Courtesy of David Stockman via Contra Corner

If the BOJ’s mad money printers were treated as monetary pariahs by the rest of the world, it would at least imply that a modicum of sanity remains on the planet. But just the opposite is the case. Establishment institutions like the IMF, the US treasury and the other major central banks urge them on, while the Keynesian arson squad led by Professor Krugman actually faults Japan for being too tepid with its “stimulus”.

Now comes several new data points that absolutely confirm Japan is a financial mad house—-even as its policy model is embraced by mainstream officials and analysts peering from a distance. Front and center is the newly reported fact from the Cabinet Office that Japan’s household savings rate plunged to minus 1.3% in the most recent fiscal year, thereby entering negative territory for the first time since records were started in 1955.

Indeed, Japan had been heralded as a nation of savers only a generation ago. During the era before it’s plunge into bubble finance in the late 1980s, households routinely saved 15-25% of income. But after nearly three decades of Keynesian policies, Japan has now stumbled into an insuperable demographic/financial trap; and one that is unusually transparent and rigidly delineated, to boot.

Since Japan famously and doggedly refuses to accept immigrants, its long-term demographics are rigidly baked into the cake. Accordingly, anyone who will make a difference over the next several decades has already been born, counted, factored and attrited into the projections.

Japan’s work force of 80 million will thus drop to 40 million by 2060. At the same time, its current 30 million retires will continue to rise, meaning that its retiree rolls will ultimately exceed the number of workers.

Given those daunting facts, it follows that on the eve of its demographic bust Japan needs high savings and generous interest rates to augment retirement nest eggs; a strong exchange rate to attract foreign capital to help absorb its staggering $12 trillion of public debt, which already stands at a world leading 230% of GDP; and rising real incomes in order to shoulder the heavy taxation that is unavoidably necessary to close its fiscal gap and contain its mushrooming public debt.

With its debilitating Keynesian fiscal and monetary policies now re-upped on steroids under Abenomics, however, it goes without saying that nearly the opposite conditions prevail. Most notably, no household or institution anywhere in Japan can earn anything on liquid savings. The money market rate which determines deposit money yields was driven from a “high” of 100 basis points (as ridiculous as that sounds) at the time of the financial crisis to 10 basis points today, which is to say, nothing.

But what is even more astounding is that the yield on the 10-year JGB dipped to an all-time low of 0.31% in recent trading. Given the militant insistence of the BOJ that it will hit its 2% inflation target come hell or high water, it is accurate to say that the official policy of Abenomics is to cause holders of the government’s long-term debt to loose their shirts.

In fact, however, failing to think more than one step ahead, the BOJ actually wants banks, households and other financial institutions to sell their shirts at a handsome profit. That is to say, the BOJ’s bond purchase program is now so massive that it is buying 100% of the government’s gross debt issuance. In practical terms this means the float of public debt is actually being shrunk, and that the government bond market for all practical purposes has been extinguished by the BOJ.

There is nothing left except one relentless bid by the central bank. Recent data from Japan’s government pension insurance fund (GPIF), for example, show that the GPIF alone has already sold several hundred billions dollars worth of government bonds to the BOJ.

Needless to say, this radical monetization of the entire government bond market is an act of financial suicide. The BOJ now dares not stop the printing presses because absent the central bank’s big fat bid, the market would gap up violently. Yet 40% of Japan’s government revenue is already absorbed by servicing its gargantuan public debt. Even a 180 basis point increase in average yields (meaning that the 10-year JGB would still be under 2%) would absorb the remainder. That’s right, 100% of government revenue would be pre-empted by debt service.

This obviously amounts to a fiscal Looney Tunes scenario, but it is nonetheless embedded in the math. Even after the consumption tax increase from 5% to 8%, Japan’s general government is spending about 100 trillion yen per year while obtaining only 50 trillion yen in tax revenue.

