How Inequality Drags on the Economy

Courtesy of Joshua M Brown

GMO’s James Montier is out with a landmark white paper on the destructive nature of Shareholder Value Maximization (SVM) when taken past the point of economic utility and into the current stratospheric extremes. Generally speaking, SVM has fostered a corporate culture in which C-suite executives focus on short-term benchmarks (or get fired), eschew investment in the future (so as to hit said benchmarks) and are compensated to the point where the top 10% of income owners end up controlling 80% of the stock market and over 100% of aggregate income growth.

It’s a f***ed up situation and has been a direct cause of the record inequality that has been so relentlessly documented in the post-crisis period. Shareholder value maximization for today should be practiced in an equilibrium with what might be best for tomorrow and the next day. The trouble is, how do you convince everyone to act a certain way when they’re being incentivized so strongly in a different direction? If Bezos and Amazon are at one end of the spectrum and the hollowed-out private equity shell that is Burger King is at the other, how do we agree on where the optimal locale on the curve is for every other company? I don’t think these are questions that can be answered very easily and there probably isn’t a one-size-fits all approach here for all industries.

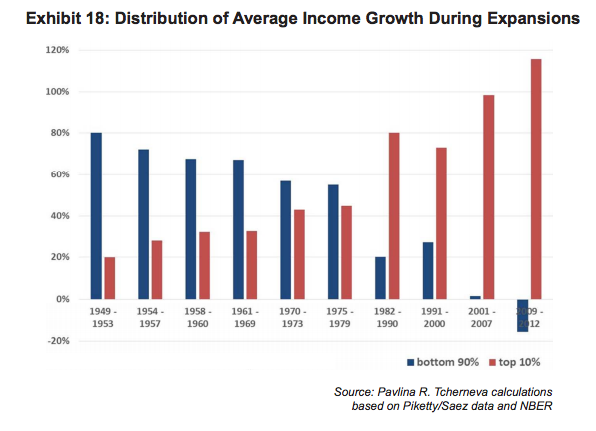

Montier posts a chart that goes a long way to illustrate the effect that SVM has had on the economy itself. When the top 10% accrues all of the benefit (or more than all of the benefit) of an economic recovery, the economy doesn’t quite recover all the way in real terms. This is because the 90% that are not seeing their incomes grow are the people who would be most likely to spend their additional money while the 10% are more likely to save it or send it back to the stock market.

If one looks at the income gains during expansions as Pavlina Tcherneva (2014) has done, one will find that during the last two expansions the income gains have gone entirely (and most recently more than entirely) to the top 10%.

The problem with this (apart from being an affront to any sense of fairness) is that the 90% have a much higher propensity to consume than the top 10%. Thus as income (and wealth) is concentrated in the hands of fewer and fewer, growth is likely to slow significantly.

It’s hard to see how the economic recovery truly lives up to its historic potential until the average income growth evens out a bit. The first few years of recovery had been hilariously lopsided and the resultant sluggishness of overall recovery in absolute terms (never mind in relative terms versus the stock market) played out exactly as it should have – the people we needed to start spending simply could not.

The good news is that wage growth is starting to spread out a bit more, as Friday’s November NFP release told us. It’s a little bit of an improvement – but more would be better.

Read the full Montier paper at the link below.

Source:

The World’s Dumbest Idea

GMO – December 2014