Courtesy of Yves Smith of Naked Capitalism

Wired’s Joel Johnson has written a stunning bit of PR for Foxconn, now-controversial supplier to the consumer electronics industry, duly wrapped in credibility-enhancing guilt over Western materialism.

Wired’s Joel Johnson has written a stunning bit of PR for Foxconn, now-controversial supplier to the consumer electronics industry, duly wrapped in credibility-enhancing guilt over Western materialism.

The article, “1 Million Workers. 90 Million iPhones. 17 Suicides. Who’s to Blame?” pretends to be about Foxconn’s factories. But Johnson admits he’s a tech toy writer who apparently has no knowledge of manufacturing (I know I’ve had only limited contact with manufacturing, yet reading his piece, I’d bet serious money that I’ve seen more manufacturing operations than he has by dint of being a coated paper brat and doing due diligence on some oddball tech deals over the years, as well as visiting a motherboard maker back in the stone ages when motherboards were made in the US). Yet he’s remarkably uninhibited in using his fantasies and abject ignorance as a basis for making sweeping generalizations about the Taiwanese powerhouse. For instance:

In the part of our minds where Americans hold an image of what an Asian factory may be, there are two competing visions: fluorescent fields of chittering machines attended by clean-suited technicians, or barefoot laborers bent over long wooden tables in sweltering rooms hazed by a fog of soldering fumes.

When we buy a new electronic device, we imagine the former factory. Our little glass, metal, and plastic marvel is the height of modern technological progress; it must have been made by worker-robots (with hands like surgeon-robots)—or failing that, extremely competent human beings.

But when we think “Chinese factory,” we often imagine the latter. Some in the US—and here I should probably stop speaking in generalities and simply refer to myself—harbor a guilty suspicion that the products we buy from China, even those made for American companies, come to us at the expense of underpaid and oppressed laborers.

Huh? Is he serious about this? Anyone who has been following China even slightly would imagine Chinese factories aren’t like Japanese car-makers, heavy on robotics, but are mainly labor intensive (with the exception of some sparkling new capital intensive factories where China is trying to go up the value added chain), and if they are in the Pearl River Delta, makers of watches, clothing and toys (hence not much soldering). And if higher tech, the operations HAVE to be pretty to very clean. But no, everyone in the Wired readership is assumed to share his blinkered imagination.

This extract really does serve as a window onto the entire piece, because it is unduly involved in his inner process, and is remarkably ungrounded in reality-vetting. Yes, he did visit a Foxconn factory, on a guided tour organized and led by executives and PR giant Burson Marsteller. That fails the objectivity smell test. Did he try to talk to Foxconn workers outside the factory? Ex Foxconn workers? Apparently not. The only perspective he has outside his guided tour and his noisy imagination is from one Paul, a “steward for Western electronics companies seeking to procure components or goods from one of the city’s thousands of suppliers.” Do you think someone who makes his living connecting Western tech executives to Chinese manufacturers is going to say ANYTHING bad about the biggest fish in the electronics pond?

The piece goes to obvious lengths to soften the perception of the situation. He frames his account in terms of the suicides, when the recent New York Times series on Apple and Foxconn did not focus on those deaths, but the extreme hours and sometimes grinding physical toll (such as workers getting swollen feet from standing and working more than 24 hours straight). So the article skips almost completely over that issue, juxtaposing the seeming niceness of the clean factory he visited versus the deaths, and only very much later gets to the conditions that produced the suicides.

Johnson is quick to claim that the Foxconn suicides are one-fourth the level of that of college students. So even the most attention getting factoid is not so bad, right? Not so fast. The right comparison is not the number of suicides to Foxconn’s total workforce, since only the employees who killed themselves on site are probably the ones that are included in that total. If a worker killed themselves off site, you can be sure it would be attributed to something else (and it would be hard to parse out the causes). Moreover, it is the workers who live on site, who are about 1/4 of all employees, who are subject to the most extreme work hours (the New York Times recounts how they were roused at midnight to meet an Apple production demand). So this means the suicide rate at least as high as that of college students.

And to be apples to apples (pun intended), you’d need to compare suicides at Foxconn to suicides by college students on campus, which would presumably be more closely correlated with the stress of campus life, than of students who were simply enrolled in college. So it is very likely that a more accurate measurement would have Foxconn showing a markedly higher suicide rate than those of college students.

Finally, and I hate to be morbid, but a highly regimented, low privacy environment like Foxconn probably reduces the number of suicides below what you might otherwise observe. You have many fewer options for offing yourself available to you if you are living on site at Foxconn compared to a US college student (I am not making this up: gunshot is out, pills are probably too costly to procure, slitting your wrists actually takes proper technique). And Foxconn now has netting up to prevent jumping off most buildings and presumably also has its guard force on closer watch. That means the suicide rate probably understates the level of stress experienced by the workers who live on site.

