Higher Highs and Lower Lows

Courtesy of Michael Batnick

Harry Hopkins, head of the Civil Works Administration once said, “People don’t eat in the long run – they eat every day.”

This perfectly describes why it’s so difficult to earn market returns. We might know, or think we know, that stocks are biased upwards, but the market does a good job of making you work for those long-term returns. The long-term is a series of short-terms, and that’s where life is lived.

With the recent volatility, it’s hard to believe that it’s only been fourteen sessions since stocks made an all-time high. We’re once again reminded of what it feels like to lose money. (Take it easy, I’m aware that the S&P 500 is only 6% off it’s all time-high.)

Stocks behave differently in a falling market than they do in a rising one, so if this was the top, I wanted to give you a sense of what we might have to look forward to.

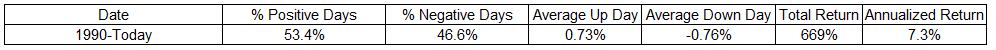

From 1990-today, the average return during days when the market rose was 0.73%. The average return for days when the market fell was -0.76%. Over that time period the market rising or falling during any given day was basically a coin flip, with stocks rising 53.4% of the time and falling 46.6% of the time. But over this 29 year period, there were 500 more up days than down days, which was enough to produce a 669% gain for the index (without dividends).

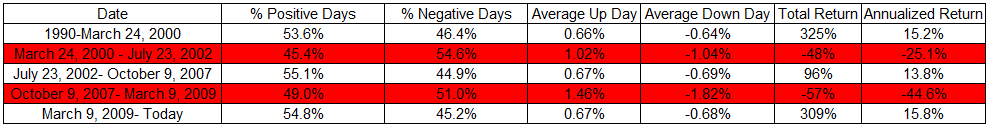

Like I said, stocks behave differently in different environments, and the table below breaks the period from 1990 to today into five distinct periods – three bull runs and [two] bear markets.

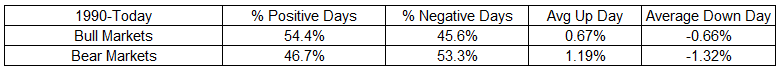

Below is the same table broken into bull and bear markets, using the same dates from above. In bull markets, the average up day is one basis point better than down days, but the fact that there are more up days than down days, even if the spread isn’t huge, makes all the difference in the world. The opposite is true in bear markets.

In bear markets, we see more negative days than positive days, and the average daily returns are roughly twice as large for up and down days.

My friend Jon Boorman recently said:

I know it’s pretty much guaranteed the market will rally without me, whenever that may be. That’s OK. It’s the price I pay for being protected from further downside until new trends emerge that meet my criteria. It’s not for everyone. It works for me.

The brilliant John Maynard Keynes said pretty much the exact opposite:

I do not feel that selling at very low prices is a remedy for having failed to sell at high ones…I feel no shame at being found owning a share when the bottom comes. I do not think it is the business, far less the duty, of an institutional investor or any other serious investor to be constantly considering whether he should cut and run on a failing market.

Many investors have convinced themselves, after nine years of gains, that like Keynes, they can buy and hold. But some things are just facts of life, and one of these facts is that bear markets happen and they happen because stocks are being sold.

As Boorman and Keynes have shown, there is no right way to invest. What’s right is whatever works for you. The worst thing an investor can find out during a bear market is that their strategy doesn’t suit their personality. Find what’s right for you then do your best to stay disciplined, for better and for worse.