Courtesy of John Rubino.

Running a pension fund used to be one of the easier jobs in finance. The money came in steadily and predictably from member contributions, and you invested it conservatively (in investment grade bonds and blue chip stocks) to meet a modest annual return target of around 8%. It was cook-book money management, nice and cushy and low-stress.

But today’s pension funds have, in effect, two sets of criminally incompetent bosses making incompatible demands. At the national level the US borrows too much and lets its banks run wild, causing a debt crisis to which it responds by lowering interest rates to levels where investment-grade bonds yield next to nothing. At the state and local level, governors and mayors – loath to raise taxes or cut benefits to bring pension plans into balance – pressure funds to keep making their traditional 8% even though, with interest rates way down, that is now wildly optimistic.

So pension fund managers, forced to meet unrealistic goals in an inhospitable environment, have begun acting like hedge funds by turning to dangerous, sure-to-eventually-blow-up strategies like the this:

Pensions Bet Big With Private Equity

AUSTIN, Texas—On the 13th floor of a sleek downtown office building here, the trading desks are manned overnight. The chief investment officer favors cowboy boots made of elephant skin. And when a bet pays off, even the secretaries can be entitled to bonuses.The office’s occupant isn’t a highflying hedge fund but the Teacher Retirement System of Texas, a public pension fund with 1.3 million members including schoolteachers, bus drivers and cafeteria workers across the state.

It is a sign of the times. Numerous pension funds are still struggling to make up investment losses from the financial crisis. Rather than reduce risks in the wake of those declines, many are getting aggressive. They are loading up on private equity and other nontraditional investments that promise high, steady returns in the face of low interest rates and a volatile stock market.

The $114 billion Texas fund has hit the trend particularly hard. It now boasts some of the splashiest bets in the industry, having committed about $30 billion to private equity, real estate and other so-called alternatives since early 2008. That makes it the biggest such investor among the 10 largest U.S. public pensions, according to data provider Preqin Ltd. Those funds have an average alternatives allocation of 21%.

Including all assets, the pension’s annual return from Dec. 31, 2007, to Dec. 31, 2012, was 3.1%—better than the median preliminary return of 2.46% among large public funds, according to Wilshire Trust Universe Comparison Service.

Texas pension officials say private equity helped offset declines in its other investments. Britt Harris, the pension’s chief investment officer, says he aims to “smash” the stereotype that government pension funds are on the losing end of most investments.

In November 2011, the Texas fund made one of the largest single commitments in the private-equity industry’s history, investing $3 billion in KKR and another $3 billion in Apollo Global Management APO. Three months later, Texas teachers bought a $250 million stake in the world’s biggest hedge-fund firm, Bridgewater Associates—a first such equity stake for a U.S. public pension.

For the fiscal year ended Aug. 31, the Texas teachers fund had a 7.6% return, and pension officials say they expect their bet on alternatives can help the fund hit its 8% annual target return over the long term. Over a ten-year period ending Aug. 31, 2012, the fund has had an annual fiscal year return of 7.4%.

And this:

Money Magic: Bonds Act Like Stocks

Pension funds across the U.S. are desperate to overcome low interest rates and churn out returns big enough to pay future retirees.Now some hedge funds and money managers are pitching something they see as a Holy Grail: a strategy that often uses leverage to boost returns of bonds that usually occupy the low-risk, low-return portion of pension-fund investment portfolios.

Leverage relies on borrowing money or using derivatives to make large investments while putting up less cash. The tactic’s widespread use helped inflate the world-wide debt bubble that burst during the financial crisis, and it was blamed for ruinous losses at banks and securities firms.

But money managers such as Bridgewater Associates, the world’s largest hedge-fund firm, and a growing number of pension funds say this type of leverage is different. By using leverage through derivatives, such as bond futures, and by investing in commodities, some pension funds believe they can reduce their typically large exposure to the turbulent stock market and still earn solid returns.

Other proponents of this strategy, known as “risk parity,” include AQR Capital Management and Clifton Group, a Minneapolis-based investment firm.

Adding leverage to bonds, you can ‘lower your risk in your overall portfolio,’ Mr. Dalio says.

In Virginia, officials at the Fairfax County Employees’ Retirement System have revamped the entire $3.4 billion portfolio around a risk-parity approach. About 90% of the pension’s portfolio now is exposed to bonds, when factoring in leverage.

“We think we can improve returns while reducing the risk level of the portfolio,” says Robert Mears, the pension fund’s executive director.

Pension officials that employ risk parity say they are using a modest amount of leverage, and nowhere near what investment banks used leading up to the crisis. They also are trading in large, liquid markets, and say they have ample liquidity should they ever need to settle trading losses with cash.

Bridgewater is known as a pioneer of risk parity. Executives from the Westport, Conn., firm have pitched the idea to pension trustees across the U.S., even making a documentary-style online video about risk parity featuring founder Ray Dalio.

Pension funds and other institutional investors typically take most of their risks in the stock market. Mr. Dalio says risk parity spreads the risk to a pension’s bonds and other holdings.

“Ironically, by increasing your risk in the bonds you are going to lower your risk in your overall portfolio,” he said in an interview.

A core tenet of risk parity is that when stocks are falling, bond prices typically rise. By using leverage, bond returns can help make up for losses on stocks. Without leverage, bond returns in a typical pension portfolio of 60% stocks and 40% bonds wouldn’t be large enough to compensate for low stock returns.

Some thoughts

One of the tell-tale signs of a late-stage bubble is the ease with which tried-and-true business practices get tossed aside in favor of “innovations” that are really cons designed to maintain the deal flow. Day trading during the tech stock bubble and house flipping during the housing boom, for example, were hailed as genius at the time and revealed to be impossible (or at least too hard for amateurs) when those bubbles burst. Loading up on equities (private or public) or using leverage (inherently, unavoidably risky) to goose a portfolio of bonds simply creates a portfolio that behaves more like equities, which is to say far more erratically than bonds. Just like all go-long-the-bubble strategies, it’s brilliant while the markets are going the right way and catastrophic when they turn.

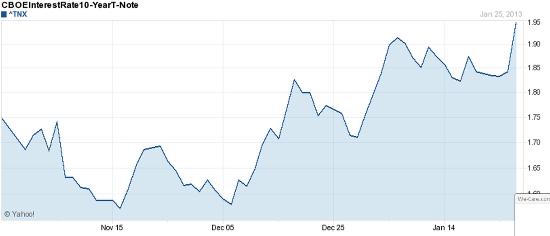

Already, interest rates are rising, which must be causing havoc with those leveraged bond portfolios.

Pension funds, because of their conservative institutional character, tend to be among the last to be pulled into the really crazy stuff, right before it all falls apart. They are, along with small retail investors, the market’s dumb money. Go back to the middle of the last decade and you’ll find stories (some of which I wrote) chronicling the innovative pension funds then loading up on alternative investments – and outperforming their peers in the short run. Most of them got creamed in 2009.

Visit John’s Dollar Collapse blog here >