Courtesy of The Automatic Earth

Guanica, Puerto Rico. "Burning a sugar cane field. This process destroys the leaves and makes the cane easier to harvest"

Ilargi: No, I’m not talking about the fact that Germany and Holland want to take over as the de facto government in Greece, as Noah Barkin writes for Reuters (that they want to do it through Brussels is a mere technicality).

Germany wants Greece to give up budget control

Germany is pushing for Greece to relinquish control over its budget policy to European institutions as part of discussions over a second rescue package, a European source told Reuters on Friday.

"There are internal discussions within the Euro group and proposals, one of which comes from Germany, on how to constructively treat country aid programs that are continuously off track, whether this can simply be ignored or whether we say that's enough," the source said.

The source added that under the proposals European institutions already operating in Greece should be given "certain decision-making powers" over fiscal policy. "This could be carried out even more stringently through external expertise," the source said.

The Financial Times said it had obtained a copy of the proposal showing Germany wants a new euro zone "budget commissioner" to have the power to veto budget decisions taken by the Greek government if they are not in line with targets set by international lenders.

"Given the disappointing compliance so far, Greece has to accept shifting budgetary sovereignty to the European level for a certain period of time," the document said. Under the German plan, Athens would only be allowed to carry out normal state spending after servicing its debt, the FT said.

Ilargi: Nor do I mean the report from the Kiel Institute for the World Economy that Ambrose Evans-Pritchard cites for the Telegraph, and which implies a second bailout for Portugal is looming near:

Investors fear mounting losses in Portugal as second rescue looms

Portugal is fighting a losing battle to contain its public debt and may be forced to impose haircuts of up to 50pc on private creditors, according to a top German institute.

A report for the Kiel Institute for the World Economy said Portugal would have to run a primary budget surplus of over 11pc of GDP a year to prevent debt dynamics spiralling out of control, even in a benign scenario of 2pc annual growth.

"Portugal's debt is unsustainable. That is the only possible conclusion," said David Bencek, the co-author, warning that no country can achieve a primary budget surplus above 5pc for long. "We won't know what the trigger will be but once there is a decision on Greece people are going to start looking closely and realise that Portugal is the same position as Greece was a year ago."

Yields on Portugal's five-year bonds surged on Thursday to a record 18.9pc, reflecting fears that the country will need a second rescue from the EU-ECB-IMF Troika. Three-year yields hit 21pc.

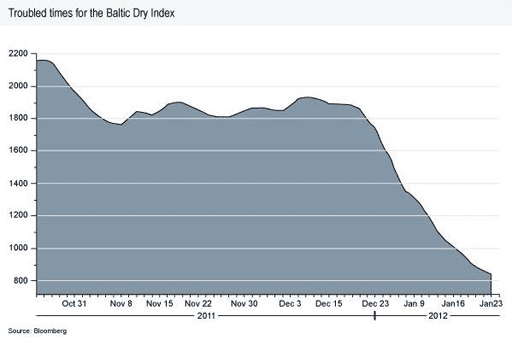

Ilargi: Or even the true meaning behind the steep drop in the Baltic Dry Index, on which Sebastian Walsh reports for Financial News:

Chart of the Day: The Baltic Dry Index

Statistics from the Office of National Statistics this morning showed that the UK went into reverse in the last quarter of 2011, when the economy shrank by 0.2% – but as the Baltic Dry Index shows, the global economy is looking even more worrying.

The index – often used as a proxy for the health of the global economy as it reflects the prices charged for shipping commodities such as metals, coal or grain around the world – has fallen by 61% since October. The index was at 842 at yesterday’s close – down from its 12-month high of 2173 last October.

Nick Bullman, managing partner at risk consultant Check Risks, said the index is a good way of looking at the risks to the global economy, "as it tends to be where they hit first".

According to Bullman, its initial collapse in October was driven primarily by a fall-off in demand from China, where declining housing prices pushed purchasing managers to cut back on orders for the raw materials whose transport the Baltic Dry Index reflects.

He said: "This collapse looks similar to the falls we saw in the Baltic Dry ahead of the recessions of the late 1970s and early 1990s – but this drop is actually steeper."

Bullman added that it was also a more direct indicator of global economic health than government-produced statistics. "Personally, I’m not interested in employment data and GDP figures because they’re manipulated," he said. [..]

Bullman said that shipping companies have also been deliberately slowing down their journeys to save fuel, with trips from China to the US going now taking around 50% longer than they were early in 2011.

Instead, he said he was surprised by how long the Baltic Dry took to fall. The NewContex index – an indicator of prices for transporting products in container ships – started falling in April last year. Bullman said: "When we saw that happening in April, we realised that risks had returned to pre-2008 levels. We thought the Baltic Dry would start falling too, but it was actually relatively resilient."

