Courtesy of Charles Hugh-Smith of OfTwoMinds blog

Employment is dead in the water because opportunities for organic expansion are few and the cost basis of doing business in the U.S. keeps rising.

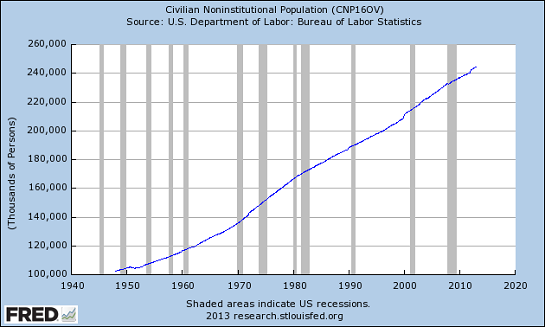

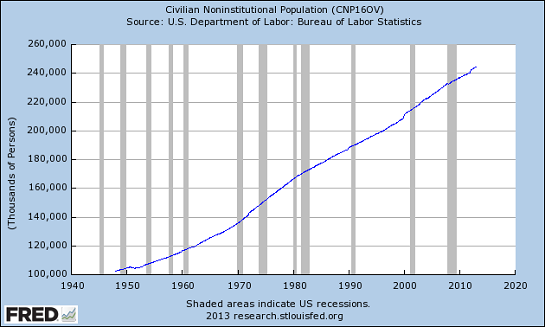

Let's start by reviewing the basics of employment in the U.S. Courtesy of the St. Louis Federal Reserve, here is the non-institutional civilian population of the U.S. (Note that the Civilian Non-institutional Population With No Disability, 16 years and over (LNU00074593)–roughly speaking, the workforce of the nation– is 215 million).

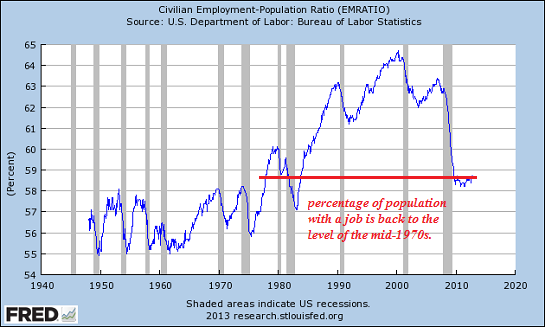

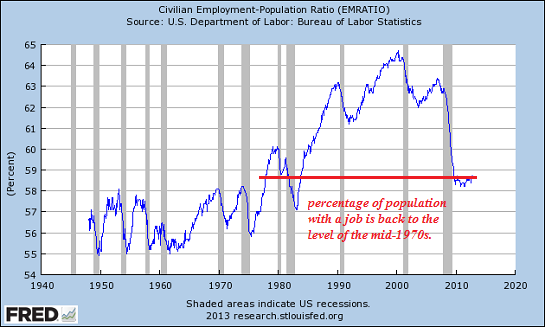

Here is the percentage of the population with some kind of job: note this could be self-employment that earns $1,000 a year or a job with 4 hours a week; recall that 38 million American workers earn less than $10,000 per year, 50 million earn less that $15,000 a year and 61 million earn less than $20,000 annually. All these numbers are drawn

directly from Social Security Administration payroll data.

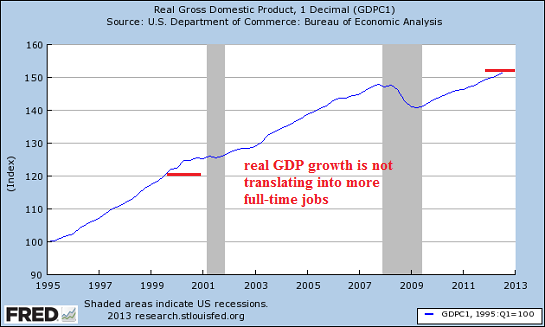

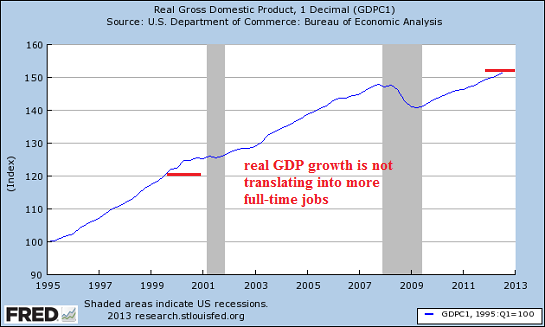

Here is real (adjusted) gross domestic product (GDP), which includes government spending. In other words, as you borrow-and-blow trillions of dollars, GDP rises.

