Governors take charge of response to the coronavirus

Washington state Gov. Jay Inslee ordered all bars, restaurants, entertainment and recreation facilities to temporarily close to fight the spread of COVID-19. Getty/Erika Schultz-Pool

Raymond Scheppach, University of Virginia

Just after every gubernatorial election, but before inaugurations, the National Governors Association organizes a two-day “New Governors School.” Current governors serve as the faculty for newly elected governors, offering a crash course in taking on states’ highest office from those with first-hand experience.

It is not by chance that the first of about eight sessions focuses on “What do you do in a crisis?”

One of the very first recommendations to all new governors during this session is to make their first appointment the state’s emergency preparedness agency director – not the chief of staff or even the governor’s liaison to the legislature. Those can wait.

The nation’s governors know a crisis can happen the day after the inauguration and they need to be prepared. Today, the coronavirus pandemic is rocking the world as we know it — quickly, radically and dramatically. Because the virus’ impact and timeline vary by geography and population, this unprecedented period demands state and local government leadership – and the very kind of preparation given governors in their pre-inaugural training.

Governors are taking aggressive action in their states to limit the spread of the COVID-19 virus. Each governor is tailoring the response to the unique needs of their state.

So far they’re doing well, according to public opinion polls. When asked who was handling the coronavirus crisis best – local, state or federal governments, or Congress – respondents to an Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research poll released on April 1 gave the highest approval rating to states.

New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo has become a prominent face of the response to the coronavirus. Getty/Albin Lohr-Jones/Pacific Press/LightRocket

Broad powers

I was the executive director of the National Governors Association from 1983 to 2011. In working with more than 300 governors, some lessons emerged.

Many state laws and executive orders provide governors with very broad powers during an emergency. Those powers derive from a governor’s fundamental charge, embedded in most state constitutions, to faithfully execute the state’s laws.

From natural disasters like flooding, hurricanes, earthquakes and tornadoes to human-caused, mass shootings and bombings, citizens and business look to governors for response and recovery.

Some of the lessons include:

-

Pull together a small, trusted ad-hoc team with the critical expertise to help the governor make decisions. Assign roles that address both short- and long-term needs and start thinking about recovery. Governors are making decisions based on the best advice of the health care specialists within state government, and at universities, and in coordination with the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

-

Be present, early and often. In a pandemic, leaders can’t go to the site of the emergency the way they would during other catastrophes, but they can be seen in many other ways, providing information, surveying needs and helping to calm the public.

-

Vet and verify all information, using your crisis team before making it public. Public trust demands accurate information. Rumors will always circulate, but you can minimize their impact with a constant flow of accurate information.

-

Be clear about what is expected and give people specific ways to help. Even simple tips like washing hands and caring for elders give people something tangible to do when so many factors feel out of their control. Almost all states have closed schools and limited the size of gatherings, generally to 10 or fewer people. Many have also restricted state employee travel and implemented state restrictions on non-essential businesses. Some of the restrictions are mandatory while others are recommended or only affect certain activities like bars.

-

Transcend party and governmental lines. Most governors are searching for protective equipment for health care workers and ventilators for the surge in new cases. During many crises they work through the Emergency Management Assistance Compact, which is a compact ratified by Congress of which all states and some territories are members. Here they often share emergency medical services and even National Guard equipment and units.

It works well when one or two states are facing a crisis, but with COVID-19 all states are facing it, so they have to depend on the federal government. For many this will be a test of patience and not engaging in partisan tactics.

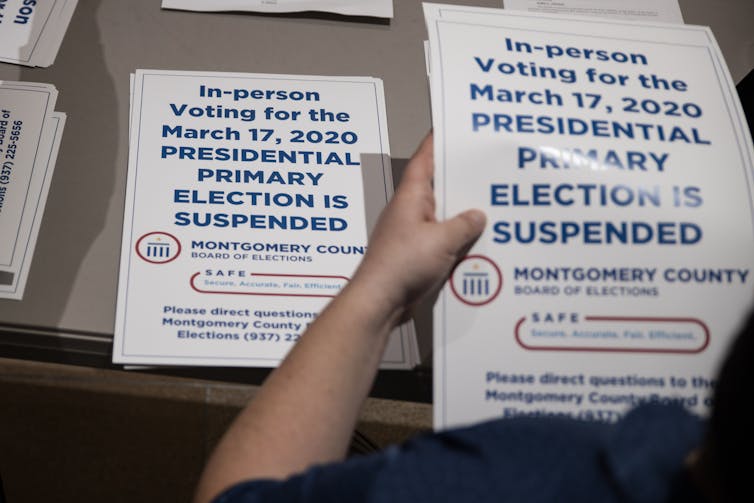

Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine, a Republican, had state health officials cancel his state’s Democratic primary in mid-March. Getty/Megan Jelinger/AFP

Plenty of practice

While President Donald Trump has waxed and waned in his affection for some of the nation’s governors during the crisis, he has respected the governors’ power to decide measures to protect from and respond to COVID-19. He recently indicated he was thinking of quarantining residents from New York, New Jersey and Connecticut, but then decided not to after governors objected.

For better or worse, the states’ highest offices get plenty of practice. Governors usually face at least one crisis during their term in office, and many will manage several. Things can go bad quickly: Consider Pennsylvania Gov. Dick Thornburgh, who had only been in office for 72 days when the 1979 Three Mile Island nuclear accident struck.

Governors believe they are responsible for the health and welfare of their citizens and they take it seriously and personally. That’s because governors generally know several thousand people across the state, from the largest city to the smallest towns.

This personal connection and the enormous responsibility of responding to a pandemic are creating the biggest challenge governors’ offices have faced in the history of the nation.

How they respond will have broad consequences for generations.

[You need to understand the coronavirus pandemic, and we can help. Read The Conversation’s newsletter.]

Raymond Scheppach, Professor of Public Policy, University of Virginia

![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.