Disinflation

Courtesy of Scott Galloway, No Mercy/No Malice, @profgalloway

-

Listen to This Newsletter: Audio Recording by George Hahn

I’ll do approximately 25 speaking gigs in 2023, down from 47 in 2022. The primary reason for the decline is that I live in London now. Jumping on a plane to Austin to speak at SXSW used to sound fun … now it sounds like jet lag and time away from my boys, who refuse to stop growing when I’m out of town. But that’s not what this post is about. The best part of a speaking gig is the Q&A. The questions are remarkably similar across regions and events. For most of last year the most common questions were about our research on failing young men. Then they changed abruptly, to: “When will inflation come down?”

I have a degree in economics, taught micro- and macroeconomics in grad school, and worked in fixed income at Morgan Stanley. Despite that formal training, it wasn’t until I was in my forties that I appreciated that the economy is more a function of psychology and markets vs. … economics. Also, if you want to opine about the economy, you must acknowledge that nobody has a crystal ball — economists have predicted eight of the last two recessions — and be willing to get it wrong.

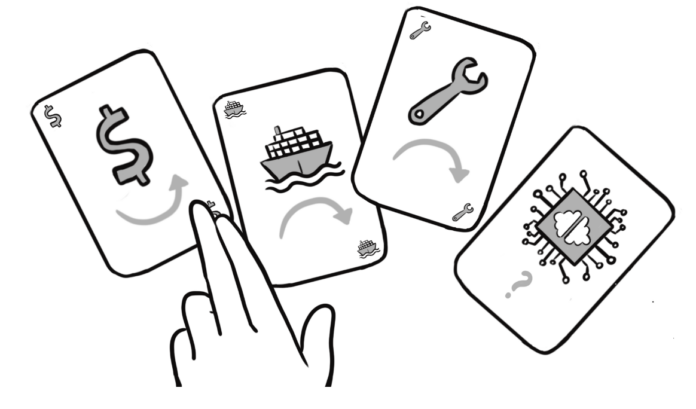

Anyway, in the third quarter of 2022 we predicted on the Prof G Markets Pod that inflation would come down as fast as it had accelerated. (I just read the last sentence and one thought runs through my head: When did I get so boring?) Wrong again. It’s going down faster. Our thinking: Inflation is a supply/demand imbalance — too many dollars chasing too few goods — filtered through our expectations of the future. And as we said six months ago, when inflation was a front-page bonfire, these factors would swiftly realign. And they subsequently have. Inflation is in fact receding, for the same basket of reasons it went up — not math, but markets. Specifically, the market of money (interest rates), the market of goods (supply chains), and the market of labor (employment). Plus, an unexpected chaser: the disruptive potential of AI.

Our thinking: Inflation is a supply/demand imbalance — too many dollars chasing too few goods — filtered through our expectations of the future. And as we said six months ago, when inflation was a front-page bonfire, these factors would swiftly realign. And they subsequently have. Inflation is in fact receding, for the same basket of reasons it went up — not math, but markets. Specifically, the market of money (interest rates), the market of goods (supply chains), and the market of labor (employment). Plus, an unexpected chaser: the disruptive potential of AI.

2%, 4%, Let’s Call the Whole Thing Off

Some inflation is probably a good thing — too little and you risk tipping into “deflation,” which gives economists nightmares. The fear is that people will stop spending in anticipation of lower prices, and economies, like sharks, only survive in motion. In typical fashion, economists don’t agree on how much inflation is good. Many academics and institutions call for an inflation target of 3% to 4%. But central bankers in the U.S. and Europe (i.e. the Federal Reserve) target 2%. In actual business, a 100% disparity between metric targets would be cause for concern, but in economics it’s cause for tenure.

Consumers tend to worry about higher inflation more than economists, who recognize that inflation is at least partially self-correcting. When economist Danny Blanchflower (Dartmouth) was on my Prof G Podcast, he pointed out that inflation has never endured in a modern Western economy. But consumers also vote and spend, so their views carry weight. (This is 51% vibe and 49% science.) What everyone can see with their own eyes is that when inflation hits 8% in a country where it’s been sub-2% for decades, people get excited. So what happened, and why should we all keep calm and carry on?