"What this is signalling is that the world economy is slowing down much more quickly than people have been thinking."

Ilargi: The report I refer to in the title requires a little background info:

In Holland, where I'll be for a few more days, there's a "rogue" right-wing party named PVV (Party for Freedom). It has no cabinet ministers, but the minority moderate right-wing government needs its support to stay in the saddle. The PVV, like other European right-wingers, is, among many other things, against much of what the European Union stands for. It's certainly against the Euro, and the bailouts with Dutch taxpayer money of countries like Greece and Portugal.

A few months ago, the PVV announced they had commissioned a report from British financial consultancy firm Lombard Street Research on the economic consequences of staying in the Eurozone versus returning to the guilder.

That report is about to be published "within days". It will prove to be highly explosive material. And the PVV will do all it possibly can to make sure it receives a lot of media attention. It may tear down the incumbent government, which is a heavy advocate of all things Europe, and which will have to quit once the PVV support dies, but for that party that's not the no. 1 concern.

And if and when Holland has a large scale discussion on the report and the issues it raises, Germany won't be able to ignore it and stay behind. And then, neither will France.

Max Julius of Citywire.uk did a piece on the report, without mentioning it directly, 10 days ago:

Why Germans and Dutch will exit 'suicide pact' eurozone

Germany and the Netherlands are likely to quit the eurozone rather than swallow an indefinite number of 'unrequited transfers' to the union’s crisis-stricken nations, according to Charles Dumas, chief economist at Lombard Street Research.

Speaking at an event in central London, he said that before joining the single currency, German incomes had stayed level but their purchasing power had increased as the Deutschmark appreciated. With the weaker euro, the economist said, they have seen 'tremendous' wage restraint, leading to huge growth in German firms’ market share but ‘no serious growth of the economy’ and a squeeze on disposable incomes. Meanwhile, consumption rose elsewhere in the eurozone, he said.

'So what you’re actually dealing with here… is a German population which has had a rotten deal – and that’s why they’re all so angry' noted Dumas, who is also chairman of the macroeconomic forecasting consultancy. Branding the monetary union a 'suicide pact', he continued: 'So what this exercise in uniting Europe has achieved is to divide Europe.'

Dumas [noted that] the 'Club Med' nations needed about 5% of gross domestic product in annual debt refinancing 'more or less indefinitely'.

This would amount to €150 billion a year, of which Germany would have to stump up just over €60 billion, France a little under €50 billion and €15 billion from the Netherlands, he said. And this would be on top of the shortfall in consumer spending, in addition to the fact that wages and consumption may have to be held down in the future, Dumas warned.

Ilargi: This morning, Dutch daily Algemeen Dagblad cited Dumas as saying these numbers are "cautious estimates". They are valid only if Greece and Portugal would leave the Eurozone in 2012 – which Dumas expects will happen -. If they don't, the payments will be even higher.

He predicts the costs of a return to the guilder will be much less than for instance the Dutch government's Central Planning Bureau claims, which warns of huge losses if Holland were to leave the Euro.

Dumas: "It's just like in a religion: first they promise you heaven, and if that doesn't work out, they threaten you with hell."

The economist dismissed the notion that the region would be able to turn itself around so as to make such support from its 'core' unnecessary. Citing the example of the persisting transfers from west to east Germany, he pointed out: 'The ones that need the money to flow in carry on needing the money to flow in, or just stay poor.'

Dumas also warned that austerity was only worsening Greece’s budget deficit, and that it was 'difficult to imagine' the deeply indebted state receiving the four quarterly batches of financing it is due this year. ‘It’s almost impossible to imagine people continuing to stump up the money, because they simply have not actually gone into this thing with the intention of unrequited transfers to Greece ad infinitum,’ he said as the country resumed talks with its creditors over a planned debt swap.

Calling the one-off damage of splitting up the eurozone 'seriously exaggerated', Dumas warned that as the crisis deepens, he believes 'Germany and the Netherlands will actually realise that they had better call it a day and jump out.'

Ilargi: Sure, the Dutch government, and certainly the EU and the banking system, have formidable PR machineries at their disposal. We’ll see a lot of numbers being floated that contradict Lombard's report. And we'll have to wait a few days to see exactly what numbers Dumas et al. come up with.

But the people of Germany and Holland are already very nervous about the fact that they face austerity and budget cuts while billions of euros are transferred to southern Europe. Up until now, the fear of economic disaster predicted in unison by government leaders have kept them quiet. Now that a reputable economic research firm flatly contradicts these predictions, and states that, instead, it's staying within the Eurozone that will be the far more costly option, the people will grow increasingly restless.

Charles Dumas again, from Algemeen Dagblad:

"The Dutch people have lost thousands of euros in purchasing power per year since the currency was introduced."

