Courtesy of The Automatic Earth.

Arnold Genthe “Diamond antique store, Royal Street, New Orleans” 1920

An interesting government commissioned report came out yesterday in Britain, prepared by a commission under oil veteran Sir Ian Wood, and dealing with the prickly issue of what to do with the fast dwindling oil and gas production – and tax revenue – that comes from the British North Sea patch. What probably “worries” the government most of all at this point is that the oil and gas industry is threatening to leave any further investment and exploration alone because it is no longer – sufficiently – profitable.

Sir Ian therefore proposes/demands the government should invest, and make North Sea exploration profitable once again for Big Oil. Which has made huge profits on the exploitation for many years but never provisioned for re-investing those profits in leaner times, even though they always knew such times would come. No, as soon as the big profits stop, it’s up to the taxpayer to come up with the cash, that is if (s)he wishes to keep her feet warm and dry. Let’s all sing the praises of the free market, while the market itself sings the praises of industry friendly governments and their pockets filled with tax revenues.

Of course, it’s easy to say in hindsight, but shouldn’t a contract have been drawn right at the start to cover the entire exploitation process and timeframe, forcing oil companies to reserve early profits to make sure no assets would be left unnecessarily stranded, without that costing taxpayers even more money at the end of the line? Guess that would have spoiled the party.

A few details from the article:

• North Sea oil industry needs ‘urgent’ government help; exploration at all-time low (Telegraph)

North Sea oil exploration is at a “worrying” all-time low and needs urgent government action such as tax breaks to stimulate drilling, Sir Ian Wood has warned. In a government-commissioned report, the industry veteran said that up to 16 billion barrels of oil could be left untapped in the ground if exploration remained at current low rates. He also warned the North Sea would continue to see steep declines in oil and gas output unless government and industry tackled a series of problems, including falling productivity and rising costs.

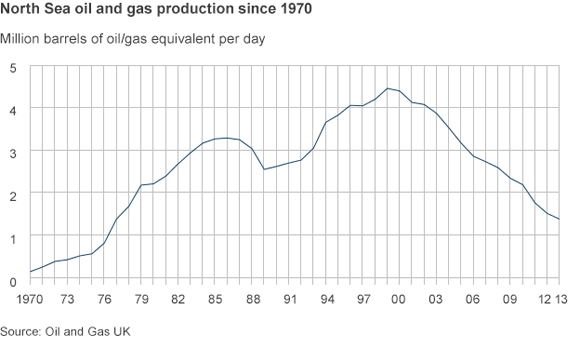

Production in the region has fallen by 38% over the last three years and hit a low of 1.4 million barrels of oil and gas last year. Investment levels would halve in the latter part of the decade from last year’s record £14 billion, unless significant new discoveries or developments are made, he said. Ed Davey, the energy secretary, vowed to implement Sir Ian’s recommendations, which include creating a new North Sea regulator to drive collaboration between energy companies. [..]

[..] … the industry believed “the fiscal regime failed to provide sufficient incentive to explore”. He said there was a “fundamental view” in the industry that the 62% tax rate for new oil and gas fields was “too high” [..]

Other issues highlighted by the report included a slump in productivity, to 60% efficiency from 70% in 2010, costing the UK economy £6 billion.

A 12-13% annual drop in production is certainly nothing to sneeze at. And you got to love terminology like a “fundamental view”in the industry that tax rates are too high. These guys know spin in a way that few politicians do.

In December 2013, a preliminary draft of the report was released, and our dear friend Euan Mearns, Honorary Research Fellow at the University of Aberdeen, wrote about it at the time in Compel firms to extract North Sea oil in the nation’s interest . Euan has some more numbers – and graphs – to enhance the picture. According to Euan:

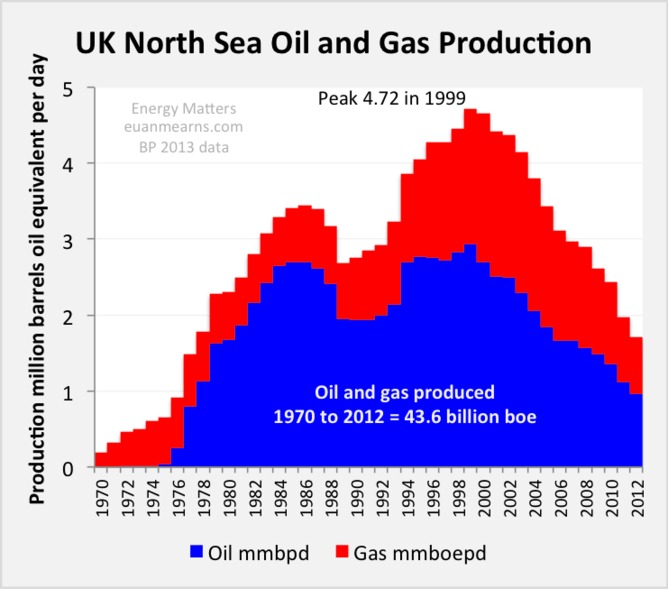

• UK North Sea oil and gas production peaked at the equivalent of 4.72 million barrels per day (of oil equivalent) in 1999 and has been in an accelerating decline since.

