By Eric Tymoigne at New Economic Perspectives

The virtual currency craze is on a tear, with new virtual currencies emerging every day. The New York Times just ran a series of articles about them last week. “Charles Ponzi would be so proud!” one person appropriately commented at the bottom of this article.

Before going any further, let’s learn a bit more about the bitcoin system (also here and here). There are three components to this system:

– A unit of account—the Bitcoin (BTC)—in which all transactions are recorded and goods and services are priced.

– A payment system, supposedly secured and anonymous.

– A means of payment—bitcoins—that is needed to complete all transactions in the payment system (there are coins of several denominations and the coin with a face value of one BTC is called the “bitcoin”).

Given the craze over bitcoins, their price in US dollars (USD) has soared with a BTC 1 coin going for as much as USD 1200 at one point, leaving Business Insider’s Joe Weisenthal saying:

“At this point, I have zero idea what a ‘fair’ price for Bitcoin is.”

I have an answer to that question, but before I reveal it (pretend you did not read the title of this post), let’s spend a bit of time getting to know the Bitcoin, starting with its payment system.

All transactions that have occurred since the beginning of the bitcoin system are recorded on a ledger called the “blockchain.” The system is setup so that every ten minutes or so a new page—called a “transaction block,” or just “block”—is added to the ledger. This new page refers to all past transactions requests (by referring to the immediate previous block) and records all the new transactions requests.

The ledger is crucial to the system because it allows users to verify that a transaction request between two parties is not fraudulent. For example, Mr X. uses the bitcoin payment system to send a request to buy a pizza from Joe’s Pizza. Joe’s Pizza wants to make sure that this is a valid transaction. That requires verifying that Mr. X holds enough bitcoins to pay for the pizza (the ledger will tell from which past transactions he got his bitcoins), and that he is not trying to double spend the bitcoins. This verification process is done by the accountants of the system, who are called the “miners.” Usually Joe’s will wait for confirmation from several miners (the rule of thumb seems to be six confirmations) before agreeing to sell the pizza (“confirmation” means that a recorded transaction request is included in following blocks). Anybody can be a miner, you just need a computer.

Adding a page on the ledger is extremely difficult (more here) and requires time and CPU power. A miner can only add a page to the ledger after meeting a specific encryption requirement called the “proof of work.” The proof of work involves encrypting new transaction requests in the form of a 16-digit hexadecimal number—called “hash” or “digest”—that must be no greater than a target value set by the system. For example, to simplify, Mr. X’s transaction request with Joe’s Pizza will be combined with many other requests and encrypted as a number—say 16. But if the target value is 10, then the encryption failed to meet the requirement of the payment system, and encryption must be redone until it generates a random number below or equal to 10. This mathematical requirement is currently so difficult to satsify that it may take years for a miner using a standard computer to add a page. Indeed, the probability of finding a hexadecimal value that meets that requirement is virtually zero (3.82×10-19 last time I checked: check “Current probability of a winning a block per attempt” in “target” hyperlink above). A miner has much more chance to win the Powerball (5.71×10-9)! To speed up the process, miners can pool their CPU resources and can buy more powerful computers; however, the difficulty of adding a page to the ledger is adjusted over time to make sure that on average only one page can be added every ten minutes.

One may wonder why it is so difficult to add a page to the ledger. The main goal is to make the payment system more secure by preventing double spending of bitcoins. Another reason is to maintain the value of bitcoins by making sure that they are not put in circulation too quickly. We will come back to this second reason later and focus on the first.

