Courtesy of Charles Hugh-Smith of Of Two Minds

Borrowing money to fill the gap between what we want to spend and what we generate in surplus incentivizes fraud and speculation and creates a pernicious sense of entitlement.

If things are going so great, why does our government need to borrow $1 trillion a year and our central bank create another $1 trillion a year just to keep the bloated status quo afloat? That $2 trillion a year (about 13% of the nation's gross domestic product, roughly equivalent to the entire GDP of France) is really starting to add up.

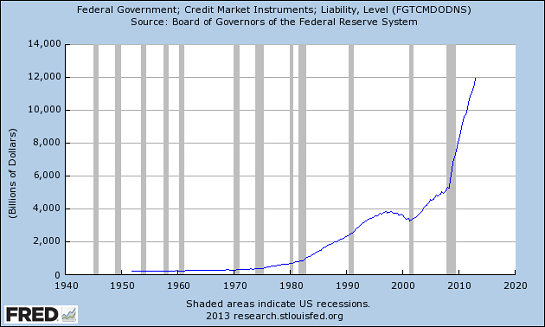

Federal debt has skyrocketed (note that this is "debt held by the public" and excludes intergovernment debt, i.e. what the Treasury owes Social Security for squandering $4 trillion in Social Security payroll taxes):

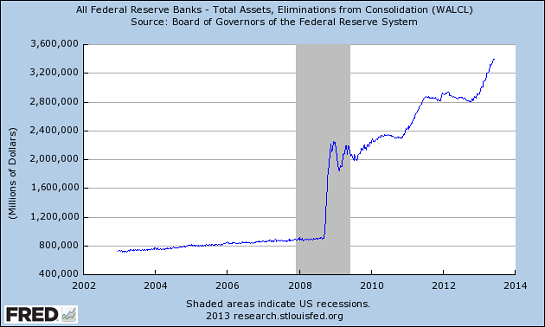

Here is the Federal Reserve's balance sheet (bonds bought with freshly created money), which has shot up with quantitative easing money-creation:

The key concept here is surplus. Surplus is what's left after you pay all costs of producing goods and services. You can only spend what's left over, i.e. surplus.

If you own an oil well and it costs $100 to extract and ship a barrel of oil, if the barrel only fetches $90 on the open market, you lose $10 per barrel. Eventually your capital is consumed and you go broke.

If you sell your output for $120/barrel, you need to set aside $10 of the $20 surplus to pay for maintenance and capital investment in the well; you can't just blow every cent of surplus, as eventually the well parts wear out and your production falls to zero.

So you can really only spend $10 of the $20 surplus per barrel.

This holds true for any good or service, for every business and every nation: no nation can spend more than it generates in surplus. the only way we can spend more than we generate in surplus is to borrow money and use the surplus to pay the interest.

As I explain in Why Things Are Falling Apart and What We Can Do About It, going into debt to spend more than you generate in surplus provides a short-term illusion of prosperity, but there is an endgame to borrowing more to live beyond your means: as you borrow more, the interest payments go up, as does the risk of default as your debt eventually exceeds your assets.

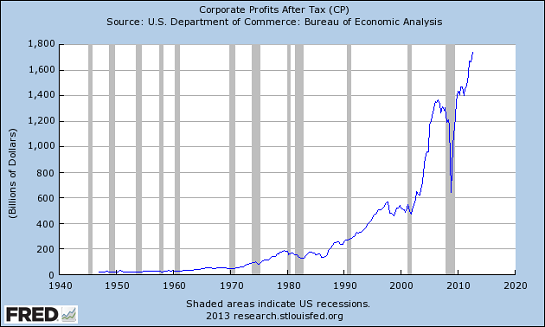

We as a nation are borrowing trillions of dollars beyond what we generate in surplus. Many commentators suggest taxing corporations and the wealthy who own most of the shares. Let's say we taxed corporate profits at around 60% and raised $1 trillion that way. By raising the $1 trillion from higher taxes, we wouldn't have to borrow the $1 trillion every year.

Setting aside the fact that corporations and the super-wealthy own the processes of governance and would never allow a 60% flat tax on corporate profits (or on the total incomes of the super-wealthy), this solution overlooks the impact on stock valuations if 60% of corporate profits are diverted to the central state to distribute as it sees fit.

The stock market would crash, of course, as valuations are based on net profits and dividends. That would wipe out not just the wealth of the super-rich but also the wealth of pension funds and insurance companies that hold stocks. Put another way: there is no free lunch. We can redistribute surplus in various ways, but redistribution does not generate more surplus.

The point here is that we can only sustainably distribute the nation's surplus that is left after capital investment. Borrowing or creating vast sums of money to paper over the fact that we're spending more than we generate in surplus fosters an entirely illusory sense of wealth and prosperity. Eventually the interest owed on debt crowds out all other spending, and the debt-based system implodes.

Borrowing money to fill the gap between what we want to spend and what we generate in surplus incentivizes fraud and speculation and creates a pernicious sense of entitlement: we can have it all, everyone can have everything they want, and there is no need for sacrifice, thrift or hard choices.

In effect, we have been leveraging our surplus into a rapidly expanding mountain of debt. That is only sustainable until interest costs start crowding out spending on politically untouchable programs and constituencies.