5 drugs that changed the world (and what went wrong)

By Philippa Martyr, The University of Western Australia

It’s hard to measure the impact of any one drug on world history. But here are five drugs we can safely say made a huge difference to our lives, often in ways we didn’t expect.

They have brought some incredible benefits. But they’ve usually also come with a legacy of complications we need to look at critically.

It’s a good reminder that today’s wonder drug may be tomorrow’s problem drug.

1. Anaesthesia

In the late 1700s, English chemist Joseph Priestley made a gas he called “phlogisticated nitrous air” (nitrous oxide). English chemist Humphry Davy thought it could be used as pain relief in surgery, but instead it became a recreational drug.

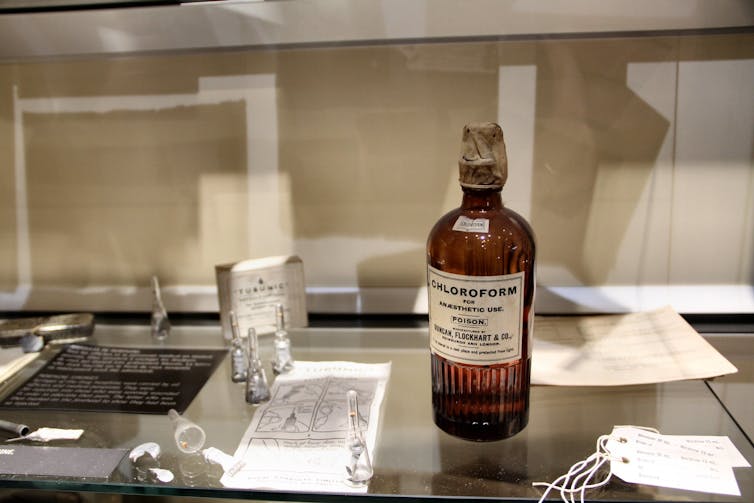

It wasn’t until 1834 that we reached another milestone. That’s when French chemist Jean-Baptiste Dumas named a new gas chloroform. Scottish doctor James Young Simpson used it in 1847 to assist a birth.

Soon anaesthesia was more widely used during surgery, bringing better recovery rates. Before anaesthesia, surgical patients would often die of shock from the pain.

But any drug that can make people unconscious can also cause harm. Modern anaesthetics are still dangerous because of the risks of suppressing the nervous system.

2. Penicillin

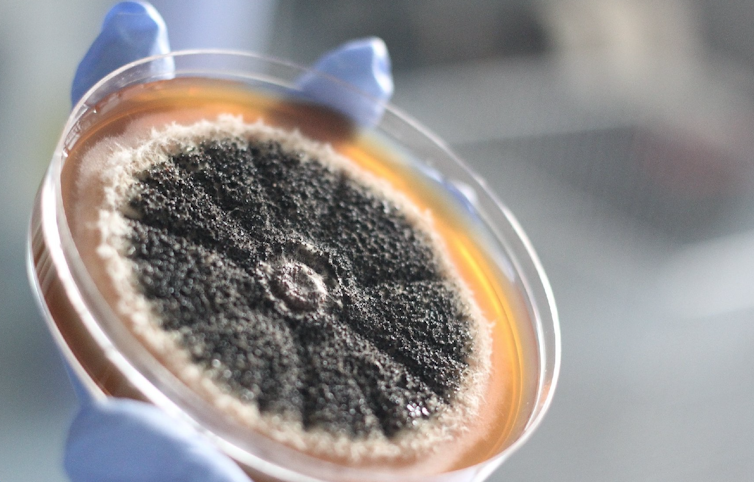

What happened in 1928 to Scottish physician Alexander Fleming is one of the classic stories of accidental drug discovery.

Fleming went on holiday, leaving some cultures of the bacterium streptococcus on his laboratory bench. When he came back, he saw some airborne penicillium (a fungal contaminant) had stopped the streptococcus from growing.

Australian pathologist Howard Florey and his team stabilised penicillin and carried out the first human experiments. With American financing, penicillin was mass-produced and changed the course of World War II. It was used to treat thousands of service personnel.

Penicillin and its descendants are enormously successful front-line drugs for conditions that once killed millions of people. However, their widespread use has led to drug-resistant strains of bacteria.

3. Nitroglycerin

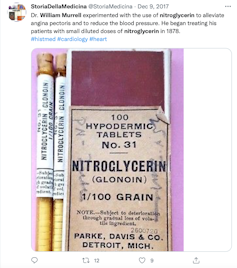

Nitroglycerin was invented in 1847 and displaced gunpowder as the most powerful explosive in the world. It was also the first modern drug to treat angina, the chest pain associated with heart disease.

Factory workers exposed to the explosive began to experience headaches and flushing in the face. This was because nitroglycerin is a vasodilator – it dilates (opens) the blood vessels.

London physician William Murrell experimented with nitroglycerin on himself and tried it on his angina patients. They got almost immediate relief.

Nitroglycerin made it possible for millions of people with angina to live relatively normal lives. It also paved the way for medications such as blood pressure-lowering drugs, beta-blockers and statins. These medicines have extended lives and increased the average lifespan in Western countries.

But because people’s lives are now extended, there are now higher rates of deaths from cancer and other non-communicable diseases. So nitroglycerin turned out to be a world-changing drug in unexpected ways.

4. The pill

In 1951, US birth control advocate Margaret Sanger asked researcher Gregory Pincus to develop an effective hormonal contraceptive, funded by heiress Katharine McCormick.

Pincus found that progesterone helped to stop ovulation, and used this to develop a trial pill. Clinical trials were conducted on vulnerable women, notably in Puerto Rico, where there were concerns about informed consent and side effects.

The new drug was released by GD Searle & Co as Enovid in 1960, with US Food and Drug Administration approval. This was granted because the risk of pregnancy was seen as greater than the risk of side effects, such as blood clots and strokes.

#OnThisDay in 1960, a birth-control pill, made by the G.D. Searle Company of Chicago was approved by the FDA. Before that, clinical trials ran in Puerto Rico, where poor women were given high doses of the drug without disclosure that it was in trial or of possible side effects. pic.twitter.com/jTPXdb8mOb

— Unsung History Podcast (@Unsung__History) May 10, 2022

It took ten years to prove a link between oral contraceptive use and serious side effects. After a 1970 US government inquiry, the pill’s hormone levels were lowered dramatically. Another outcome was the patient information sheet you will now find inside all prescription drug packets.

The pill caused major global demographic changes with smaller families and increased incomes as women re-entered the workforce. However, it’s still raising questions about how the medical profession has experimented on women’s bodies.

5. Diazepam

The first benzodiazepine, a type of nervous system depressant, was created in 1955 and marketed by drug company Hoffmann-La Roche as Librium.

This and related drugs were not sold as “cures” for anxiety. Instead, they were supposed to help people engage in psychotherapy, which was seen as the real solution.

Polish-American chemist Leo Sternbach and his research group chemically altered Librium in 1959, producing a much more powerful drug. This was diazepam, marketed from 1963 as Valium.

Cheap, easily available drugs like these had a huge impact. From 1969 until 1982, Valium was the top-selling pharmaceutical in the United States. These drugs created a culture of managing stress and anxiety with medication.

Valium paved the way for modern antidepressants. It was more difficult (but not impossible) to overdose on these newer drugs, and they had fewer side effects. The first SSRI, or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, was fluoxetine, marketed from 1987 as Prozac.![]()

Philippa Martyr, Lecturer, Pharmacology, Women’s Health, School of Biomedical Sciences, The University of Western Australia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.