If Mr. X is a miner, as an accountant he has direct access to the ledger so he may be tempted to temper it (“cook the book”). He can do so by adding to the ledger a transaction that is fraudulent in the sense that he is overspending his bitcoins (overdraft is prohibited). Given that all transaction requests are known, all other accountants could easily verify that this transaction is invalid by checking prior transactions of Mr. X. To be able to cheat the system, Mr. X has to create an entirely new (fraudulent) ledger with all past valid transactions and a new page that includes his fraudulent transaction. But he has to do it without anybody else knowing, so he has to solve a proof of work alone. In the meantime, every ten minutes a new page is created, so by the time Mr. X solves the problem many more pages will have been added to the non-fraudulent ledger. A rule in the bitcoin payment system is that accountants are only supposed to add pages to the ledger that contains the most proof of work—the “thickest” ledger (in bitcoin terminology, the accountants should add a block only to the “longest” blockchain, but the adjective “longest” is an unfortunate choice of word because what really matters is the amount of proof of work and this can result in a smaller ledger if difficulty is increased given everything else. As stated earlier difficulty is adjusted to make sure that a page is added to the ledger every 10 minutes or so in that case “longest” is an ok choice of word). So even if Mr. X succeeds in creating a new ledger that includes his transaction, all other accountants will know it is a fraudulent ledger because it won’t be the thickest. Of course all this assumes that there are only a few rogue accountants that do not pool their computer resources together to game the system by creating an invalid block in about 10 minutes.

You will notice that so far we have not described bitcoins themselves. We merely presented the architecture of a payment system with some security features. This payment system could technically use an existing unit of account (e.g., USD) and existing means of payments (one would just need to link his bank account to the payment system, like for PayPal). Is it secured and anonymous? I can’t tell you if it is safer than existing payment systems—it is not my expertise—but some past events clearly show that it is not a full-proof payment system.

Bitcoins and BTC come into the picture when one wonders how to reward the crucial work done by the miners. Being a miner, beyond being an extremely tedious activity, involves some upfront fixed costs (a computer) and some variable costs (electricity and computation time). But miners are crucial to the trustworthiness of the bitcoin payment system, so they should be rewarded. While paying miners in dollars could be done, the creator of the bitcoin payment system—who goes under the pseudonym Satoshi Nakamoto—wanted a system that runs on an independent unit of account with independent means of payment; hence the BTC and bitcoins. Each time a miner creates a new block by solving the proof of work, he currently gets 25 BTC in the form of bitcoins (over time this reward declines). The miner also receives a transaction fee paid in bitcoins. This transaction fee is provided by the persons involved in the transaction request (currently it seems to be paid by the buyer, Mr. X). The more transaction requests are included in a block, the more transaction fees will be collected by the miner who solves the proof of work.

In order to obtain bitcoins, one must first create a bitcoin wallet (or here). This wallet contains at least one bitcoin “address” or “public key” (think debit card number) with a corresponding “private key” (think debit card code). Addresses are public information but not the private key. When a miner is lucky enough to create a block, bitcoins are credited (out of thin air) to an address of his choosing. The creator of the payment system was frightened by this ex-nihilo creation of bitcoins, so he put constraints on the supply of bitcoins. The first one is the extreme difficulty to create a block, which makes sense in terms of security but also aims at creating an artificial scarcity of bitcoins. The second is that the maximum amount of bitcoins is set at BTC 21 million (at which time the reward for block creation will be BTC 0). Given the average rate of block creation (one every 10 minutes), the maximum should be reached by the year 2140. The hope is that accountants will be willing to earn their reward for creating blocks via transaction fees only.

Bitcoins can also take a physical form (or here, or here) that contains a hidden private key (think of the hidden code at the back of a gift card). These physical coins are representation of virtual coins and are funded via the income earned by the issuer of physical bitcoins. Thus, given the way they are created and used at the moment, they do not provide a means to bypass the BTC 21 million limit. They are just physical representations of virtual coins that are useful for people who are worried about leaving their private key online.

The creator of this system does not seem to see that this hard limit on bitcoin supply implies that, given transaction fees, the larger the number of transactions, the more bitcoins will go to the transaction payments and the less will be available for other purposes. One could avoid this by lowering the fee inversely with the amount of transactions, but that would reduce the incentive to be an accountant at the time when more are needed. A third possibility is for a Bitcoin deflation so that more goods and services can be bought with less bitcoins; thereby leaving more bitcoins to pay the accountants.

Okay, enough with the description. Let’s move to the analysis of the “moneyness” of bitcoins.

We are told that bitcoins are to be considered an alternative monetary instrument. Let’s take this proposition seriously and analyze it. Frankly, looking at the previous bitcoin creation mechanism, I see Easter egg hunting rather than mining. Gold only exists in a relevant quantity only in specific geological soil so you are not going to mine randomly. Mining also requires digging and here you are merely looking around for the coveted item.