Governments in Berlin and The Hague will have a lot of explaining to do. They have to do so against a backdrop of (near-)failing Greek debt swap talks, which will at the very least force them to admit that they have a lost tens of billions in taxpayer money to Club Med countries already.

With a second Portugal bailout waiting in the wings. And lots of negative news on Italy and Spain. And more domestic budget cuts.

They’ll realize that their governments have painted far too rosy pictures about the issues so far. And they’ll expect them to deliver more of the same. This is what we call a receding trust horizon.

It's not the report alone, it's the entire combination of factors. The report will "merely" serve as the catalyst that blows up the powder keg. It may take a few months, but it will happen. The publicity hungry rogue PVV party that commissioned it, followed by anti-Eurozone voices elsewhere, will make sure of that.

Here's another interview with Nicole, conducted by Nicholas Bawtree for Italian magazine Terra Nuova, October 2011 in Florence, Italy.

Partial transcript (thanks to John Rubino at dollarcollapse.com):

When you have economic contraction you also have a substantial contraction of the trust horizon. This deprives political institutions at the national and international level of the trust that would give them political legitimacy. They become stranded assets from a trust perspective. People no longer internalize the rules that those institutions are attempting to impose. The response is typically surveillance, coercion, and repression. This picture basically suggests that it is pointless to look for solutions from the top down. It is not solutions that will come from the top down but more problems.

So politicians typically make a bad situation worse as expensively as possible. The systems that we have established have become sclerotic and unresponsive, hostage to vested interests with no ability to adapt quickly to give people abilities to cope with rapid change. I don’t look for solutions from them. The people who are part of that system are typically the people who have gained significant amounts from the status quo. These are the last people who are likely to change things, so I don’t look for political actions.

In many parts of the world, especially in parts of Europe, people always ask me if they should take political action, change their policies at a national level to solve these problems. And I tell them unfortunately not because there isn’t any mechanism for these large bureaucratic institutions to offer anything that would realistically help, and that they‘re far more likely to try to maintain their own existence by sucking even more resources out of the periphery in order to maintain the center.

This is a bit like when a body becomes hypothermic, not enough heat. It shuts off circulation to the fingers and toes in order to preserve the body temperature of the core. That’s what we can expect politicians and political systems to do. Unfortunately for us, we are the fingers and toes and we have to look after ourselves. Nothing is coming from the top.

My solutions, such as they are, are grassroots solutions. We have to build things from the bottom up. Our centralized life support systems will fail over time because they’re critically dependent on tax revenues that won’t be there and cheap energy that won’t be there. These centralized systems won’t be able to deliver the goods and services we’ve come to rely on.

What we need are alternatives that come from the bottom up. The reason these work is because they operate within the trust horizon. They don’t have to stay small. They can grow to whatever size the trust supports and that can be different in different places. The crucial thing is that they come from the bottom up, they’re small and responsive and not bureaucratic, they make the best use of very small amounts of resources because they don’t have enormous administrative overhead.

It’s amazing what can be done at a very small scale. It wouldn’t replace what the centralized services have given us, but we can cover the basics. The key point is that we have to do it right now because we don’t have much time before we start to see centralized systems failing to deliver what they have delivered in the past. The amount of money in the system can contract very quickly. That undercuts what these centralized systems are capable of delivering in the next few years. So we must start right now building grass roots initiatives, and community is crucial to that.

We need to begin at the individual level because if we are on a solid foundation ourselves we can then help others. If we are not then our attempt to help others is fundamentally weakened. So we have to get our own house in order but then we have to think much more broadly. We must build community. Relationships of trust are the foundation of society. So we need to work with our neighbors, we need to know our neighbors and we need connections with family and community so we’re less dependent on money.

In many parts of the world where people really don’t have any money anyway, their society functions on barter and gifts, working together, exchanging skills. This works as a model. It doesn’t get you a large fancy sophisticated industrial society because it doesn’t scale up that well. But it works very well at a small scale, and this is the kind of structure that we need to rebuild.

In some parts of the world there’s a lot more of that than in other parts. So it’s actually interesting to think that it’s not necessarily the places that are the wealthiest at the moment that will do best in the future.

The analogy I use is that if you’re going to fall out of a window how much it hurts when you hit the ground depends on how many floors up you were at the time. If you were on the hundredth floor and you do nothing to prepare before you fall it’s going to be fatal. If you’re much further down it’s less painful. If you fell out of a ground floor window you might not even notice. You just pick yourself up, dust yourself off and not very much has changed.

So the places that will do best are the places where there is already a lot of trust at the foundational level, where people are used to working together, where people are not that far removed from the land. Places where there’s an enormous disconnect between resources that are available in that area and what resources that are actually used, where societies are highly atomized and used to a very high standard of living, those places will see enormous shock to the system because those people don’t have any skills or connection to land or family to fall back on.