Courtesy of The Automatic Earth

"W.T. Grant department store fire at New York’s Sixth Avenue and 18th Street in April 1916"

Ilargi: Oh, sure, don’t get me wrong, there may still be a Euro a year from now. And there’ll certainly be some investors left.

But the Euro, if it manages to survive, will have to do so in what can only be characterized as a radically different form and shape. At the same time, small mom and pop stock investors will be few and far between; there’s no money in the "traditional" stock markets, as they’ve found out – once more – in 2011. Many will also need what money they still have in stocks to pay down various kinds of other obligations.

As for the stock markets, I found it greatly ironic that on December 23, the S&P 500 was up for the year. Yesterdays markets plunge did away with that irony, but given the psychological importance, I wouldn’t be surprised if, in the slim trading volume between Christmas and New Year’s, one party or another will make sure the number comes in positive anyway.

What strikes me in all this is the disparity between the S&P and financial stocks. It’s unreal. If mom and pop hold bank stocks, they’re not very likely to have turned a profit. If pension funds are anything to go by (they lost big time this year), mom and pop had lean turkey at their holiday family parties.

Here’s a little overview of the year-to-date performance of some of the major global banking stocks on December 29, 2011, before the opening bell:

- BofA: -60.38%

- Citi: -44.76%

- Goldman Sachs: -46.41%

- JPMorgan: -23.03%

- Morgan Stanley: -45.24%

- RBS: -50%

- Barclays: -34.32%

- Lloyds: -63.02%

- UBS: -29.33%

- Deutsche Bank: -28,55%

- Crédit Agricole: -56.04%

- BNP Paribas: -37.67%

- Société Générale: -59.57%

These are just some of the Too Big To Fail institutions. And while your governments have enough faith in them – or so they want you to believe – to prop them up with trillions of dollars of your money, investors are fleeing them, even if they can expect them to be propped up further.

That doesn’t just say something about confidence in the individual banks, it shouts loud and clear from the rooftops on confidence in the banking system as a whole, and indeed on governments’ ability to continue bailing them out. In other words: bailouts don’t build confidence, they are taken as a sign that trouble’s on the way.

Mom and pop will finally clue in to this in 2012, and get -their money- out of harm’s way. Well, either that or lose it. Their money, that is. Perhaps their minds too. And their homes. Their jobs.

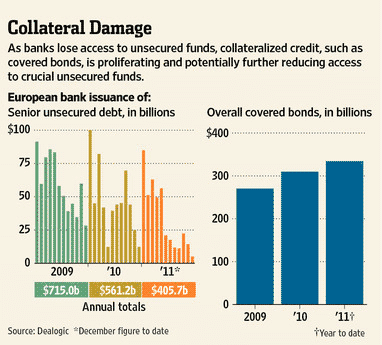

Of the banks above, the European ones are in even deeper doodoo than their US counterparts. Gordon T. Long, in a report called Collateral Contagion, lifts a hitherto little known part of the veil:

There are approximately $55 trillion of banking assets in the EU. This compares to only $13 trillion in the US. Bank assets in the EU are 4 times as large as in the US.

In the US, debt held by the bank is smaller because retail deposits are a primary source of funds. EU banks use wholesale lending and, as a consequence, the debt held by banks is close to 80% versus less than 20% by US banks.

Wholesale bank lending in the EU approximates $30 trillion versus only $3 trillion in the US, a 10 X differential.

Wholesale lending is fundamentally borrowing from money market funds and other very short term, unsecured instruments. The banks borrow short and lend long. It all works until short term money gets scarce or expensive.

Both have occurred in the EU and this recently placed Dexia into bankruptcy, forcing it to be taken over by the Belgian and French governments. The unsecured bond market fundamentally closed in the EU in Q3 2011, as fears mounted that an EU solution was not forthcoming.

Assuming $30 trillion of loans is spread over three years, EU banks have a requirement for $800 billion a month of rollover financing for wholesale lending outstanding.

Ilargi: If those numbers don’t render you speechless, please read them again. $800 billion a month of rollover financing, every single month for three years.

The ECB recently passed out €489 in three-year loans at 1%. Nobody was impressed for more than a few hours. Gordon T. Long’s report reveals at least a part of the reason why. Moreover, the ECB is now accepting the proverbial toilet paper as collateral for the loans, but guess what, banks are running out of toilet paper! David Enrich and Sara Schaefer Muñoz touch on the same topic for the Wall Street Journal:

Europe’s Banks Face Pressure on Collateral

Even after the European Central Bank doled out nearly half a trillion euros of loans to cash-strapped banks last week, fears about potential financial problems are still stalking the sector. One big reason: concerns about collateral.

The only way European banks can now convince anyone—institutional investors, fellow banks or the ECB—to lend them money is if they pledge high-quality assets as collateral.

Now some regulators and bankers are becoming nervous that some lenders’ supplies of such assets, which include European government bonds and investment-grade non-government debt, are running low.

If banks exhaust their stockpiles of assets that are eligible to serve as collateral, they could encounter liquidity problems. That is what happened this past fall to Franco-Belgian lender Dexia SA, which ran out of money and required a government bailout."Over time it is certainly a risk," said Graham Neilson, chief investment strategist for Cairn Capital Ltd. in London. "If banks don’t have assets good enough to pledge as collateral, they will not be able to tap as much liquidity…and this could be the end-game path for a weaker bank."

