Coronavirus market chaos: if central bankers fail to shore up confidence, then what?

EPA/Justin Lane

Courtesy of Ian Crowther, Sheffield Hallam University

Until recently, investors were enjoying substantial gains from a strong bull market in securities that essentially began in the depths of the financial crisis of 2007-09. With world markets now in serious turmoil, COVID-19 has probably brought this trend to an end. This atypical leftfield event has put its vicelike grip around the windpipes of stock market bourses and commodity markets across the world, and shows no signs of letting go.

Market confidence is weak and asset prices are very unstable – witness the latest rebounds on Tuesday March 10 after sharp declines the day before. Many stock markets are down by around 20% from January peaks, while oil has been destabilised by the price war between the Saudis and Russians.

Dow Jones Industrial Average

Google Finance

WTI Crude Oil

As quarantine and isolation measures pick up momentum in various critical markets, there is an air of panic about what lies ahead. Perhaps more importantly, how are the Masters of the Universe, aka the central bankers, going to react to this situation and breathe life back into asset prices?

Central banks responded to the 2007-09 financial crisis by sharply reducing interest rates and unleashing quantitative easing (QE) – essentially creating trillions of dollars to buy government bonds and other assets to prop up markets. This enabled the banks to recover and create additional cheap credit to propel the economy forward from deep recession.

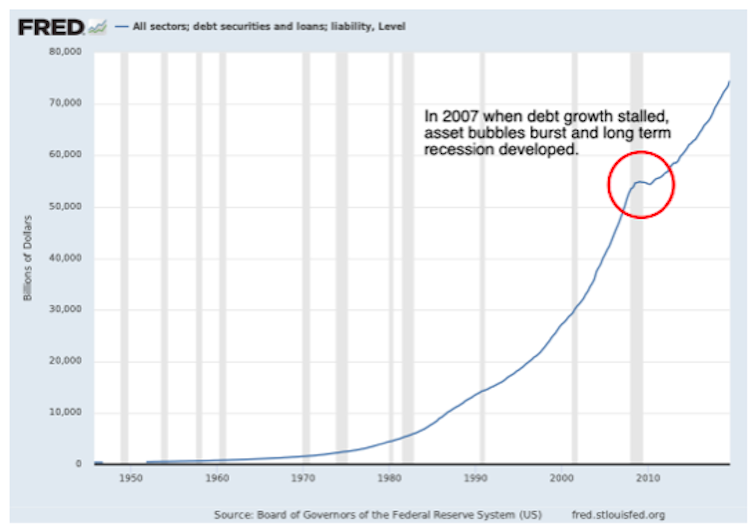

The line in the chart below shows the growth of all US debt over decades, which is a decent proxy for the world as a whole. You can see that growth soon resumed once the central bank policy response to the last economic crisis was in place. There is a direct correlation between the growth of firms, increasing GDP and ever-increasing debt creation via banks. In other words, when the debt tap switches off, the economy goes into a deep stall.

The 2007-09 central bank recovery strategy is problematic in two ways. In creating cheap debt, investors’ money and borrowings flow towards markets and asset classes that develop bubbles. Asset bubbles are a product of excessive demand and rising debt, where the prices of equities, bonds, property and so on exceed the underlying trading performance of the businesses to which they relate.

Government and central-bank balance sheets have also still not recovered from all the monetary largesse post-2007 – indeed, QE has broadly continued to the present day. It is therefore questionable whether there is enough firepower to continue propping up a market that is in dire need of a correction that should have happened after the 2007 crisis.

The new response

To halt the declines in demand that are causing firms to collapse, particularly in sectors like transport and tourism, the US Federal Reserve made an an emergency interest rate cut of 0.5 percentage points on Tuesday March 3. The Bank of England is likely to follow, with additional support from HM Treasury when Chancellor Rishi Sunak unveils his Budget. Predictions are also rife that there will be more emergency measures from the Fed soon.

From the market reaction to last week’s cut, there is little evidence of these moves working so far. And with interest rates already close to the lowest level possible – known as the zero-lower bound – there is limited room for manoeuvre.

The big issue is what happens if the virus persists into UK and US markets and default rates on the debt increase. Governments will potentially not only be dealing with a virus affecting public health but another contagion effect in financial debt markets in which investors start panicking about whether debts will be repaid and start demanding repayments.

Banks will take the hit. They are better prepared now to deal with credit losses because they have to hold more capital under the Basel III banking regulations and have invested heavily in so-called Coco Bonds that will help protect their balance sheets during a crisis by converting debts to shareholdings once certain thresholds have been breached.

But if containment measures fail – as we are seeing in Italy just now – the banks may still end up in trouble. They may also stop lending again, in which case the asset bubbles would collapse and a long-term recession would become a certainty. Central banks and governments would have to step in with more assistance: as well as further interest rate cuts, they look likely to try more QE and potentially bailouts like in 2007-09 if necessary. But given the limited scope this time around, if the global economy stalls for the long term, these measures might still fail and central bankers could potentially lose control of the marketplace altogether. In such a situation, we would be in truly uncharted territory.

Shape of things to come. Fileopen Creation

Historically, virus or health-related scares are typically over within six to 12 months. Affected markets and associated asset prices see recovery within a year or so. But on this occasion, it may well be naive to be so optimistic. Financial markets have become dependent on a macroeconomic policy response from central banks that recirculates ever-increasing levels of debt while not allowing prices to ever correct themselves. As a result, today’s asset bubbles are far worse than in 2007.

If panic sets in, any correction is likely to be more serious than during the last financial crisis. The best hope is probably that news about the outbreak gets better and the economy somehow muddles through. To take a couple of steps away from the abyss would certainly be a welcome relief right now.

Ian Crowther, Senior Lecturer in Banking and Financial Markets, Sheffield Hallam University

![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.