It’s important to realize that block generation is […] like a lottery. Each hash basically gives you a random number between 0 and the maximum value of a 256-bit number (which is huge). If your hash is below the target, then you win. If not, you […] try again. (Here)

In addition, once you mine the gold nuggets they need much further processing before becoming coins whereas bitcoins are directly usable. But I digress.

Monetary instruments are financial instruments. Like all financial instruments, monetary instruments have anissuer who promises to do something in the future. There are one or two common promises embedded in monetary instruments. One is that they are convertible into something else, another is that the issuer will accept them as final means of payment from his debtors. Bank accounts contain both promises (conversion into cash on demand, and one can pay debts due to banks by using funds in a bank account). Federal Reserve notes currently only contain one promise, the government will take them in payment at anytime (either directly or through the banking system in case tractability and security of payments are required). Some Federal Reserve notes were convertible into gold coins in the past. Gold coins are also monetary instruments that contain only one promise, that of being accepted back by the issuer to settle debts due to him (usually a government). Gold coins have an extra feature, they are collateralized by the value of the gold content. Note that the gold content of the coin is not a monetary instrument, and it is not what makes the coin a monetary instrument. Gold bullions were never financial instruments (they contain no promise), they are real assets, i.e. commodities (payments made with them are payments in-kind).

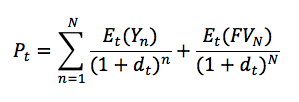

Given the nature of monetary instruments, they have also other characteristics common to all financial instruments. First, all financial instruments are accounting creatures. They are the asset of the bearer and the liability of the issuer. Gold coins were the liability of, e.g., the King, Federal Reserve notes are liability of the Federal Reserve, and coins are the liability of the Treasury. Currency is their liability because they (at least) promise to take their currency from bearers in payments at any time; issuers owe that to the bearers. That is partly how their scarcity is controlled. Second, all financial instruments have a fair value that is defined as the discount value of future streams of monetary payments.

Where the subscript t indicates the present time, Pt is the current fair value, Yn is the income at a future time n, FVNis the face value that will prevail at maturity, Et indicates current expectations about income and face value, dt is the current discount rate imposed by bearers, N is the time lapse until maturity (n = 0 is the issuance time). There is a wide variety of financial instruments using that formula. On one extreme are modern monetary instruments that, provide no income (Y = 0), have an instantaneous maturity (N = 0), and are widely expected to be taken back by their issuers at their initial face value at any time, Pt = FV0. On the other extreme are stocks and consols that have a positive expected income and an infinite maturity, Pt = Et(Y)/dt.

Given that bitcoins are supposed to be monetary instruments, they must follow the preceding basic rules of finance. We clearly know who the bearers are (the lucky Easter egg hunters and the persons to whom they get sold) but who is the issuer? In other words who put the eggs in the forest and is willing to accept them in payments due to him or her. I can tell you the answer for Easter eggs: none of the persons who put them in the forest promised to accept them in payments. Therefore, they are not a liability, therefore they are not a financial asset, and therefore, they are not monetary instruments. They are real assets, commodities. The same applies to bitcoins. There are commodities and people are basically involved in trading a commodity on a world scale; with much of the craze coming from China (see here for a link to world map of current bitcoins transactions). Think of international bilateral trade of Easter eggs for other commodities; it is barter on a grand scale (remember people in the past who would sell their farm for a tulip…).

We just established that bitcoins are not financial instrument, but let us, for the sake of argument, continue to assume that they are. This means that they must have a fair value. Now what is the fair value of a bitcoin? It does not provide any income (Y = 0), it has no maturity given that it is not a financial instrument. For the sake of argument, we might assume that their maturity is infinite because we are stuck with them forever once they are created. So their fair value as financial instrument is…A BIG FAT ZERO (you can use whatever unit of account you want). A BTC 1 coin should circulate at a 100% discount (BTC 0) if it was a monetary instrument, which means of course that it would not pass hands.