Interest Rates (aka “This Invisible Hand”)

David Foster Wallace once told a joke about two young fish who run into an older fish. The older fish says, “Morning boys, how’s the water?” The two young fish swim on for a while before one turns to the other and asks, “What the hell is water?”

For several decades, our water has been declining interest rates. Think of interest rates as the throttle on economic risk taking. Low interest rates mean money is cheap and easy to borrow, so people take more risk. The Fed sets the floor on interest rates (the “federal funds rate”), which it took to rock bottom, Crazy Eddie “I’ve gotta move these cars today” levels to get us out of the Great Recession. Soon after the Fed finally began moving them up again, Covid knocked them back down. With the money taps gushing, the stock market ripped, as the cost to finance growth and the value of future cash flows decreased and increased, respectively. We were gamblers at a craps table crediting our resilience and daring, while the casino was pumping pure oxygen through the A/C vents.

Many strange new market phenomena emerged as a result of this new normal: Crypto, SPACs, billionaires flying to “space,” tech workers filming TikToks at their company’s kombucha bar, pet bereavement leave, car companies IPOing on zero revenue, CNBC platforming carnival barkers, VCs doing zero diligence before investing hundreds of millions of dollars in Adam Neumann (again), unprofitable tech stocks quintupling, 50-person Diversity, Equity & Inclusion departments, 30% headcount increases, Cathie Wood. We became DFW’s fish, unaware that cheap money was even a thing. But it was. Because if inflation is too many dollars chasing too few goods (it is) then the free money party would eventually juice prices. There’s only so many crypto scams and boutique grocery delivery businesses we can create each day to soak up all that capital. And when prices did start to rise, the obvious response from the Fed and other central banks was to raise rates. Higher rates, less money flowing into the economy, less demand, slowing inflation. It should be that simple.

We became DFW’s fish, unaware that cheap money was even a thing. But it was. Because if inflation is too many dollars chasing too few goods (it is) then the free money party would eventually juice prices. There’s only so many crypto scams and boutique grocery delivery businesses we can create each day to soak up all that capital. And when prices did start to rise, the obvious response from the Fed and other central banks was to raise rates. Higher rates, less money flowing into the economy, less demand, slowing inflation. It should be that simple.

The Great Ungunking

For nearly half a century, global companies had been squeezing out more and more profit by simultaneously thinning and complicating their supply chains. The Japanese pioneered “just-in-time” manufacturing, where parts and raw materials were ordered to arrive only as they were needed, rather than piling up in warehouses. Then companies from Apple to Walmart supercharged this concept globally, designing intricate webs of parts suppliers and assemblers with minimal excess capacity or inventory across the chain. It worked, but it depended on constant movement throughout the system. Which was awesome until we turned off the volcano — China and nearly every other low-cost manufacturer — in the spring of 2020. The global supply chain had become so optimized that there was no slack or ability to respond to shock. Things ground to a halt.

For a while, it felt as if half the world’s stuff had disappeared. Which it had. Covid kneecapped manufacturing’s ability to make semiconductor chips, which kneecapped tech’s ability to make … tech, and thus, anyone else’s ability to make anything else. Fewer chips meant fewer cars, printers, routers, iPads, and dog-washing machines. It wasn’t just tech. Shopping for home appliances became a SpecOps mission. Remember the baby formula shortage? Me neither. Also: lumber, toilet paper, tampons, and sofas.

By the fall of 2020, 94% of the Fortune 1000 reported supply chain disruptions, and it wasn’t just demand building. Ships were in the wrong place, some warehouses were bursting, sources of supply were coming back online at different cadences, and managers had no idea how to forecast the rate at which demand would return. Plus, China was a mess. And if the 21st century global supply chain spiderweb has a central node, it’s China. The result: All those dollars (see above) had even fewer goods to chase, so prices went up. And this is about psychology as much as reality — nothing makes people freak out about prices like empty store shelves. Retailers were snapping up any inventory they could find, and what was available for sale was sold dear. At one point, space in shipping containers was going for $277 per square foot. The cost of a house in Dallas. Only, you get to keep the house in Dallas.