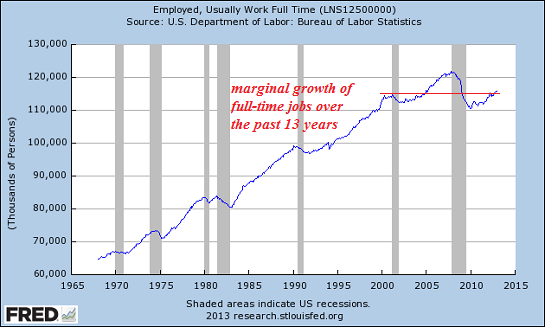

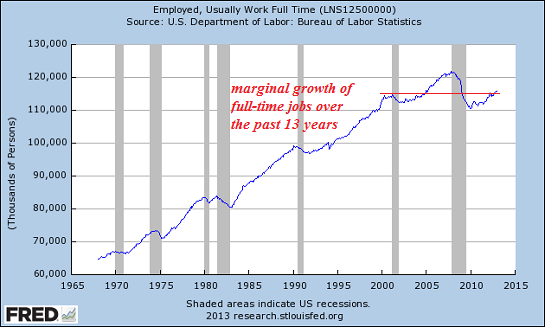

Unfortunately, employment hasn't risen along with the population or the GDP: the only metric with any meaning is full-time employment, as self-employed and part-time jobs may pay a few thousand dollars a year and should not be included in the same category as full-time jobs.

In sum: the population and GDP have both expanded smartly since 2000, but full-time employment has barely edged above levels reached 13 years ago.

Academic economists and political progressives would have us believe that the only thing restraining employers from hiring millions more people is lack of access to cheap credit.

The explicit assumption here is that cheap credit is all employers need to expand their workforce. This is so out of touch with reality that it beggars description.Progressives and academic economists generally claim the Federal Reserve's zero-interest policy (ZIRP) and its other policies of flooding the economy with liquidity "are working," i.e. boosting the economy.

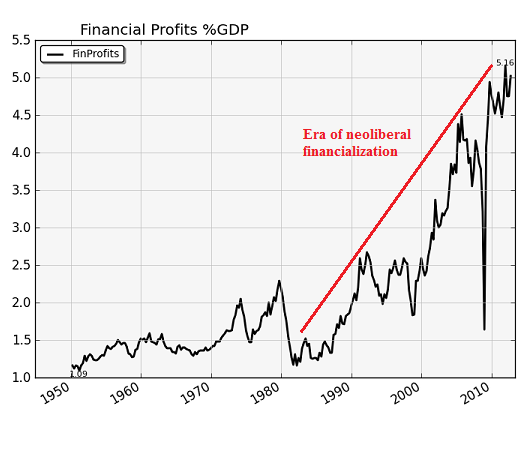

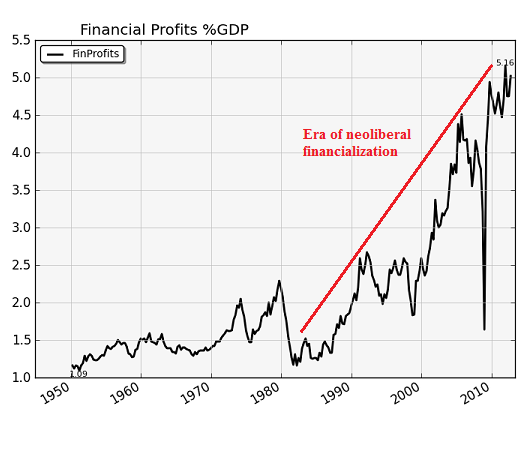

Here is what the Fed's policies are boosting: financial sector profits Please compare this chart with the chart above of full-time employment, and then decide where the Fed's free money/easy credit is flowing.

