A glut of oil?

Courtesy of James Hamilton of Econbrowser

The world is awash in oil, I’m hearing. The problem is, it’s fairly expensive oil.

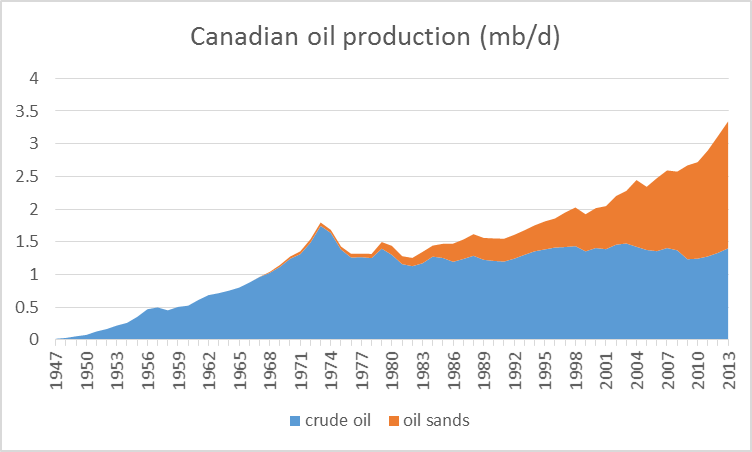

Take for example Canada. The country has managed to increase its production of oil by a million barrels a day over the last decade. But almost all of that increase has come from oil sands. If you consider only conventional crude oil, Canadian production today would be a third of a million barrels a day lower than at its peak in 1973.

Canadian production of crude oil, 1947-2013, in mb/d. Blue: Conventional crude plus lease condensate. Orange: oil sands. Data source: Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers.

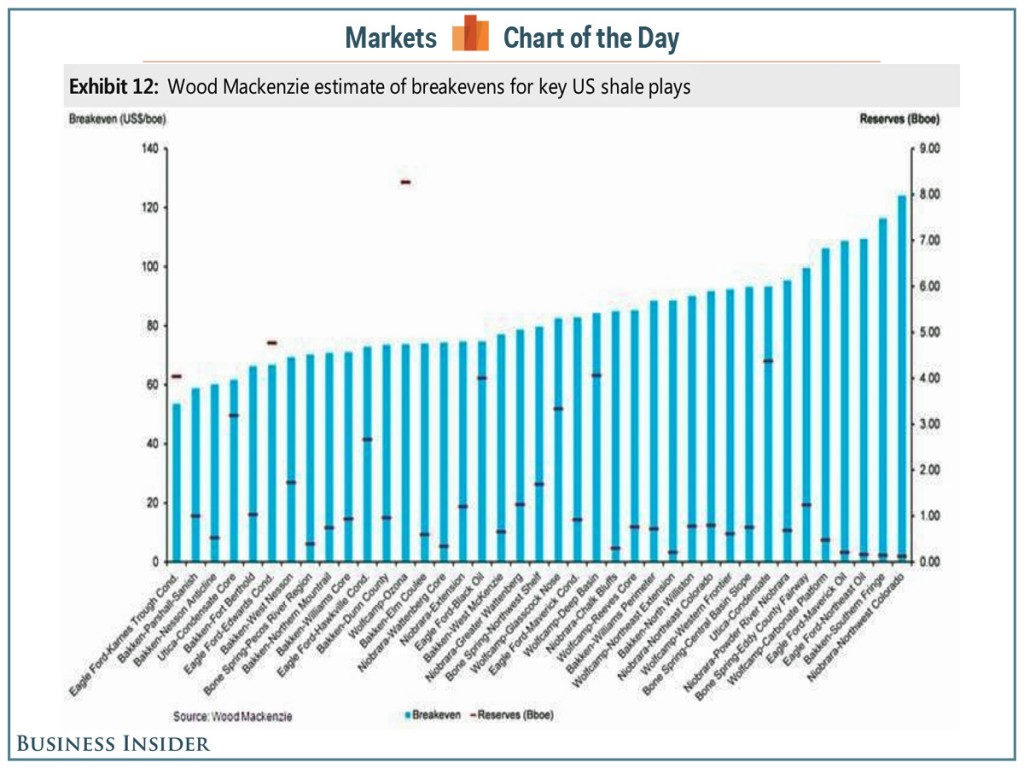

Even without counting environmental costs, that stuff’s not cheap. It was profitable when West Texas Intermediate was over $90. But last week WTI closed at $66. Here are some of the estimates from the Wall Street Journal:

The break-even price for new oil-sands surface mines is among the most expensive in the world, at around $85 a barrel, according to Bank of Nova Scotia . Operating costs at existing mines are less than half that amount. But the break-even point for so-called in situ projects, in which bitumen is heated and pumped up to the surface, range between $40 a barrel and $80 a barrel. Such projects represent the majority of future growth.