He also bizarrely tries to bifurcate the work content, which he makes sound OK but boring, from what critics charge are more than occasional extreme hours, and completely ignores safety problems that add to the Foxconn death count, highlighted in a New York Times article at the end of January:

But the work itself isn’t inhumane—unless you consider a repetitive, exhausting, and alienating workplace over which you have no influence or authority to be inhumane. And that would pretty much describe every single manufacturing or burger-flipping job ever.

Huh? “Every single manufacturing job ever”? Some manufacturing jobs ARE inhumane. Start with the meatpacking industry in the US. But there is a lot of light manufacturing where the work is not highly repetitive, and that is also true in highly capital intensive factories like the paper industry. This “all manufacturing jobs are bad, therefore Foxconn is not so bad” is simply a baldfaced assertion.

Now I am not saying that there is not a case to be made in defense of Foxconn. But this article is an embarrassment. It’s an intellectually lazy way to assuage the guilt of Wired-reading gadget-owners. For instance, he resorts to “everyone in an advanced economy is guilty” as a way of diminishing the issues specific to Foxconn:

Every last trifle we touch and consume, right down to the paper on which this magazine is printed or the screen on which it’s displayed, is not only ephemeral but in a real sense irreplaceable. Every consumer good has a cost not borne out by its price but instead falsely bolstered by a vanishing resource economy. We squander millions of years’ worth of stored energy, stored life, from our planet to make not only things that are critical to our survival and comfort but also things that simply satisfy our innate primate desire to possess. It’s this guilt that we attempt to assuage with the hope that our consumerist culture is making life better—for ourselves, of course, but also in some lesser way for those who cannot afford to buy everything we purchase, consume, or own.

There is a huge, unexamined leap between “things critical to our survival” and those critical to what we have come to define as our comfort. It’s the unwillingness to examine the difference between the two, or any serious question raised by the role of Foxconn, that makes this piece so dubious. (And this is not an idle observation in my case. Your humble blogger fights planned obsolescence tooth and nail: I used a NeXT computer for 10 1/2 years, a TiBook for over 8, and am still using a Nokia that is probably from 2005. I am writing this post using an Apple monitor from 2002).

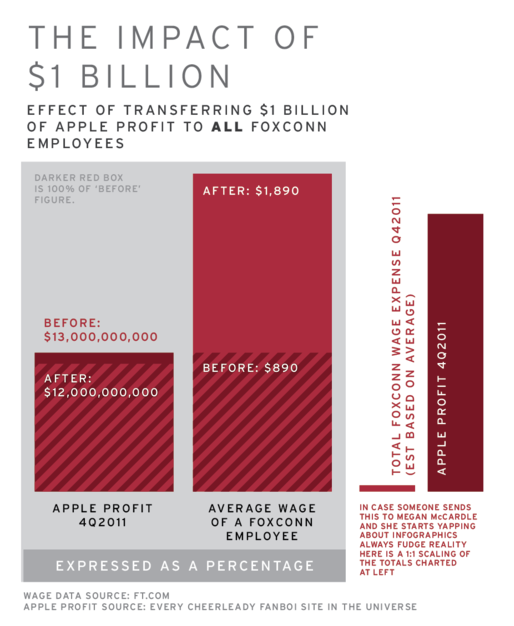

I find this little chart (hat tip Richard Smith) from ninety9 via Alea (who is the antithesis of a socialist) to be more though-provoking than the entire Wired piece:

There have been numerous articles complaining about how the Chinese don’t consume enough, and the blame is laid on the high savings rate, which is in turn attributed to the lack of social safety nets (and a second, related issue is the lack of retail infrastructure). Yet it was a sonofabitch capitalist, Henry Ford, that helped create the American middle class in 1914 by paying his workers double the prevailing rate, which partly paid for itself by reducing costly turnover and increasing productivity (well paid workers are grateful workers and want to help their company what a thought!). But the big benefit for Ford was the higher wages were in large measure met by manufacturers in other cities, and created a consumer base for Ford’s own big ticket product. It was not safety nets that created higher consumption and greater American prosperity; it was higher wages.

Ford didn’t see his pay raise as a wage increases but as profit sharing. The chart Alea highlighted shows Apple could kick start a revolution in China that would help American companies, including Apple, at comparatively little cost to itself. What stood in the way when Jobs was alive was his monumental ego and his desire to leave a legacy though his products rather than his conduct as an industrialist. And now that he is dead, Apple’s practices are likely to be guided by American short-sightedness and bad incentives for executives of public companies.