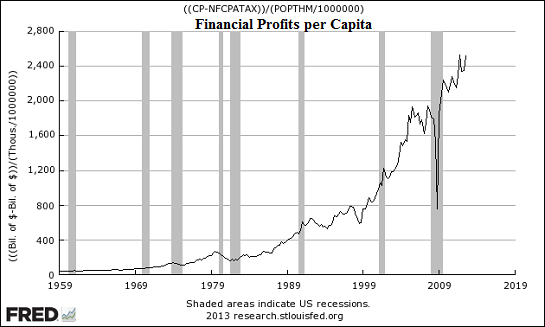

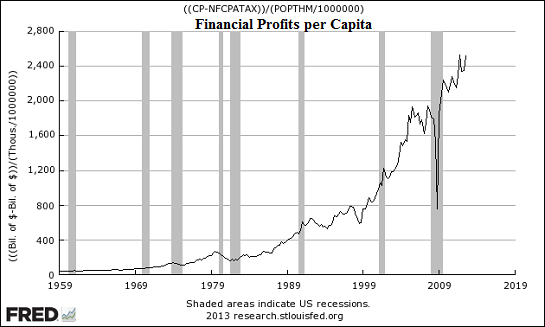

Here are financial profits per capita:

The only way to understand why employment is dead in the water is to stand in the shoes of a potential employer or entrepreneur. Remarkably, this perspective is unknown to economists and progressive politicians because they have never been an employer (and no, hiring a grad student to grade papers or an illegal nanny to watch your kids does not make you an employer.)

I have described this vast divide between small business employers, entrepreneurs and the self-employed and those working in government or Corporate America as one of the least explored social/economic divisions in the nation.

Those who have spent their careers in government or academia have little idea what it takes to hire more people. Number one is a business with strong demand for one's products or services. In a developed world with too much of everything except energy, that is no small challenge: the world is awash in over-capacity in every field except niche industries such as deepwater oil rigs.

Second, you need a process that generates so much value (specifically surplus value) that you will generate immediate profits by hiring more people.

If the value added by additional labor is low, then you have no reason to hire more employees, even if Ben Bernanke personally knocked on your door begging you to borrow a couple million dollars at low rates of interest.

If an additional unskilled worker will cost $10 an hour and might generate $100 a day in additional gross revenues, that is $20 in gross profit. But the overhead costs of operating a business are rising faster than inflation: junk fees imposed by cities, counties and states, workers compensation and disability premiums, healthcare costs (if you hire full-time workers), energy costs, and so on.

For most businesses, overhead costs 50% to 100% of total employee compensation–wages plus benefits and payroll taxes. So adding another employee to gross 20% more doesn't make it worthwhile–it actually generates a loss once overhead costs are paid.

The only time it makes sense to hire another worker is if that worker will create 100% or more surplus value from their labor. For example, a worker paid $200 a day in total compensation generates $400 more in gross revenues–enough to not only support the added overhead but net the business a profit.

In a global economy, competition constantly lowers the premium most businesses can charge. That places most businesses in the vice of declining gross margins and higher labor/ overhead costs. The only way to stay solvent is to grow revenues and slash costs so declining gross margins are still enough to pay the bills and leave some return on capital/time/risk invested.

Cheap credit doesn't create surplus value, increase gross margins or get rid of over-capacity. It is a financial non-sequitur for all but a relative handful of enterprises. The only firms interested in borrowing money for expansion are those relative few in sectors that are not burdened with overcapacity. That might include oil services, network security and a handful of others.

But high-margin sectors such as technology either get funding from venture capital or their high margins generate enough income to fuel expansion without taking on debt.

The only companies borrowing vast sums of money are those paying off higher-cost existing debt with new cheap-credit loans. The savings from lower interest payments don't flow to new hires, they flow to the bottom line and from there to executives, owners or stock buybacks that boost the portfolios of institutional owners.

Employment is dead in the water because opportunities for organic expansion are few and the cost basis of doing business in the U.S. keep rising. That vise forces businesses large and small to reduce labor costs while boosting productivity. There is no other way to stay solvent in a post-bubble, over-capacity, over-indebted consumerist economy awash in too much of everything but energy, common sense and fiscal prudence.