Regulators Are Getting Worried About their Own Handiwork

Readers may recall a remark we made when we discussed the dangerous boom in low grade corporate debt. This was in connection with one of the weak links in the chain, if you will. We noted among other things in passing that:

“…new regulations have forced the banks to vastly reduce their proprietary trading activities. They have essentially withdrawn from the function of “market makers” in these securities.”

The question we pondered was actually whether banks, by virtue of having removed themselves from a lot of proprietary trading and market making, would be less exposed to a putative credit crisis as a result. Certainly it could be argued that the growth in excess reserves has made banks far less vulnerable to “bank run” type situations, but as we pointed out, one cannot simply ignore the interconnectedness of financial markets. In this particular case, other entities have intensified their trading activities, and these others receive funding from banks. In essence, some types of risk are now merely one step removed, but they have not disappeared.

However, there is another reason why the above should be seen as potentially quite worrisome. That is the fact that the new regulatory hurdles leave certain market segments – especially corporate bond markets – far less liquid than they once used to be. We were reminded of this when Bill Fleckenstein mentioned in a missive a few weeks ago that one of his contacts in the fixed income trading universe had warned of the risks posed by mutual funds investing in various grades of corporate debt (and we presume, by extension, other funds active in these areas, as well as certain ETFs). The specific worry expressed by this investor was that if these funds were ever hit by a wave of redemptions, they would be forced to sell into what would essentially be a vacuum.

It appears regulators have woken up to the problem, which is often a sign that we have passed the point of no return quite some time ago (as they are often the last ones to notice a problem, even if they have caused it themselves):

“Global financial regulators worry that banks are scaling back costly market making functions and that this could leave investors stranded, as well as squeezing funds to drive economic recovery, a senior official said on Tuesday.

Some banks have already warned that tougher rules designed to make the financial system safer since the crisis of 2008-2009 have pushed up the cost of market making, or providing facilities for investors to buy and sell shares, bonds and derivatives.

David Wright, secretary general of the International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO), which groups market regulators like the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission and Germany’s Bafin, said it was an issue that was being looked at.

“It’s a concern. I think this is at the research stage,” Wright told Reuters on the sidelines of a conference, the fear being that thinner liquidity will lead to markets freezing up when they come under stress, leaving investors with nowhere to go.

“We have seen a ‘Houdini’ disappearance of market makers in general,” Wright added. “First of all we have got to establish the facts, look at the markets … and see if this is a big problem … It’s a new frontier-type issue. I think it’s partly caused by some regulation, but we need to know.”

Researchers at the Financial Stability Board (FSB), which coordinates regulation in the Group of 20 countries (G20), have already raised the issue, Wright noted. Richard Semark, a senior executive at UBS UBSN.VX who deals with European client trading requirements, told Reuters that shrinking liquidity is an issue in Europe’s fixed income market, because new rules make it more expensive for banks to hold the inventory of bonds needed for market making.

New European Union rules will also effectively ban off-exchange trading of shares among banks and big investors, Semark said. “It seems as though in Europe that almost from every angle liquidity is being squeezed.”

Banks have also warned that market making could take a further dent if the EU goes ahead with a measure to isolate risky trading at banks. However the European Central Bank has already acknowledged bank structural reform measures need tweaking to avoid harming market making.”

Now that sure leaves one with a warm, fuzzy feeling. Never fear! Regulators are on the case! As in: “It’s a concern. I think this is at the research stage… a ‘Houdini’ disappearance of market makers…I think it’s partly caused by some regulation, but we need to know.”

You couldn’t make this up.

Mind, we have no intention of offering any “better plans” or telling anyone how the tens of thousands of pages in new financial regulations that have been dreamed up since 2008 should be “tweaked” to improve this situation. We merely want to let readers know what we believe to be the weak links in the current bubble era.

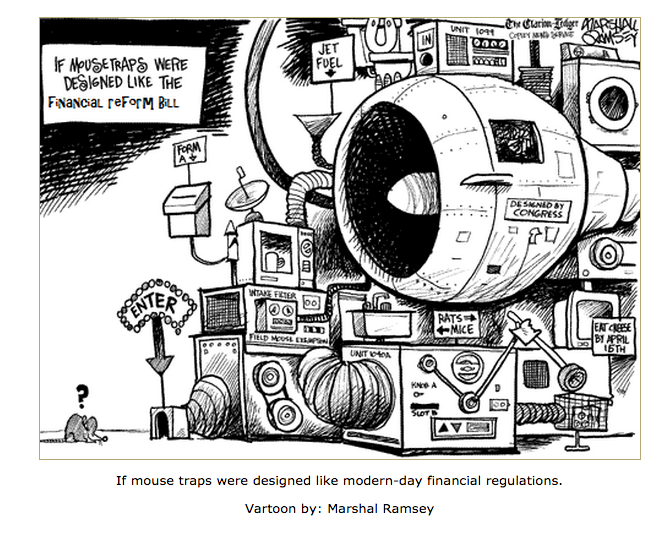

The regulations governing a free banking system in a truly unhampered market economy would fit on half a napkin. Tinkering with monstrosities like Frank-Dodd is completely futile. As we have previously pointed out, the increase in complexity these new regulations have brought about practically ensures that the system has becomeless rather than more stable (you can see an image of the weed-like growth of US regulations here. It is no different in Europe).

This mountain of additional rules breeds complacency and new risks will eventually emerge at points that haven’t been considered yet. The above-mentioned “Houdini-like disappearance of market makers” is in fact a point that evidently hasn’t been properly thought through.

The regulatory spider-web, via JP Morgan. If we had a sound, free market-based monetary system, none of this would be required.

Conclusion

High yield debt is already looking a bit frayed around the edges, as the junk debtberg issued by the fracking industry and other energy companies over recent years suddenly meets with disapproval from investors (many of whom are currently dialing “1-800-Get-Me-Out”). However, we believe few people are aware of the potential for systemic instability that could result from the poisonous combination of mutual funds loaded to the gills with corporate debt and banks having removed themselves from market making activities. As long as monetary pumping by the Fed was still accelerating, or at least was still very sizable, it was easy to maintain the illusion that liquidity was practically infinite and vast numbers of greater fools were always queued up to pay even more outrageous prices so as to chase down a few additional basis points of yield. However, this happy facade may actually be about to crumble. Our bet is that by the time it does, regulators will still be “studying the issue”.