Four ‘fronts’ in the Ukraine-Russia war to look out for as winter bites

By Scott Lucas, University College Dublin

Russia had expected to be victorious long before now. Its initial plan envisaged ground assaults across Ukraine in the first ten days and a rapid capitulation thereafter. But Kyiv did not fall – and Ukraine’s president, Volodymyr Zelensky, refused to leave the capital, saying, “I need ammunition, not a ride,” as he rallied Ukrainians. Russian troops had withdrawn from northern Ukraine by April.

Moscow pursued a more limited operation in the second phase over the spring and early summer, expanding its occupation of part of southern Ukraine and seizing all of the Luhansk region and parts of neighbouring Donetsk in the east.

But the third phase from August through November has involved a Ukrainian fightback in the north-east and south, regaining most of the territory gained by the Russian military in the first few months.

A Putin victory is now hard to envisage. His “annexation” of four Ukrainian regions is in tatters. Now the question is how far and how fast Ukraine can regain the territory occupied in 2022, and put pressure on areas held by Russian proxies since 2014.

What then for the fourth phase of the war which will play out over winter?

The battlefield

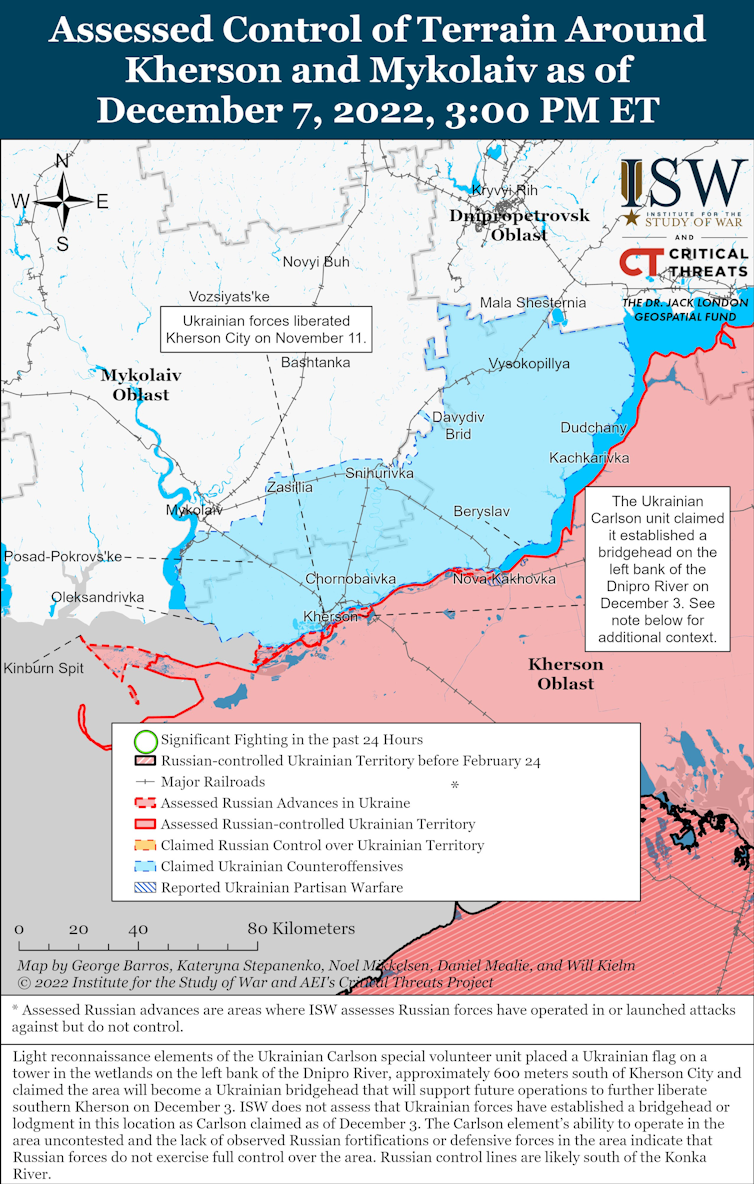

With the liberation of Kherson city, Ukrainian forces hold all areas west of the Dnipro River. The retreating Russian forces are on the east bank, having blown up all major bridges to prevent Ukrainian pursuit. But there are gathering signs of another Ukrainian push. The first troops crossed the Dnipro and established a foothold in a village last week.

The Russians are moving civilians out of some settlements on the east bank, and have reportedly withdrawn some troops as well.

It remains unclear where they will establish their new defensive line. The Ukrainian pattern through the autumn has been to degrade Russian capabilities, through strikes on occupied Crimea as well as eastern Kherson, before advancing on the ground. The strikes have damaged or destroyed bases, warplanes, ammunition depots, bridges and logistics and supply positions.