This would have been different if there had been an issuer who took back bitcoins at face value in payments. As bitcoins would have come back to the issuer, they would have been destroyed (like any pizza restaurant destroys free-pizza coupons that are returned to make sure they are not stolen and reused to get another pizza). Unfortunately, nobody issued them (and they are not edible like Easter eggs) and so we are stuck with them. This was actually a mistake made throughout history. Kings would issue coins and never promise to take back them in payment! Private banks issued notes that they would not accept in payments! Fair value fell and coins would disappear as people melted them down to extract the gold and sell it as bullion. Bitcoins have not intrinsic value so their fair value would dropped to zero.

The supply of monetary instruments needs to be elastic enough to change with the demand for them. They should be easy to create (bitcoins are) BUT ALSO easy to destroy if demand declines; that maintains the scarcity of the monetary instruments while making them responsive to the needs of the economy. Bitcoin supply fails on both sides, it is not demand driven; it is exogenous.

Currently, the only things that give bitcoins value as commodities is their utility and their scarcity. People love the beauty, spiritual meaning, and taste of Easter eggs and so are willing to pay for them. Is there anything to love about bitcoins? People involved in illegal activities and money laundering, who have a phobia of Big Brother or who just hate the federal government, find utility in this means of payment because bitcoins allow to access the anonymous payment system. Other people who loves gambling also find utility in bitcoins. Both categories of people will be willing to pay top dollar for them given their scarcity.

One may note that what gives value to bitcoins is not that there are redeemable in dollars. They are not redeemable (their quantity can’t be reduced by converting them into something else). What gives them value is that people are willing to pay a lot of dollars for them (or tulips if you see where I am going with this: people are trading virtual tulips that grow out of thin air and never die).

The structure of the payment system, not bitcoins, is actually what makes the bitcoin project so successful. It is supposedly so secretive that you can trade a bunch of illegal stuff and evade taxes. Think Easter eggs (or tulips) for coke, Easter eggs for guns, Easter eggs for prostitutes, the sky is the limit and everything is priced in an Easter egg unit of account (EE). A pound of coke EE1000. Of course, there is a slippery slope. You can write contracts in a EE unit of account that promise to deliver Easter eggs, you can securitize these contracts, you can write contracts that bet on when the supply of Easter eggs will exactly run out. Heck! You can write any contract you want because there is no regulation. Contracts can have the most stupid (and hidden) clauses in them as long as someone will swallow them in expectation of huge returns. (You did not know? They love Easter eggs on Mars!)

So there is a fixed supply of a commodity and a demand for that commodity (is it downward sloping? Probably not because speculation can easily overwhelm the use of bitcoins as anonymous payment method). A perfectly inelastic supply curve with a volatile demand curve is a recipe for wide price fluctuations of bitcoins in USD. If one takes chapter 17 of the General Theory, the bitcoin is an asset with no income (q = 0), no liquidity premium (l = 0), some carrying cost (c > 0, because one needs a computer and electricity to use them, even if in physical forms), and an expected capital gain or loss (a < > 0), so their expected rate of return is:

Rbc = abc – cbc

Put simply, Bitcoins are purely speculative assets. There are websites that help calculate if mining bitcoins is expected to be profitable, but, as one website notes: “Extrapolating bitcoin difficulty or price is pure voodoo.”

Happy searching! You could make a lot of money in dollars by speculating on Easter egg value (you won’t get rich as an Easter egg picker, i.e. miner)! But don’t get lost in the woods! By the way, just for full disclosure, those who organized the hunt collected a bunch of eggs before the forest opened to the public. They made a killing as many people were waiting for them when they came out of the forest to buy the eggs at a steep dollar price. After all, who wants to go into this stinky wet forest…just give me the dammed eggs so I can go watch TV…or sell my drugs and guns, hopefully in total anonymity and security.

*Footnote: Is all this consistent with MMT? Yes. MMT does not state that all monetary instruments are government issued or that every unit of account must have its origin in a government declaration. Monetary instruments can be created by anybody but their capacity to be widely used will vary with the capacity of the issuer to make others (willingly or forcefully) indebted to him. The state usually determines the major unit of account used and what the legal tender is but anyone can issue promises and use any unit of account they want (Easter Egg, Buckaroo, etc.).

Original article posted at New Economic Perspectives