As is evident in the chart above, this yawning gap has been building since the early 1990s when Keynesian missionaries converted the local fiscal apparatchiks to the religion of deficit finance. Now, having wasted 25 years figuratively building highways and bridges to nowhere, the Abe government has obtained a mandate not to raise taxes further until at least 2017. This means that the public debt will continue to soar, and that the BOJ will be under unrelenting pressure to monetize 100% of the new debt issues, least it risk a devastating flare-up in yields.

That makes for a juxtaposition that is out of this world. Since the early 1990’s Japanese bond yields have been falling owing to the BOJ’s financial repression, supplemented by the disinflationary boom stimulated on a worldwide basis by central bank fueled credit expansion. For all practical purposes, Japan’s government debt yields are at the zero bound, and, in fact, maturities up to two years are trading at negative yields.

By the same token, the public debt burden has been climbing relentlessly since the early 1980s owing to the embrace of Keynesian fiscal policies, as so vividly demonstrated in the graph below. And now owing to Abenomics, another 7-10% of GDP will be added annually to the public debt in the years just ahead.

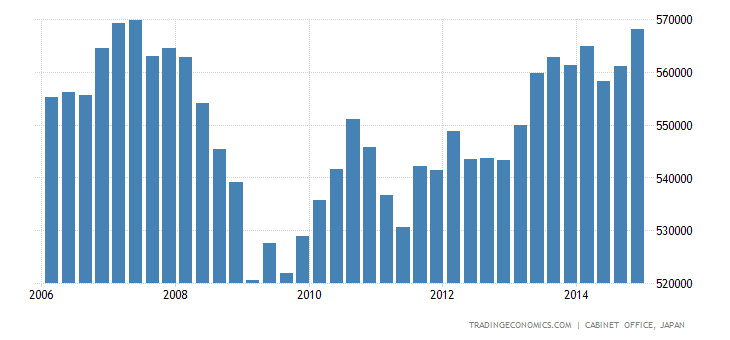

The desperate nature of Japan’s debt trap could not be more vividly depicted than in the chart below. In yen terms—-and that’s the metric that drives Japan’s budget receipts—–national income has not experienced any net growth since 2006! And Abenomics has not altered the picture in the slightest. During the most recent quarter nominal yen GNP was no higher than in January 2013.

In short, Japan’s fiscal equation is caught a brutal vise in which the denominator (GNP) is stranded on the flat line, while the numerator (public debt outstanding) continues to soar. So for the moment at least, Japan has resorted to 100% printing press finance of its public accounts.

But here’s the thing. The BOJ is destroying the yen and absolutely foreclosing the option of international capital inflows in the years ahead—save for short-term speculations by carry-traders in New York, London and the lesser gambling arenas around the globe. Consequently, the sharp fall of the exchange rate since 2012 is at risk for an accelerating plunge the longer the BOJ prints massive amounts of new yen to finance 100% of the government’s deficit.

Currency collapse, in turn, means that the cost-of-living on an economic archipelago that imports 100% of its energy and most of its raw materials is bound to rise, causing real wages to fall. In fact, that marks another fraught in-coming data point. In November, real cash wages plunged by 4.3% on a year/year basis, marking the 17th straight monthly decline and the steepest slide since December 2009.

<img alt="japanrealwaf" size-full="" wp-image-39061"="" data-cke-saved-src="https://confoundedinterest.files.wordpress.com/2014/12/japanrealwaf.png?w=1257&h=900" src="https://confoundedinterest.files.wordpress.com/2014/12/japanrealwaf.png?w=1257&h=900" style="width: 555px; height: 397px;">

Thus, the Keynesian disaster is complete. Massive BOJ money printing to fund the deficit is eroding real wages, thereby mitigating against tax increases capable of closing the fiscal gap and reducing the financing burden. The mad men at the BOJ are also, and simultaneously, obliterating the domestic saver with ZIRP and warding off international investors with a plunging exchange rate. Consequently, there is no honest way to finance the public deficit, meaning that the printing presses will continue to run red hot.

That this policy amounts to a financial suicide mission is obvious enough. But what is truly scary is that Japan’s policy model has been greenlighted and adopted in one form or another by governments and their central banking branches all around the world.