Once gunked, however, ungunking was just a matter of time, and a lot of shouting over international phone lines and in stressful Zoom meetings. The entirety of the corporate world was motivated to fix these problems, and they were fixable. What remains to be seen is if we will take lessons from this debacle, and make our supply chains less brittle by investing in suppliers closer to home and becoming willing to accommodate more slack (i.e., fat) in the circulatory system. But that’s a different post.

Supply chains are almost back to normal. This is reflected in the data — the global supply chain pressure index has come down more than 75% in the past year, trade through America’s West Coast ports has risen 25% from pre-pandemic levels, and semiconductor chips are “no longer in a shortage zone.” Also, more baby formula.

Take This Job and … on Second Thought

The largest market is the market for time. The labor market is the market that underpins everything else; it’s where we get the money to create the demand and how we make the goods to supply it.

Once we pulled back from the drop in employment during the depths of the pandemic, there was a hot minute where labor had the upper hand over capital. That’s not the normal state of affairs — it’s called “capitalism” after all, not “laborism.” (Note: Any claim that market dynamics will sustain a middle class without massive investments is trickle down/on bullshit.) Anyway, imagine trying to explain to someone before March 2020 that large portions of the workforce would suddenly refuse to come to the office, and that they’d still … keep their jobs.

In the information economy, the balance between capital and labor likely swung too far toward labor. Wall Street bankers decided they could do Zoom meetings and proofread deal docs at Starbucks. Big Tech was particularly under the gun, offering not just larger and larger pay packages, but a raft of perks (e.g. valet parking, red-wine-braised short ribs, and free blankets), while loading up on employees — all of which created upward pressure on wage inflation.

Then things changed. First, Apple added opt-in tracking to iOS, threatening the ad-supported ecosystem. Then, the impact of less free money and a return to supply chain normalcy freed up the natural business cycle, and companies (and their shareholders) realized they couldn’t keep increasing their headcount 20% each year. The balance between capital and labor in the growth economy has reverted. Tellingly, these layoffs have largely been confined to tech, a relatively small portion of the economy the media covers obsessively. Perception bests reality when headlines report a five-figure layoff every week, and nobody does the math on the broader employment picture. One of the great externalities in society is an ad-supported ecosystem that turns attention to capital, resulting in a catastrophizing of all media.

The chaser dropped on November 30, when every knowledge worker (reportedly) met their replacement: ChatGPT. With more than 30 million users, ChatGPT is arguably the fastest growing product in history. (The iPhone sold 6 million units its first year; granted, they cost $499 each and ChatGPT is free.) I used to say about WFH that if your job can be done from Boulder, it can be done from Bangalore. Well, in 2023, the new Bangalore may be ChatGPT.

Inflation is about supply, demand, and psychology, and the psychology of ChatGPT is that it may not be a good time to quit your job. Unless, of course, you’re joining an AI startup. History tells us the innovation in AI will likely create more jobs than it destroys.

Deflated Outlook

Lately, I’ve been struck by how negative young people are about the future. The aforementioned dark-colored glasses of the media, and legislative policy that has transferred wealth and opportunity from young to old, have broken the fundamental compact our society has had with its youth: At 30, you will be doing better than your parents when they were 30.

The poor outlook on the world young people share is understandable but not accurate. Opportunity and injustice have increased and decreased dramatically, respectively. What we lack is the leadership to ensure our immense prosperity is shared with a younger generation who have registered a wealth decline in the face of historic growth in productivity. Despite this, women in Iran, Ukrainian soldiers, and an increasingly diverse cohort of young citizens see a better future that is within their grasp and worth fighting for.

Much of the pessimism in our society stems from contrasts. Specifically the contrast between our ability to achieve the remarkable and our inability to offer the obvious. We can peer into the beginning of time, re-create the sun, and manufacture vaccines against cancer, yet the U.S. can’t seem to figure out affordable child care or housing. A nation’s well-being is correlated to prosperity that translates to progress for its citizens. Since the year I was born, China’s life expectancy has increased from 47 to 77. In the U.S., we’re long on genius but short on empathy.

Life is so rich,

![]()

P.S. If you’re a team leader, consider bringing your team to sprint together at Section4. We’ll make your team more strategic and more engaged (and give you some coaching time back). Request a demo or email teams@section4.com.