Ilargi: The market for unsecured bonds issued by banks is dead. And they no longer have any collateral left to issue secured bonds. So what will they do?

Saw this Guardian headline yesterday: Liquidity crunch fears stalk markets. I’d say that should have read Solvency crunch fears stalk markets. The ECB has taken care of short term liquidity. But to no avail.

Collateral equals solvency. The ECB loans equal liquidity. And liquidity means nothing if you’re insolvent. Inevitably, banks will start to fall by the wayside. Even some of the Too-Big-To-Fail ones.

As will countries. There is no chance – well, I’ll give you 1% or 2% – that Greece will still be part of an unchanged Eurozone a year from now. Chances for Portugal, Ireland, Italy and Spain may be a bit higher, but certainly not by much. France will face huge market pressure. And presidential elections.

The road going forward has become completely unpredictable. For you and me, and also for our "leaders". They don’t like that, even less than we do. That’s why we saw this report from Philip Aldrick in the Telegraph a few days ago:

UK treasury plans for euro failure

The Government is considering plans to restrict the flow of money in and out of Britain to protect the economy in the event of a full-blown euro break-up.[..]

Officials fear that if one member state left the euro, investors in both that country and other vulnerable eurozone nations would transfer their funds to safe havens abroad. [..]

Under European Union rules, capital controls can only be used in an emergency to impose "quantitative restrictions" on inflows, [..]

Capital controls form just one part of a broader response to a euro break-up, however. Borders are expected to be closed and the Foreign Office is preparing to evacuate thousands of British expatriates and holidaymakers from stricken countries.

The Ministry of Defence has been consulted about organising a mass evacuation if Britons are trapped in countries which close their borders, prevent bank withdrawals and ground flights.

Every government, in Europe and in the US, is busy working on contagion plans, just like this one, over the holidays. Bank holidays are considered, capital controls, travel restrictions.

In order to keep the basics of their economies going in case of financial disaster, governments will need to make sure they have the means to cover basic necessities. In a world where most of the energy and food is imported, that is a herculean task.

Who’s going to issue the letters of credit that make imports possible? And what will they be covered with? Will Saudi Arabia, Russia, China and the US still accept euros when the defection of Greece and/or others makes the future of the Eurozone and the entire EU highly uncertain? No, they will probably want guarantees in US dollars.

As we speak, the euro is getting hammered, as is sterling, as is gold. Or are they? Or is it perhaps that the USD is rocking, in anticipation of near-future demand?

The risks for Europe come from all sides now, and at some point, which I think could be very close, one of these risks will not be -fully- covered. Because of the close interconnectedness between EU countries, as well as that between European and global financial institutions, one single domino may set in play a chain of events that will be beyond governments’ control.

And, as I said, they don’t like that. They may opt to pre-empt any such possible events. In the Eurozone alone, we’re looking at 17 different governments who may decide to do so, in whatever way. Leave the Eurozone, leave the EU, stall decision making, refuse to pay debt. 17 different governments, many of whom will change during the course of the year, have multiple options that would derail the entire EU project as it was intended to be.

While sovereign and private debt is certain to keep on rising, and willingness to lend in order to stave off defaults is disappearing.

No, I don’t know what the euro will look like next Christmas, but it won’t be what it looks like today. It could be the return of the drachma and lira, or the return of the mark and guilder, or all of the above. But not a 17 countries’ Eurozone.

Nontas Stylianidis, AFP, Getty Images Burning Greek 2011

A bit more Europe. I’m spending some time in Holland, and wrote down the following over Christmas:

Holland has already officially confirmed it is in recession. And this at a point in time when its gigantic housing bubble hasn’t even started popping yet. With mortgage debt at anywhere between €650 billion (official government number) and €1 trillion (Ernst & Young, unconfirmed by me) for its 16.7 million citizens, and taking into account that only an estimated 50% of Dutch are homeowners to begin with, it should be obvious that a "mere" 10% or 20% drop in prices would be devastating.

If 9 million (well over that 50%) Dutch men, women and children bear that €650 billion debt, each and everyone of them carries over €72,000. A typical family of 4 is then €288,000 ($375,000) in debt. On average! The huge popularity of interest-only mortgages has undoubtedly contributed strongly to this debt proliferation. And most will still feel fine, because the inevitable fall in prices hasn’t materialized yet. And, admittedly, there are substantial savings.

Any drop in prices beyond 20% would mean unmitigated disaster. A huge part of private savings would be wiped out, and the banks that hold the mortgages would be pushed further into their already bankrupt status. Given the near inevitability of one or more countries leaving the Eurozone, even after trillions of euros were spent to prevent just this from happening, it’s hard to see what the government could do to stave off widespread financial mayhem.

That same government did launch one idea last week: it seeks to force the country’s "home-building corporations", a left-over from post-WWII state building projects aimed at offering affordable rental homes to everyone, to sell 75% of their rental homes to present occupants (at "reasonable" prices…). That’s a lot more potential debt slaves in one fell swoop. Whether or not a government, any government, should aim for just that is quite another matter.

This is one of Europe’s richest countries. Or so everyone seems to think. Europe is rotten at the core too, not just the periphery.