Luddites

Capitalism aims to convert ambition to success. Its alchemy of incentives fosters a relentless pursuit of economic opportunity from things we crave: food, shelter, bigger iPhones, desirable mates. Our hunger for wealth and love drives us to work and create — capitalism’s genius is finding new avenues for that drive.

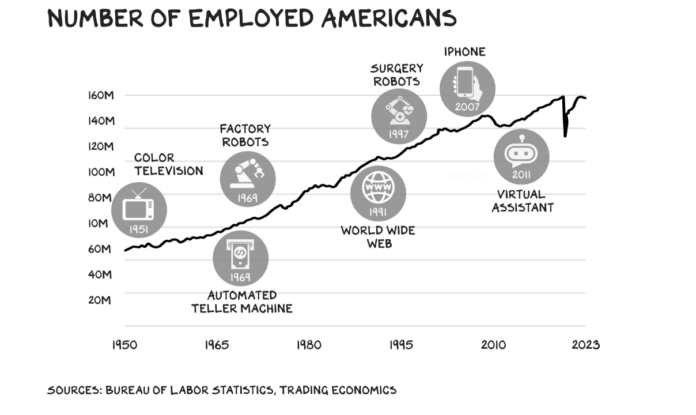

The philosopher’s stone of capitalism is technological innovation. It’s no accident capitalism flourished and spread across the globe contemporaneously with the adoption of new technologies in production, transport, and information. Each technological advance unlocks more space for ambition — new goods, better ideas, richer experiences. And that economic expansion creates more opportunities for ambition. More wealth, more innovation … more jobs. Wash, rinse, repeat.

False Alarm

We relearn this lesson with every technological breakthrough. The latest is artificial intelligence, and in particular, the spectral chatbot ChatGPT. The media’s verdict on AI is already in: “We are about to lose a shit ton of jobs.” Those headlines likely inspired more clicks than “2023 Begins With Unemployment at a 50-Year Low” would have. The latter is true.

They should have interviewed William Lee. In 1589, Lee invented the stocking frame knitting machine, a device that could do the work of several workers. Queen Elizabeth I dismissed his innovation: “I have too much love for my poor people who obtain their bread by the employment of knitting to give my money to forward an invention that will tend to their ruin by depriving them of employment and thus making them beggars.” Despite the Queen’s disapproval, Lee’s design led to the mechanization of textiles, and that led to the organized attacks on textile factories by a secret society of weavers called the Luddites who destroyed every piece of machinery in sight. Parliament (by this point, all in on capitalism) made machine-breaking a capital offense and called in troops. At one point, there were more redcoats fighting Luddites at home than Napoleon in Spain.

The Luddites are gone, but we are still afraid of the machines. Wharton economist Jeremy Rifkin wrote a bestseller, The End of Work, that predicted we would have to radically restructure society, as robots would leave us with nothing productive to do. In 2014 half of workers in technology thought new technologies would be net job destroyers. Andrew Yang’s 2020 presidential campaign was predicated on this notion, and he can point to peer-reviewed research claiming that 47% of U.S. jobs are at risk of automation. Vinod Khosla, the founder of Sun Microsystems, predicted 80% of medical doctors’ jobs would disappear by 2030 due to advances in AI.

Reality Bites

What happened? A: America has more physicians than ever before, and unemployment is near an all-time low. Even if we get an AI MD, 500 years of experience tells us there will be more jobs in health care, not fewer.

It’s not intuitive — a function of our species’ innate inability to think long term. But the reality is that disruptive technologies cause employment instability for only short periods. The market crisply reorganizes itself around the innovation, and job growth increases from there. Countless empirical studies have proven this.

A technology is introduced — say, the car — and an existing sector is made irrelevant overnight (e.g., horse and carriage). In the short term, we’re fixated on how many horses will be out of a job. Harder to imagine, however, is how many jobs the car will create — as well as the different kinds of jobs it will create. It’s hard to envision radios, turn-signal lights, motion sensors, and heated seats. Let alone NASCAR, The Italian Job, and the drive-through window. In other words, disruptive technology results in demand for things we never knew we wanted.

In 1850 farming made up 3 in 5 U.S. jobs. By 1970 that number was less than 1 in 20. From tractors to pesticides to preservatives, technological innovation was the creative destroyer that eliminated most jobs in America. But the void was filled by … everything else. Entire sectors were created that employed tens of millions of Americans.

It’s Like Déjà Vu All Over Again

Here we are again. ChatGPT is impressive, no doubt. “Tell me the origin story of the knitting machine.” Done. “Write a blogpost about AI in the style of Scott Galloway.” Easy. ChatGPT’s peers can also handle many other types of tasks — from digital artwork to software engineering. Together, they will likely render millions of jobs irrelevant. Why hire an artist/copywriter/coder/lawyer when you can license an AI bot for cents on the dollar?

For many companies, the process has already begun. Last week, Buzzfeed announced it would start using ChatGPT to produce content — the stock more than doubled on the news. Meta, Canva, and Shopify are leveraging the technology for their own processes. Microsoft’s bet on ChatGPT is the most significant: $10 billion.

The anxiety for the past couple decades has been over robots and automation. And it’s true that many routine, low-skilled jobs were automated away. What’s also true is that new jobs, again, filled the void. One study found that between 1999 and 2016, automated technology created roughly 23 million jobs in Europe — that’s half the increase in employment during that period. McKinsey estimates that future advances in automation will kill a third of American jobs, and that it will create more than it kills. Specifically: tech jobs, care-worker jobs, building jobs, education jobs, management jobs, and creative jobs. Net-net, technology expands employment.

Softest Landing

Disruptive technology has externalities, including short-term pain for workers on the wrong side of the innovation. During the industrial revolution real wages stagnated for decades while productivity soared. This put many out of work for years, and the civil unrest that followed was understandable. Eventually wage growth caught up, but the interim was not easy. History also teaches us that America has been terrible at acknowledging the pain and allocating some of the gains from increased productivity to worker retraining and support for those affected during the transition.

We can walk and chew gum at the same time — push for technological innovation and aid the people it affects. That means generating stability (i.e. employment) in the short term while the job market recalibrates. The Ancient Greeks understood this: To offset technological unemployment (from rotary mills, gears, water clocks, etc.), Pericles started a government-funded public works program that commissioned many architectural and cultural projects and employed thousands. It also resulted in several masterpieces, including the Parthenon.

We don’t need to build temples, but we can put public money to good use: roads, infrastructure, sustainability projects, etc. I say we start with demolishing, and rebuilding, LAX and Miami International. But I digress. Jeremy Rifkin overestimated the scale of automation’s job destruction, but he wasn’t wrong about its intensity, and some of his ideas, along with those proposed more recently by Andrew Yang, merit attention. The long-term economic gains we’re bound to realize from transformative technologies (including the car, telephone, internet, and AI) should offset short-term investments in social programs and training that offer a bridge. The ROI here is not only a function of maintaining a worker’s productivity, but reducing the costs and despair that can sink a household when a family member not only loses their job, but their sense of purpose. We know technology will continue to bring prosperity. The bigger question is will it bring progress.

Life is so rich,

![]()

P.S. Want to see me lecture about TikTok live? Join the Brand Strategy Sprint starting on February 13. Enrollment closes next Tuesday.