If you thought this summer’s heat waves were bad, a new study has some disturbing news about dangerous heat in the future

By David Battisti, University of Washington

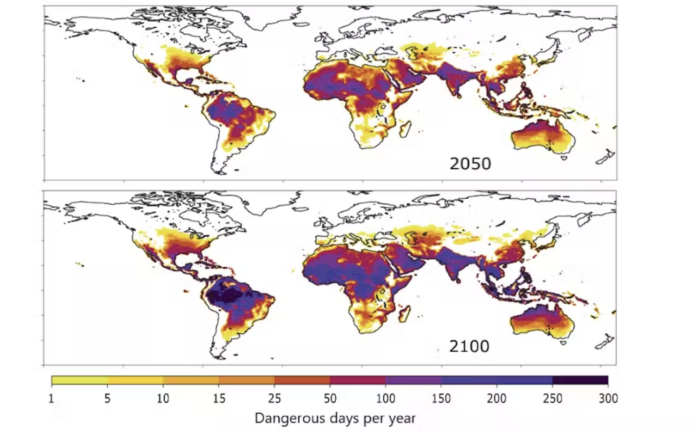

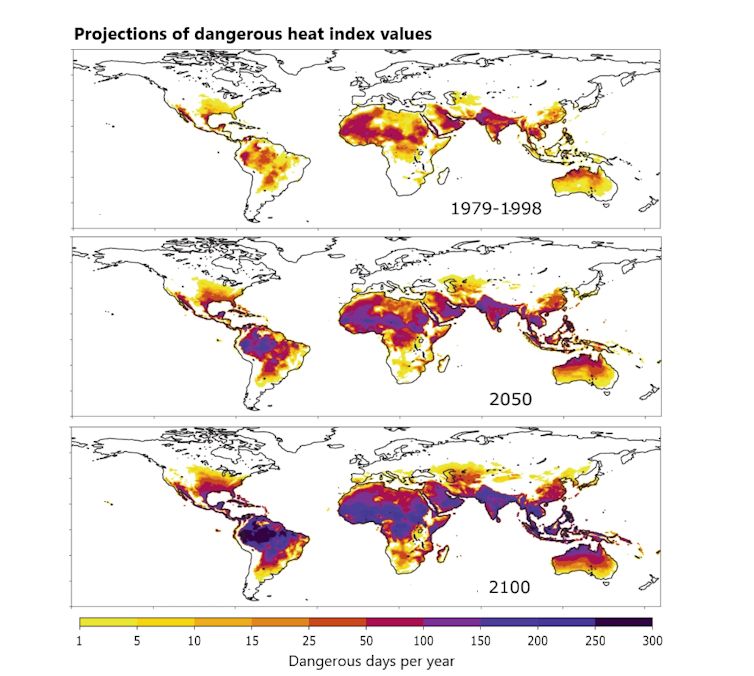

As global temperatures rise, people in the tropics, including places like India and Africa’s Sahel region, will likely face dangerously hot conditions almost daily by the end of the century, a new study shows.

The mid-latitudes, including the U.S., will also face increasing risks. There, the number of dangerously hot days, marked by temperatures and humidity high enough to cause heat exhaustion, is projected to double by the 2050s and continue to rise.

In the study, scientists looked at population growth, economic development patterns, energy choices and climate models to project how heat index levels – the combination of heat and humidity – will change over time. We asked University of Washington atmospheric scientist David Battisti, a co-author of the study, published Aug. 25, 2022, to explain the findings and what they mean for humans around the world.

What does the new study tell us about heat waves in the future, and importantly the impact on people?

There are two sources of uncertainty when it comes to future temperature. One is how much carbon dioxide humans are going to emit – that depends on things like population, energy choices and how much the economy grows. The other is how much warming those greenhouse gas emissions will cause.

In both, scientists have a really good sense of the likelihood of various scenarios. For this study, we combined those estimates to get a likelihood in the future of having dangerous and life-threatening temperatures.

We looked at what these “dangerously high” and “extremely dangerous” levels on the heat index would mean for daily life in both the tropics and in the mid-latitudes.

