An infectious disease expert explains new federal rules on ‘mix-and-match’ vaccine booster shots

Discuss with your doctor whether or not you need a booster – and if so, which vaccine will work best for you. Justin Sullivan/Getty Images News via Getty Images

Courtesy of Glenn J. Rapsinski, University of Pittsburgh Health Sciences

Many Americans now have the green light to get a COVID-19 vaccine booster – and the flexibility to receive a different brand than the original vaccine they received.

On the heels of the Food and Drug Administration’s Sept. 22, 2021, emergency use authorization of a third dose – or “booster shot” – of the Pfizer/BioNtech vaccine for certain Americans, on Oct. 20, the agency also gave emergency authorization to a third Moderna shot and a second dose of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine.

On Oct. 21, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention also recommended these vaccinations in light of the FDA’s authorization. The CDC’s signoff will make the Moderna booster shot available to people 65 and older, younger adults at higher risk of severe COVID-19 due to medical conditions and those who are at increased risk due to their workplace environment. People are now eligible for the Moderna booster six months after completion of their original series – as is already the case for the third Pfizer shot. The authorization made all Johnson & Johnson vaccine recipients eligible for a second shot two months after the initial dose.

Notably, the FDA and CDC also authorized a “mix-and-match” strategy, enabling eligible Americans to get a booster shot from a brand different from their original vaccine.

As an infectious disease expert, I have closely followed the development of the COVID-19 vaccines and the research on how immunity and vaccine efficacy shift over time.

With the swirling mass of news around how effective the COVID-19 vaccines are and who needs booster shots and when, it can be challenging and confusing to make sense of it all. But understanding how the immune system works can help bring clarity to the reasons some people could benefit from the authorized shots.

How vaccine efficacy evolves

The discussion and perceived urgency around booster shots has partially been driven by the occurrence of “breakthrough” COVID-19 infections in fully vaccinated people. The term breakthrough misleadingly implies that the vaccines failed, but this is not the case. The intention of the vaccine is to reduce hospitalizations and deaths, a goal that the COVID-19 vaccines continue to meet.

While the Pfizer/Biontech mRNA vaccine shows decreasing efficacy against asymptomatic and mild infections over the first six months after vaccination, studies show that it continues to be highly effective at preventing hospitalizations and deaths, including against the delta variant, in the first six months.

A clinical study of the Moderna vaccine showed that antibody levels remain strong after six months as well. But studies after the six-month mark have been mixed, with reports of waning antibody levels leaving some researchers concerned that a booster shot strategy is essential. However, the limited data left too many questions for the FDA and CDC to approve a booster shot for all Americans, at least at this time.

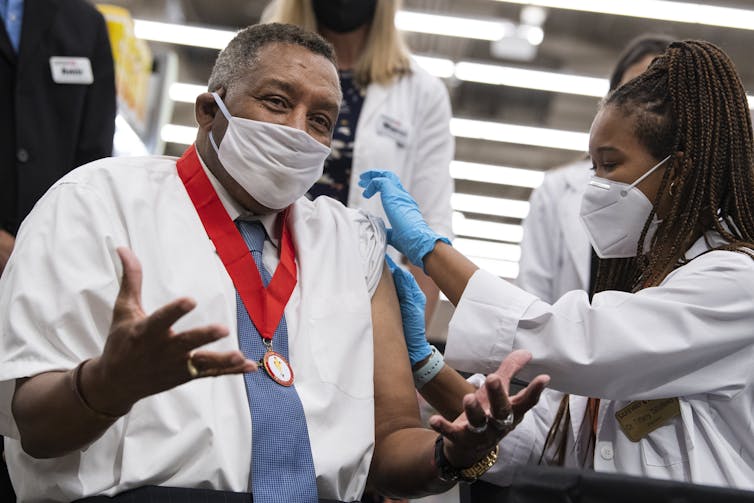

Frank Mallone, 71, receives a Pfizer COVID-19 vaccine booster shot in Washington, D.C. Tom Williams/CQ-Roll Call, Inc. via Getty Images

Still, the overwhelming majority of intensive care admissions and deaths from COVID-19 continue to be in unvaccinated people. The rare deaths from COVID-19 in vaccinated people are mostly in people with immune systems weakened either by age or underlying conditions, which is why booster shots have been authorized for these groups. While boosters clearly help the individual, it is just as important for everyone to get fully vaccinated to protect vulnerable people by reducing the overall number of cases in the community.

Vaccines rev up the immune system

All three of the authorized vaccines in the U.S. work by giving the body instructions for making the spike protein from the SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes COVID-19. The spike protein, which resembles a stem with three buds on the end, is what enables the actual virus to invade cells and cause infection. The mRNA vaccines by Pfizer/BioNtech and Moderna provide the blueprint for the spike protein in the form of mRNA in a drug-delivery system called a lipid nanoparticle. The Johnson & Johnson vaccine gives DNA instructions inside the coat of a different virus, called a viral vector.

The immune system quickly recognizes that these foreign proteins do not belong, and it generates an immune response to fight them off. These newfound defenses gear the body up to protect against the real virus. During this primary immune response, immune cells encounter spike proteins and, as a defense, they produce antibodies, “memory” cells and T-cells that can kill infected cells to prevent the virus from multiplying. Some of these antibodies and T-cells from the primary immune response persist over time, though they decrease during the first month after vaccination, while memory cells last much longer.

Then, when someone gets an additional dose of vaccine, the immune system goes through a secondary immune response. Thanks to the memory cells, the secondary immune response activates more rapidly, triggering lots of antibody production and T-cell activation. More mature antibodies are produced as well, and they are even better at trapping the spike proteins. And T-cells proliferate, helping to stop the intruder in its tracks. This type of secondary immune response can be activated again and again when repeat exposures to a vaccine – or booster doses – occur. Each time, the immune response mounts a stronger and more effective defense.

Mix-and-match vaccine boosters

Multiple studies, including preliminary research from the National Institutes of Health that is not yet peer-reviewed, have shown that the mix-and-match strategy is safe and effective at providing a significant immune boost.

Additionally, mixing vaccine types may be most beneficial in those who initially received a non-mRNA vaccine. The NIH data suggests that people who got the single-shot Johnson & Johnson vaccine had a bigger increase and achieved a higher antibody concentration after receiving an mRNA booster than if they received the Johnson & Johnson booster. For people who first received one of the mRNA vaccines, Pfizer or Moderna, followed by a third shot with Johnson & Johnson, the antibody response was similar to that seen in those who got a third, or homologous, mRNA dose.

Studies exploring why the mix-and-match strategy is more effective with some initial vaccines and not others are underway. Understanding this and the effectiveness of different vaccine combinations, including using vaccines that are authorized in other countries, will help improve vaccination strategies all over the world.

Interchanging vaccine types may have greater advantages in some people than in others, which will become clearer as more data is gathered. But the good news is that the immune response seems to get a solid boost from booster shots, regardless of which vaccine combination is used.

[Get The Conversation’s most important coronavirus headlines, weekly in a science newsletter]![]()

Glenn J. Rapsinski, Pediatric Infectious Diseases Fellow, University of Pittsburgh Health Sciences

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.