• These days the UK is a net importer of oil and gas, and coal, accounting for £22 billion of the £59.8 billion deficit in the 2012 balance of payments.

• 43.6 billion barrels of oil equivalent (based on BP’s conversion ratio of 1 billion cubic metres of gas = 6.6m barrels of oil) have been produced so far, with max 10 billion barrels left.

Let’s catch that in a few graphs. First, Euan’s own graph on total production:

Which in a smoother version looks like this:

The Economist added a nice detail in 2012: cumulative decommissioning costs. Wonder who’s going to pay those.

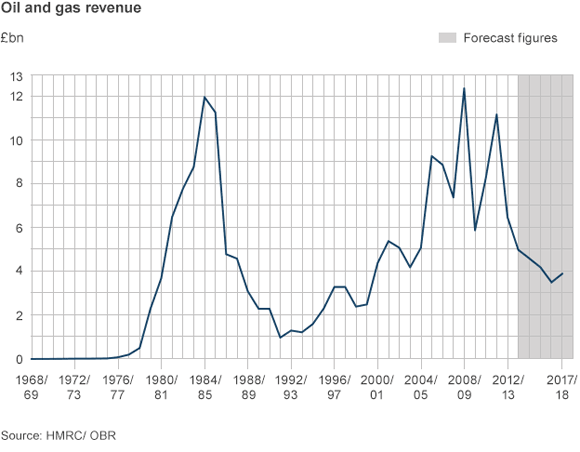

The picture for UK government income has of course changed drastically since the 1999 production peak.

Looking at this, you can’t help wondering to what extent successive British governments have ensured adequate reserves and provisions for such a development (which was entirely foreseeable, but may still not have been foreseen). Because here’s the consequence of being forced to shift from exports to imports: it hits hard, and it’s irreversible.

A few more words from Euan Mearns, which leave some room for questions:

The interim report suggests there is the potential to extract at least 3 to 4 billion barrels of oil more than would otherwise be recovered, worth around £200 billion to the UK’s economy at today’s prices. One of my main criticisms of the report is that it does not define what “would otherwise be recovered” actually means.

I have suggested that UK Oil and Gas Reserves would produce about 4.5 billion barrels at current extraction rates, similar to proven reserves reported by DECC and BP. So “3-4 billion more” would mean around 8.5 billion barrels if Sir Ian’s recommendations were to be implemented, totalling perhaps 10 billion if we reasonably allow a further 1-2 billion more in reserves yet to be found. There will be one or two undiscovered giant fields lurking out there somewhere.

Sir Ian is explicit about where this additional oil comes from, naming enhanced oil recovery (1-6.5 billion in best case scenario), increased exploration (1-1.5 billion), better use of infrastructure (0.5-2 billion), and postponing decommissioning by five years (1 billion). But Sir Ian also estimates “a further 12-24 billion” barrels, without giving any reference or figures. If state regulation of the North Sea and operating practises of the companies are to be overhauled then there must be a means for measuring the effectiveness of Sir Ian’s changes. [..]

Enhanced oil recovery is necessary to retrieve the remnants of oil from mature fields. The bulk of the oil is left behind as micro-droplets either stuck to mineral grains or encased by water in rock pores. A variety of chemical methods can be used to get this oil moving up to the surface. For example, BP injects methane gas in the Magnus Field, and is proposing to inject fresh, as opposed to salt, water in their west of Shetland fields. Potentially the greatest reward comes from injecting CO2. In my opinion, the government would do well to divert its attention from carbon capture and storage to using CO2 for enhanced oil recovery.

As for as yet to be recovered oil and gas, let’s make clear first of all that it’ll be far less than what has already been won. Euan doesn’t seem to be willing to go beyond 10 million barrels, while Sir Ian throws out “a further 12-24 billion” barrels without reference, but that is probably from the Department of Energy and Climate Change (DECC), a number the Economist also quoted could be produced over the next 30 years.

But by then the government would be paying most of the costs, while exports would need to rise hugely only to run in place. But whenever someone talks about something that’s supposed to happen 30 years from now, credibility wanes with the years.