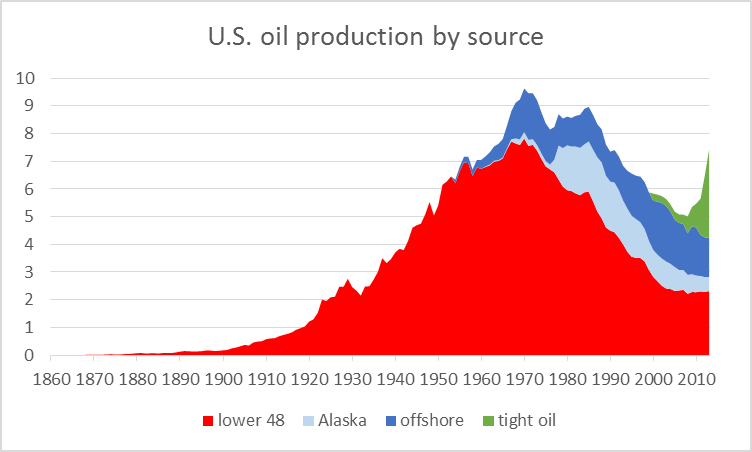

Or consider the United States, where production has grown 2 mb/d since 2004. More than 3 mb/d of that growth has come from fracking of oil trapped in tight geologic formations. Without tight oil, U.S. production would be down more than a million barrels a day over the last ten years and down 5-1/2 mb/d from its peak in 1970.

U.S. field production of crude oil, by source, 1860-2013, in millions of barrels per day. Source: Hamilton (2014).

Estimates again vary, but prices this low have to severely inhibit new investment in U.S. tight oil. Without continuing new drilling, U.S, tight oil production would quickly fall. And the economics of deep ocean drilling, which has also been important in supporting production in the U.S. and around the world, have become even more difficult at today’s low prices.

Source: Business Insider.

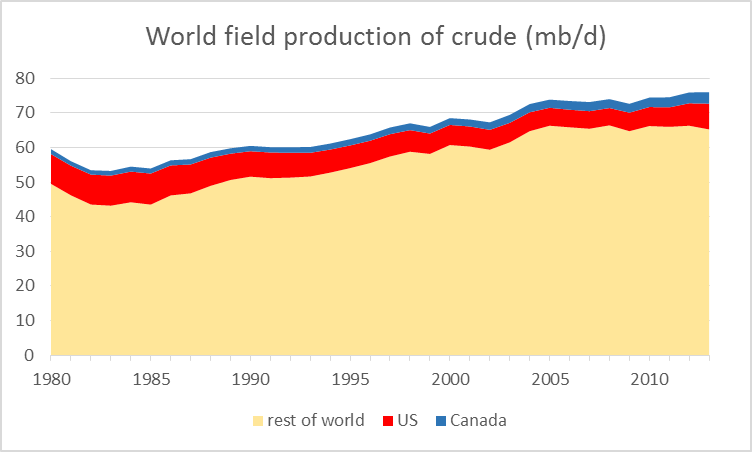

Why am I talking about the costs for Canadian and U.S. oil producers? Because if it had not been for the success of Canada and the United States, world production of crude oil would be down overall over the last decade.

World field production of crude oil and lease condensate, 1980-2013, in millions of barrels per day. Data source: EIA.

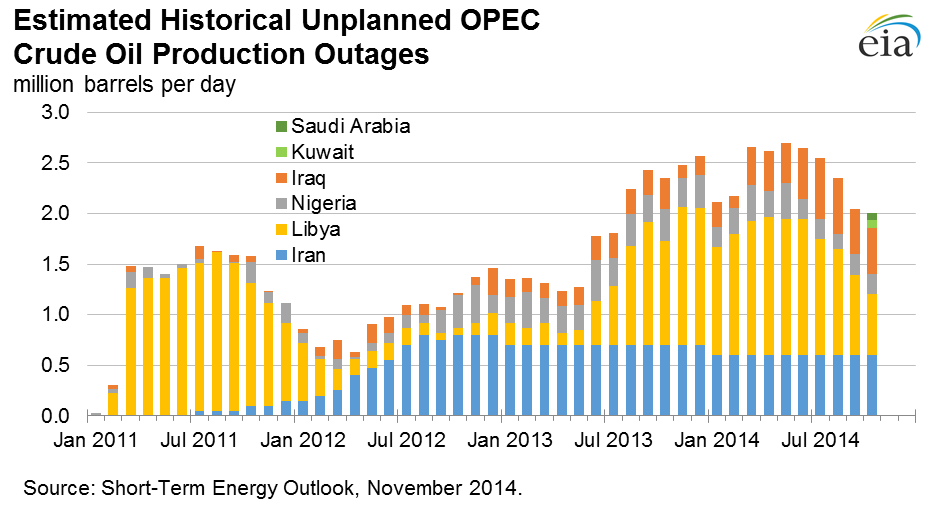

Granted, some of the stagnation in global output has been due to geopolitical disruptions, Libya being the most important example. And Libyan production rebounded significantly this fall, contributing to the current excess supply.

Source: EIA.

But Libya remains a very unstable place. It does not take much imagination to see the recent gains there being reversed again over the next few months. Nor does one have to be an excessive worrier to be concerned about the possibility of geopolitical turbulence in places like Nigeria and Iraq taking out more of their production, which between them accounted for 5.4 mb/d of last year’s world oil supply.

So here’s the basic picture. The current surplus of oil was brought about primarily by the success of unconventional oil production in North America, most new investments in which are not sustainable at current prices. Without that production, the price of oil could not remain at current levels. It’s just a matter of how long it takes for the high-cost North American producers to cut back in response to current incentives. And when they do, the price has to go back up.

Here’s my advice to anybody who’s contemplating selling $85 oil at $66 a barrel– don’t do it. If you can wait a few years, that $85 oil will be worth more than it costs to produce. But selling it at a loss in the current market is a fool’s game.