Federal leaders have two options if they want to rein in Trump

President Donald Trump gestures during a Jan. 6 speech in Washington, D.C. AP Photo/Jacquelyn Martin

Courtesy of Kirsten Carlson, Wayne State University

As the world reacts to the Jan. 6 armed attack on the U.S. Capitol encouraged by President Donald Trump, many Americans are wondering what happens next. Members of Congress, high-level officials and even major corporations and business groups have called for Trump’s removal from office.

Prominent elected and appointed officials appear to have already sidelined Trump informally. Vice President Mike Pence was reportedly the highest-level official to review the decision to call out the D.C. National Guard to respond to the assault on the Capitol.

Informal actions like this may continue, including House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s reported request that Gen. Mark Milley, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, restrict Trump’s ability to use the nuclear codes. But political leaders are considering more formal options as well. They have two ways to handle it: impeachment and the 25th Amendment.

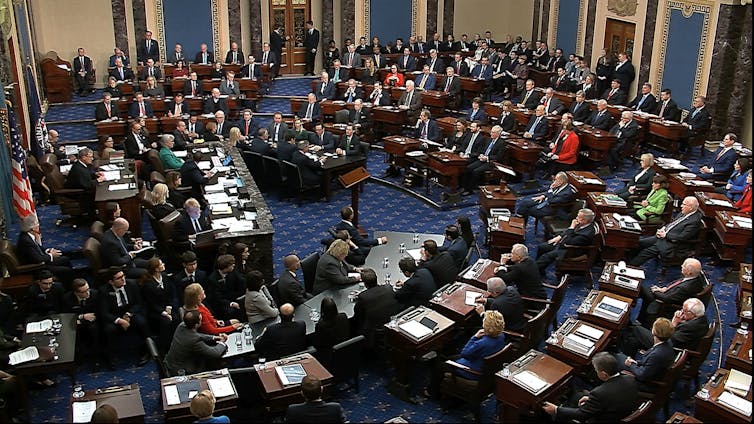

Donald Trump has already been impeached once, but was not convicted. Senate Television via AP

Impeachment

Article II of the U.S. Constitution authorizes Congress to impeach and remove the president – and other federal officials – from office for “Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors.” The founders included this provision as a tool to punish a president for misconduct and abuses of power. It’s one of the many ways that Congress keeps the executive branch in check.

Impeachment proceedings begin in the House of Representatives. A member of the House files a resolution for impeachment. The resolution goes to the House Judiciary Committee, which usually holds a hearing to evaluate the resolution. If the House Judiciary Committee thinks impeachment is proper, its members draft and vote on articles of impeachment. Once the House Judiciary Committee approves articles of impeachment, they go to the full House for a vote.

If the House of Representatives impeaches a president or another official, the action then moves to the Senate. Under the Constitution’s Article I, the Senate has the responsibility for determining whether to remove the person from office. Normally, the Senate holds a trial, but it controls its procedures and can limit the process if it wants.

Ultimately, the Senate votes on whether to remove the president – which requires a two-thirds majority, or 67 senators. To date, the Senate has never voted to remove a president from office, although it almost did in 1868, when President Andrew Johnson escaped removal from office by one vote.

The Senate also has the power to disqualify a public official from holding public office in the future. If the person is convicted and removed from office, only then can senators vote on whether to permanently disqualify that person from ever again holding federal office. Members of Congress proposing the impeachment of Trump have promised to include a provision to do so. A simple majority vote is all that’s required then.

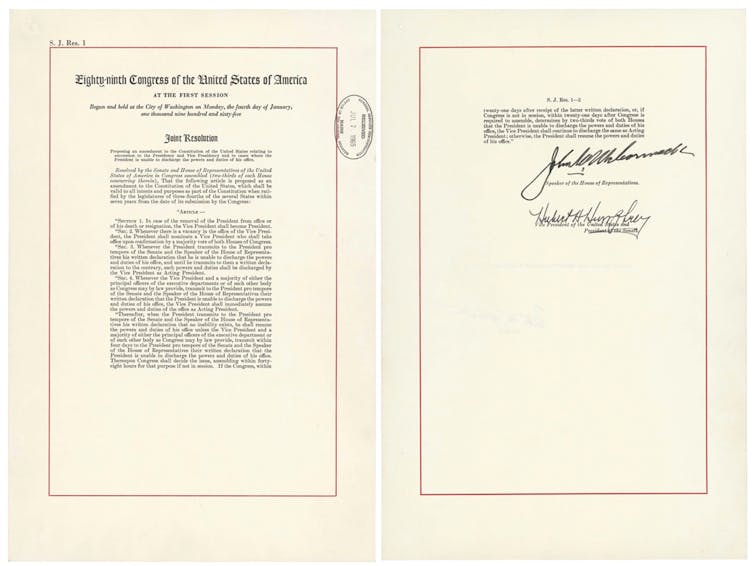

The 25th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. National Archives via AP

25th Amendment

The Constitution’s 25th Amendment provides a second way for high-level officials to remove a president from office. It was ratified in 1967 in the wake of the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy – who was succeeded by Lyndon Johnson, who had already had one heart attack – as well as delayed disclosure of health problems experienced by Kennedy’s predecessor, Dwight Eisenhower.

The 25th Amendment provides detailed procedures on what happens if a president resigns, dies in office, has a temporary disability or is no longer fit for office.

It has never been invoked against a president’s will, and has been used only to temporarily transfer power, such as when a president is undergoing a medical procedure requiring anesthesia.

Section 4 of the 25th Amendment authorizes high-level officials – either the vice president and a majority of the Cabinet or another body designated by Congress – to remove a president from office without his consent when he is “unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office.” Congress has yet to designate an alternative body, and scholars disagree over the role, if any, of acting Cabinet officials.

The high-level officials simply send a written declaration to the president pro tempore of the Senate – the longest-serving senator from the majority party – and the speaker of the House of Representatives, stating that the president is unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office. The vice president immediately assumes the powers and duties of the president.

The president, however, can fight back. He or she can seek to resume their powers by informing congressional leadership in writing that they are fit for office and no disability exists. But the president doesn’t get the presidency back just by saying this.

The high-level officials originally questioning the president’s fitness then have four days to decide whether they disagree with the president. If they notify congressional leadership that they disagree, the vice president retains control and Congress has 48 hours to convene to discuss the issue. Congress has 21 days to debate and vote on whether the president is unfit or unable to resume his powers.

The vice president remains the acting president until Congress votes or the 21-day period lapses. A two-thirds majority vote by members of both houses of Congress is required to remove the president from office. If that vote fails or does not happen within the 21-day period, the president resumes his powers immediately.

It is possible that Trump will remain in office through the end of his term on Jan. 20. But once he leaves office, he will no longer have the presidential immunity that has at least partially shielded him from many criminal and civil inquiries about his time in office and before.

Editor’s note: This article was updated on Jan. 9, 2021, to include additional informal measures taken to limit Trump’s power.

[Get our most insightful politics and election stories. Sign up for The Conversation’s Politics Weekly.]![]()

Kirsten Carlson, Associate Professor of Law and Adjunct Associate Professor of Political Science, Wayne State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.