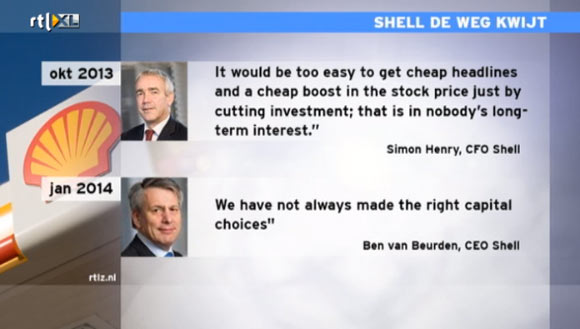

I came to think of all this because I saw an item on Dutch business TV channel RTLZ this morning about Royal Dutch Shell, which I haven’t found back in the English language press, so I’ll walk you through it:

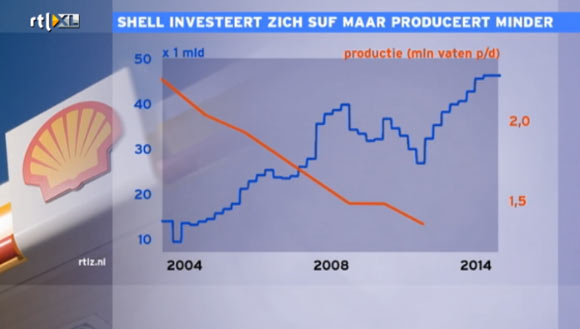

They talked about Shell and its present set of problems, and that particualr set appeared to me to be very much like the UK North Sea situation, only with a sort of extra twist. First, Shell production has fallen off a cliff. And that’s despite investments having gone through the roof and beyond.

Blue=investment (I assume in €), orange=production (in Mbd).

You see that investments went, in just 10 years time, from €10 billion to €45+ billion. While production has fallen even much steeper than the UK North Sea patch, they lost 2/3 of production from 2004 to 2011. In my humble view, that’s insane!

The picture painted from investors changed even faster:

Granted, the new CEO only came in on January 1, but there’s a major shift they’re making, if not to say a bombshell (pun intended).

Shell has decided to wind down its investments. It has figured out that no matter how much capital it was throwing at the wall, nothing stuck anymore.

In 2015, Shell will pay more in dividend than it generates in cash!

And while that can be seen as simply a business decision, or even merely a way to make investors happy, you do have to wonder what the future holds for what has been one of the biggest global companies for a long time – and for its investors -.

Here are a few details:

• Shell to cut investments by 20% in 2014

• They put their Alaska projects “in the freezer”, at a cost of €5 billion

• They quit a gas-to-liquids (i.e. diesel) plant in Louisiana

• – from last year – Shell wrote down €2 billion in US shale assets (not sit on them for a while, or try to sell them, just write off as a clean loss)

Moreover, Shell is urged to keep out of the Arctic too by principled investors. So where should the company turn to make a buck?

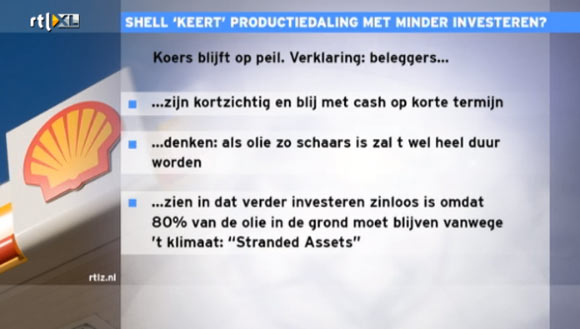

The RTLZ guys were asking why Shell’s shares price didn’t plummet when this became known, and they had a few interesting suggestions:

• Investors are short sighted and happy with a bit of cash in hand

• Investors think that if oil is that scarce, prices will soon surge

• Investors see that climate rules will force 80% of remaining oil to stay in the ground as stranded assets.

Here’s the video, if you like a foreign language.

Now, I don’t know about you, but when I go through numbers and data this way for a few hours, I get a queasy feeling that maybe things are not nearly as positive as we are made to think (or should I say even worse than we already figured), and not just decades from now, but in the near future. If a company like Shell essentially starts to wind down its core business, in the sense that business has been focused to a large extent on exploring as much as producing, what does that mean? Investors may hold on to shares a while longer because they’ve been promised large(r) dividends, but why hold on after that?

And of course, as Shell goes, so do Exxon and BP and all the other former greats. And with them the carbon that built our world. It wasn’t just carbon, it was increasing amounts of it. And cheap. Here’s thinking that over the next decade, or two, you’re going to be keeping your oil company alive in the same exact way, and for the same exact reasons, that you keep your bank alive. And the lifestyles of its executives.