Coronavirus, 'Plandemic' and the seven traits of conspiratorial thinking

No matter the details of the plot, conspiracy theories follow common patterns of thought. Ranta Images/iStock/Getty Images Plus

Courtesy of John Cook, George Mason University; Sander van der Linden, University of Cambridge; Stephan Lewandowsky, University of Bristol, and Ullrich Ecker, University of Western Australia

The conspiracy theory video “Plandemic” recently went viral. Despite being taken down by YouTube and Facebook, it continues to get uploaded and viewed millions of times. The video is an interview with conspiracy theorist Judy Mikovits, a disgraced former virology researcher who believes the COVID-19 pandemic is based on vast deception, with the purpose of profiting from selling vaccinations.

The video is rife with misinformation and conspiracy theories. Many high-quality fact-checks and debunkings have been published by reputable outlets such as Science, Politifact and FactCheck.

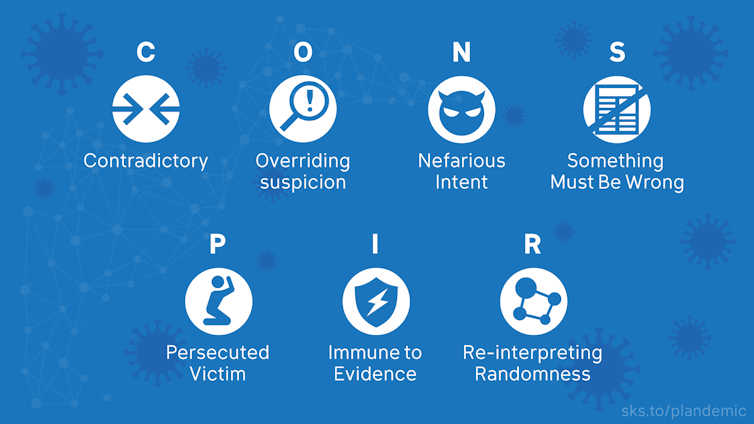

As scholars who research how to counter science misinformation and conspiracy theories, we believe there is also value in exposing the rhetorical techniques used in “Plandemic.” As we outline in our Conspiracy Theory Handbook and How to Spot COVID-19 Conspiracy Theories, there are seven distinctive traits of conspiratorial thinking. “Plandemic” offers textbook examples of them all.

Learning these traits can help you spot the red flags of a baseless conspiracy theory and hopefully build up some resistance to being taken in by this kind of thinking. This is an important skill given the current surge of pandemic-fueled conspiracy theories.

The seven traits of conspiratorial thinking. John Cook, CC BY-ND

1. Contradictory beliefs

Conspiracy theorists are so committed to disbelieving an official account, it doesn’t matter if their belief system is internally contradictory. The “Plandemic” video advances two false origin stories for the coronavirus. It argues that SARS-CoV-2 came from a lab in Wuhan – but also argues that everybody already has the coronavirus from previous vaccinations, and wearing masks activates it. Believing both causes is mutually inconsistent.

2. Overriding suspicion

Conspiracy theorists are overwhelmingly suspicious toward the official account. That means any scientific evidence that doesn’t fit into the conspiracy theory must be faked.

But if you think the scientific data is faked, that leads down the rabbit hole of believing that any scientific organization publishing or endorsing research consistent with the “official account” must be in on the conspiracy. For COVID-19, this includes the World Health Organization, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Food and Drug Administration, Anthony Fauci… basically, any group or person who actually knows anything about science must be part of the conspiracy.

3. Nefarious intent

In a conspiracy theory, the conspirators are assumed to have evil motives. In the case of “Plandemic,” there’s no limit to the nefarious intent. The video suggests scientists including Anthony Fauci engineered the COVID-19 pandemic, a plot which involves killing hundreds of thousands of people so far for potentially billions of dollars of profit.

Conspiratorial thinking finds evil intentions at all levels of the presumed conspiracy. MANDEL NGAN/AFP via Getty Images

4. Conviction something’s wrong

Conspiracy theorists may occasionally abandon specific ideas when they become untenable. But those revisions tend not to change their overall conclusion that “something must be wrong” and that the official account is based on deception.

When “Plandemic” filmmaker Mikki Willis was asked if he really believed COVID-19 was intentionally started for profit, his response was “I don’t know, to be clear, if it’s an intentional or naturally occurring situation. I have no idea.”

He has no idea. All he knows for sure is something must be wrong: “It’s too fishy.”

5. Persecuted victim

Conspiracy theorists think of themselves as the victims of organized persecution. “Plandemic” further ratchets up the persecuted victimhood by characterizing the entire world population as victims of a vast deception, which is disseminated by the media and even ourselves as unwitting accomplices.

At the same time, conspiracy theorists see themselves as brave heroes taking on the villainous conspirators.

6. Immunity to evidence

It’s so hard to change a conspiracy theorist’s mind because their theories are self-sealing. Even absence of evidence for a theory becomes evidence for the theory: The reason there’s no proof of the conspiracy is because the conspirators did such a good job covering it up.

7. Reinterpreting randomness

Conspiracy theorists see patterns everywhere – they’re all about connecting the dots. Random events are reinterpreted as being caused by the conspiracy and woven into a broader, interconnected pattern. Any connections are imbued with sinister meaning.

For example, the “Plandemic” video suggestively points to the U.S. National Institutes of Health funding that has gone to the Wuhan Institute of Virology in China. This is despite the fact that the lab is just one of many international collaborators on a project that sought to examine the risk of future viruses emerging from wildlife.

Learning about common traits of conspiratorial thinking can help you recognize and resist conspiracy theories.

Critical thinking is the antidote

As we explore in our Conspiracy Theory Handbook, there are a variety of strategies you can use in response to conspiracy theories.

One approach is to inoculate yourself and your social networks by identifying and calling out the traits of conspiratorial thinking. Another approach is to “cognitively empower” people, by encouraging them to think analytically. The antidote to conspiratorial thinking is critical thinking, which involves healthy skepticism of official accounts while carefully considering available evidence.

Understanding and revealing the techniques of conspiracy theorists is key to inoculating yourself and others from being misled, especially when we are most vulnerable: in times of crises and uncertainty.

[Get facts about coronavirus and the latest research. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]

John Cook, Research Assistant Professor, Center for Climate Change Communication, George Mason University; Sander van der Linden, Director, Cambridge Social Decision-Making Lab, University of Cambridge; Stephan Lewandowsky, Chair of Cognitive Psychology, University of Bristol, and Ullrich Ecker, Associate Professor of Cognitive Science, University of Western Australia

![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.