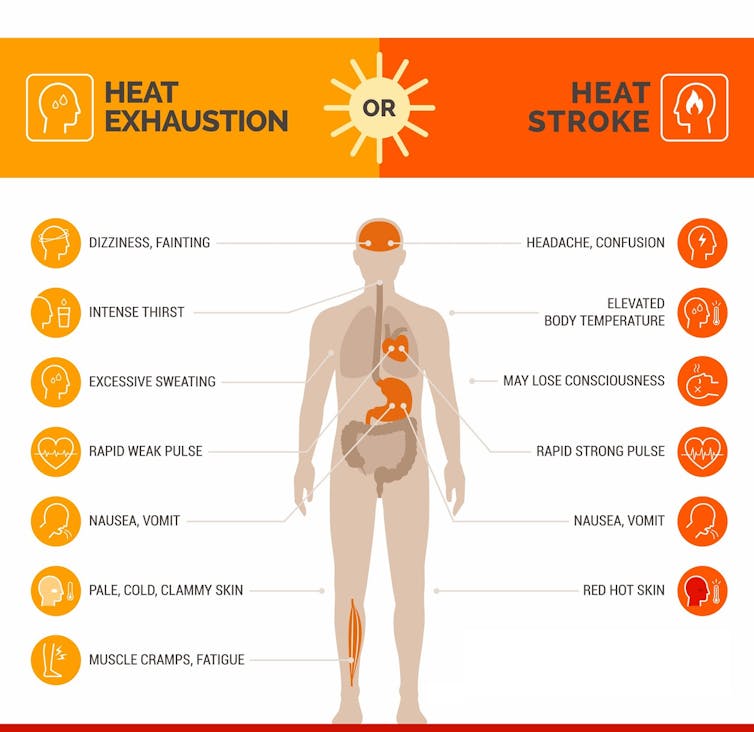

“Dangerous” in this case refers to the likelihood of heat exhaustion. Heat exhaustion won’t kill you if you’re able to stop and slow down – it’s characterized by fatigue, nausea, a slowed heartbeat, possibly fainting. But you really can’t work under these conditions.

The heat index indicates when a person is likely to reach that threshold. The National Weather Service defines “dangerous” as a heat index of 103 F (39.4 C), and “extremely dangerous” as 125 F (51.7 C). If a person gets to “extremely dangerous” temperatures, that can lead to heat stroke. At that level, you have a few hours to get medical attention to cool your body down, or you die.

“Extremely dangerous” heat index conditions are almost unheard of today. They happen in a few locations near the Gulf of Oman, for example, for maybe a few days in a decade.

But the odds of the number of “dangerous” days are increasing as the planet warms. We’ll likely have about the same weather variability as today, but it’s all happening on top of a higher average temperature. So, the likelihood of extremely hot conditions increases.

What does your study show for each region?

In the mid-latitudes by 2050, we’ll see the number of dangerous heat days double in the most likely future scenario – even under modest greenhouse gas emissions that would meet the Paris climate agreement target of keeping warming under 2 C (3.6 F).

In the Southeastern U.S., the most likely scenario is that people will experience a month or two of dangerous heat days every year. The same is likely in parts of China, where some regions have been sweating through a summer 2022 heat wave for over two straight months.

We found that by the end of the century, most places in the mid-latitudes will see a three- to tenfold increase in the number of dangerous days.

In the tropics, such as parts of India, the heat index right now can exceed the dangerous level for a few weeks a year. It’s been like that for the past 20 to 30 years. By 2050, those conditions are likely to occur over several months each year, we found. And by the end of the century, many places will see those conditions most of the year.

What that means in practice is if you’re a rich country like the U.S., most people can afford or find air conditioning. But if you’re in the tropics, where about half the world’s population lives and poverty is higher, the heat is a more serious problem for a good part of the year. And a large percentage of people there work outside in agriculture.

As we get toward the end of the century, we’ll start exceeding “extremely dangerous” conditions in several places, primarily in the tropics.

Northern India could see over a month per year in extremely dangerous conditions. Africa’s Sahel region, where poverty is widespread, could see a few weeks of extremely dangerous conditions per year.

Can humans adapt to what sounds like a dystopian future?

If you’re a rich country, you can build cooling facilities and generate electricity to run air conditioners – hopefully they won’t be powered with fossil fuels, which would further warm the planet.

If you’re a developing country, a very large fraction of people work outdoors in agriculture to earn money to buy food. There, if you think about it, there aren’t a lot of options.

Migrant workers in the U.S. also face more difficult conditions. A farm might be able to provide cooling facilities, but farmers’ margins are pretty small and migrant workers are often paid by volume, so when they aren’t picking, they aren’t paid.

Eventually, conditions will get to the point that more workers are overheating and dying.

The heat will be a problem for crops, too. We expect most of the major grains to be less productive in the future because of heat stress. In the mid-latitudes right now, we’re close to optimal temperatures for growing grains. But as temperatures increase, grain yield goes down. In the tropics, that could be anywhere between a 10% to 15% reduction per degree Celsius increase. That’s a pretty big hit.

What can be done to avoid these risks?

Part of our work in this study was determining the odds that the world will actually meet the Paris agreement. We found that to be around 0.1%. Basically, it’s not going to happen.

By the end of the century, we found the most likely scenario is that the planet will see 5.4 F (3 C) of warming globally compared to pre-industrial times. Land warms faster than ocean, so that translates to about a 7 F (3.9 C) increase for places where we live, work and play – and you can get a sense of the future.

The faster renewable energy comes online and fossil fuel use is shut down, the better the chances of avoiding that.![]()

David Battisti, Professor of Atmospheric Sciences, University of Washington

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.