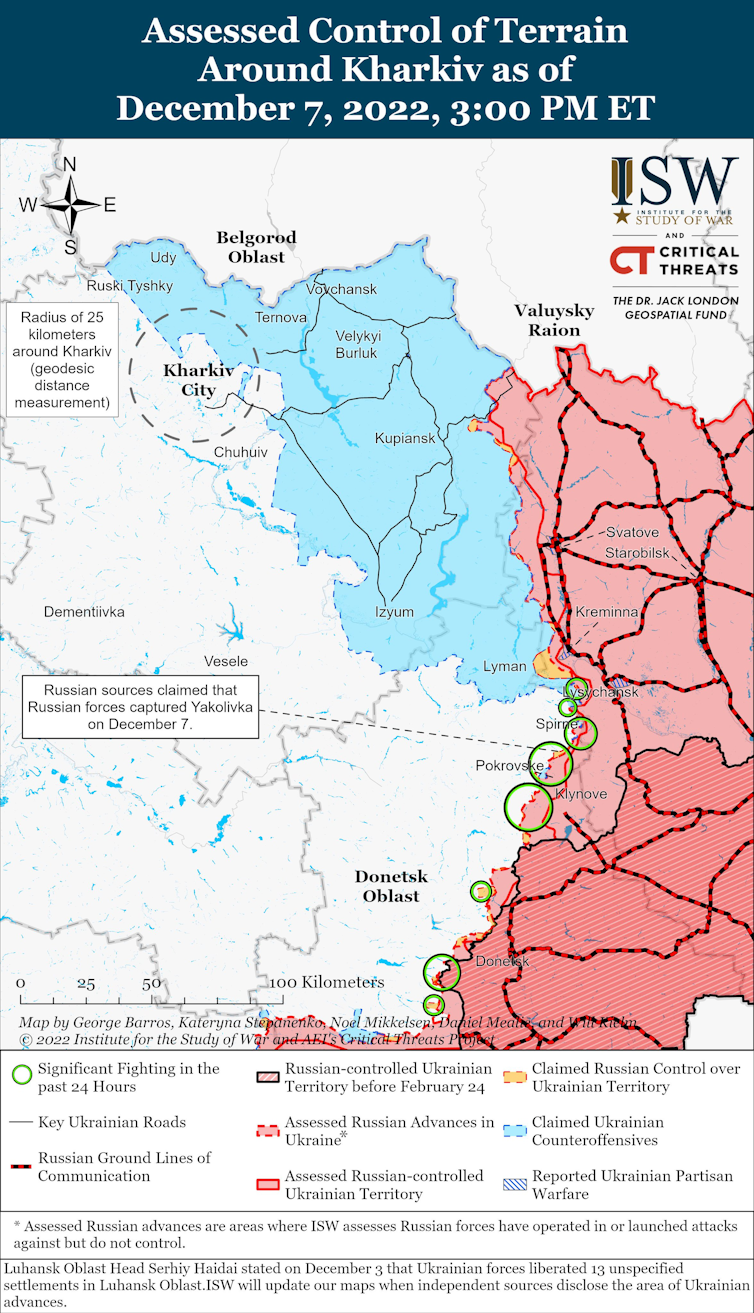

That is likely to be the pattern through the winter as well. The rapid Ukraine advance in September has been followed by a consolidation phase which Russia has tried to disrupt with its persistent shelling. The Russians have also sought for weeks to declare a largely symbolic victory with the conquest of Bakhmut in the eastern Donetsk region.

The fighting has been some of the bloodiest in the war, but a Russian victory would have little strategic value. Bakhmut’s role as the southern end of Ukraine’s defensive line was overtaken by the autumn counter-offensive.

More important is whether Ukraine can break through the Russian lines in the Luhansk region, which would begin to roll back Russia’s summer advance and further erode Russia’s annexation of the four proxy regions.

The energy front

Putin’s last hope of regaining the initiative is to break Ukraine’s energy infrastructure and has escalated strikes since October 10, knocking out up to half of Ukraine’s power grid. But Ukrainian will has not broken amid round-the-clock repairs and emergency and scheduled blackouts.

Now there are signs of Russia’s diminishing capacity to continue this barrage. During the strikes on December 5, for example, just over 70 missiles were launched, more than 60 of which were reportedly downed by Ukrainian air defences. Western officials say the Iranian drones have been exhausted, and Tehran has not agreed to a further delivery. Russia now has a stock sufficient for only two or three more mass attacks, according to Ukraine’s presidential advisor Mykhailo Podolyak.

Meanwhile, Russia has been trying to break European support for Kyiv with the threat of a reduction, or even a complete halt, of energy supplies. It shut down the Nord Stream 1 pipeline and is suspected being behind the explosions damaging both Nord Stream 1 and 2 in the Baltic Sea.

But this energy offensive, as well as the “grain war” has failed to dent western resolve to stand by Ukraine. European countries – individually and through the European Union – have actually stepped up financial and military assistance.

Legal and diplomatic front

On the diplomatic front, there is no prospect of negotiations. Ukraine’s precondition is Russian withdrawal from territory occupied this year. Putin shows no sign of giving up on his ambition for the eventual fall of the Zelensky government and retention of his “annexations”.

But there is also a focus now on justice and accountability for war crimes. The UN and the International Criminal Court are already carrying out investigations in liberated areas. Even more significantly, there is now a sustained effort for Russian leaders as well as individual troops to face prosecution. Zelensky’s call for an international tribunal is now being supported by France and the Netherlands as well as the Baltic States.

European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen said on November 30 that the European Union, with UN backing, will support the special court. A draft UN resolution is being prepared for consideration by the general assembly.

Russian front

Meanwhile, Putin faces pressure on multiple domestic fronts. The Russian economy, now on a wartime footing, is projected to contract by 8% over 2022-2023. Much of the manufacturing sector, such as the automotive industry, is crippled. Russia’s oil revenue is falling, even before this week’s imposition of a price cap by the European Union, G7 countries and Australia.

The Kremlin has cracked down on dissent with detentions and the threat of lengthy prison sentences, but Putin’s mass mobilisation and the Ukrainian advances are spurring discontent within his own ranks as well as the Russian public.

In a November poll by the independent Levada Center, 53% of respondents favour negotiations versus 41% who want to continue the war. An internal Kremlin-commissioned poll was even starker for Putin: 55% favoured peace talks and only 25% wanted a continuation of the war.

Winter is coming – and it’s cold across Ukraine. But the chilly winds of defeat? Those are blowing through Moscow’s Red Square.![]()

Scott Lucas, Professor, Clinton Institute, University College Dublin

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.