited employee stock ownership plan in the ’90s that allowed some family members to cash out. However, roughly 100 descendants of the founders still own around 90% of the stock, worth some $52 billion as of the last official tally.

- Cargill ships other commodities too: soybeans and sugar from Brazil; palm oil from Indonesia; cotton from Asia, Africa, Australia, and the Deep South; beef from Argentina, Australia, and the Great Plains; and salt from all over North America, Australia, and Venezuela. The company owns and operates nearly 1,000 river barges and charters 350 oceangoing vessels that call on some 6,000 ports globally, ranking it among the world’s biggest bulk shippers of commodities. "In one sense, you can think of Cargill as just a big transportation company," says Wally Falcon, deputy director at the Center on Food Security and the Environment at Stanford University. "Their game is: extremely efficient, high volumes, low margins, and just being smarter and quicker than anybody else."

- Sometimes the same ship that picks up a load of soybeans at Cargill’s deepwater Amazon port in Santarem, Brazil, after unloading in Shanghai, will carry coal from Australia to Japan before rinsing out its holds and returning to Brazil for more beans. In fact, Cargill’s ocean-transport business moves more coal and iron ore for third parties than it does foodstuffs, oils, and animal feeds for itself, by a factor of two.

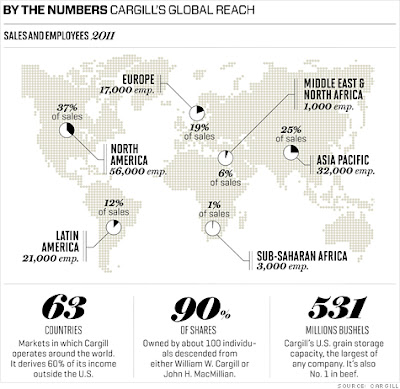

- Cargill reluctantly sold its 64% stake in fertilizer manufacturer Mosaic (MOS) for $19 billion earlier this year, and it exited the seed-engineering business long ago. But farmers in many of the 63 countries where Cargill operates — 60% of earnings are generated outside the U.S. — can still buy everything they need to plant their crops and feed their livestock from a local Cargill rep, as well as crop insurance, hedging instruments, and marketing advice.

- As mighty as Cargill may be, it is not immune to setbacks. In fact, the company’s fiscal 2012 is off to a dismal start. Revenues rose 34% in the quarter ended Aug. 31, but earnings were down 66%. That after earnings rose more than 60% in the first quarter of fiscal 2011.

- Page blames a perfect storm of unforeseen events: spring flooding in the Midwest (Cargill spent $20 million to prevent the Missouri River from washing out its corn-milling plant in Blair, Neb.); the salmonella outbreak in its turkey plant, which led to a partial shutdown and layoffs ("instead of a business that was making money, we have one absorbing the costs of the recall"); a significant wrong bet on a single, unnamed commodity; a "risk-on, risk-off" market environment that otherwise neutralized Cargill’s vaunted trading expertise; and, above all, the global recovery that wasn’t. "We underestimated the degree to which the world was gonna back up," says Page.

- Remarkably, though, Cargill didn’t slow down. The company maintained what Page calls a "big acquisition agenda," completing deals for a Central American poultry and meat processor, a German chocolate company, an Italian feed company, and the grain business of AWB Ltd., formerly the government-owned Australian Wheat Board. (Page says the $1.3 billion AWB purchase fills a hole in Cargill’s global grain network: "We’re in Russia," says Page, "we’re in the Ukraine, we’re in Canada, we’re in the U.S., we’re in Argentina, and we just didn’t have as vibrant a footprint there.") Cargill also has a pending $2.1 billion offer for Provimi, a global feed company with 7,000 employees in 26 countries; that deal is expected to close by year-end.

- Few public companies could be that aggressive after bad results. "People always ask, ‘Why is Cargill private?’ " says Page. "This is probably one of those moments."

- Page may not be under pressure from the family shareholders, but that doesn’t mean that he is unworried about the future. The real threat to Cargill’s long-term prosperity, Page says, is that forces beyond the company’s control will infringe on its freedom to operate across markets. Cargill is clearly concerned with the way the global conversation is bending on food security. "You don’t want to end up with policies that are counterproductive to feeding everyone," says Page, "and we don’t want to end up with a business model that doesn’t have any freedom to operate."