With Iran purportedly capable of making a nuclear bomb in a matter of months, what will its leaders do next?

By Amin Naeni, Deakin University

The on-again, off-again talks between Iran and western powers over Tehran’s nuclear program have stalled yet again due to disagreements between the two sides.

US Secretary of State Antony Blinken has blamed Iran for “killing an opportunity” to come back to the negotiating table and maintained the talks were no longer a priority for the Biden administration.

Iran, meanwhile, seems to be inching closer to being able to actually build a nuclear weapon.

Inspectors from the International Atomic Energy Agency have said Iran had enriched uranium up to 84%, just short of the 90% required for a bomb.

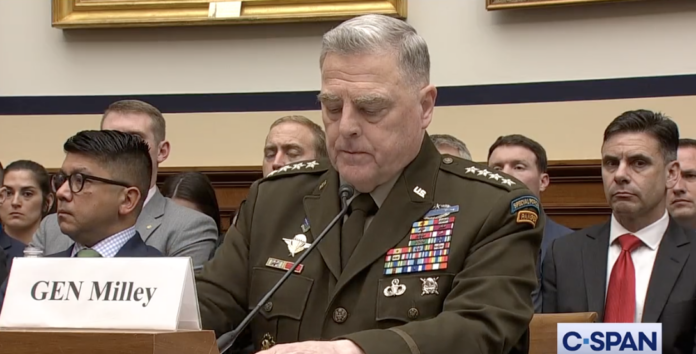

And General Mark Milley, the US chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, told Congress in late March that Iran could have enough fissile material to make a bomb in “less than two weeks” and a nuclear weapon itself within several months.

Given these developments, is there any room left for an agreement?

.@thejointstaff Chair Gen. Mark Milley: “Iran could produce enough fissile material for a nuclear weapon in less than two weeks, and it would only take several more months to produce an actual nuclear weapon.” pic.twitter.com/DZijgSUcXW

— CSPAN (@cspan) March 29, 2023

Tunnel vision on nuclear talks

Over the past two years, both the US and European Union have been resolute in their efforts to revive the nuclear deal that had been scrapped by then-US President Donald Trump in 2018, known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA).

However, Western attempts have yet to bear fruit, reportedly due to the “maximalist demands” made by the Iranians, including removing the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps from the US list of foreign terror organisations.

Despite this, the EU believes the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action remains “the only way” for addressing Iran’s nuclear program. The US, despite de-prioritising the talks, is also not willing to officially announce the death of the deal.

This tunnel vision, however, seems to ignore the changes that have taken place since 2015, as well as the more general pattern of decision-making in Iran.

Although backers of the deal often argue it has significantly restricted Iran’s nuclear capabilities, Tehran’s nuclear program has actually expanded in just two years. And recently, a news outlet affiliated with the Revolutionary Guards made it clear that Iran cannot “close its doors to the scientific methods of making a bomb for rational reasons”.

Now, the big question is what Iran’s leaders will do next. The CIA director, William Burns, said in February that he believes Iran’s Supreme Leader has not yet made a decision on building nuclear weapons.

So, what is the Iranian leadership thinking? To answer a question like this, the pattern of decision-making in Iran’s history is a critical factor that has widely been ignored.

.@margbrennan: “Have Iran’s leaders made the decision to pursue a nuclear weapon?”

CIA Dir. William Burns: “To the best of our knowledge, we don’t believe that the Supreme Leader in Iran has yet made a decision to resume the weaponization program…” pic.twitter.com/b5vnO8TGjs— Face The Nation (@FaceTheNation) February 25, 2023

A history of painstaking deliberations

Since the 1979 revolution, Iranian leaders have exhibited a cautious and slow approach to making major decisions.

This protracted process of decision-making in Iran is rooted in anxiety about the long-term survival of the regime, which has been grappling with a range of internal and external threats over the past four decades.

For instance, it took eight years for the Islamic Republic to accept the ceasefire and peace talks with Iraq following their war in the 1980s.

In addition, Iranian authorities took a decade to be ready for serious negotiations on a nuclear agreement with the US and other global powers, following the disclosure of the country’s nuclear program in 2003.

Moreover, while Iran first suggested a “look to the East” policy in the mid-2000s under then-President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, the country didn’t begin developing major policies in this direction until 2015. This has included military cooperation with Russia in both Syria and now Ukraine and a long-term economic, military and security agreement with China.

However, building nuclear weapons would certainly be the most consequential strategic decision by the Iranian leadership since the 1979 revolution.

What the West can do?

So far, the slow process of decision-making in the Iranian leadership has played a significant role in hindering the weaponisation of the nuclear program.

And this limitation of the leadership could provide western powers with an opportunity, given the ongoing protests currently roiling the country.

The months-long protests erupted following the death of a woman in the custody of the morality police last year, hastening the decline of the regime’s legitimacy inside the country and bringing new rounds of sanctions from the international community.

If western countries abandon their obsession over the revival of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action and continue to support the Iranian people in their protests through diplomatic and economic pressure, it will send a powerful signal to Iran’s leaders: the threats to the regime’s existence are not limited to military factors, but also increasingly come from within the country.

It is important to note that amid the protests, Iranian officials and hardliner media have frequently stressed the nuclear deal is not dead and negotiations are ongoing, even though most of them had previously opposed any deal with the West.

This indicates the Islamic Republic would not be ready for the risks that the demise of the nuclear talks could bring – namely, even fiercer protests from the public if it caused another economic shock.

Therefore, the longer the balance of power between the Iranian people and government remains unsettled, the more unlikely it is the regime will make a firm decision on nuclear weapons in the near term.

Consequently, this will provide the West with powerful leverage to secure a more robust and effective agreement in the long term.![]()

Amin Naeni, PhD candidate at Alfred Deakin Institute for Citizenship and Globalisation, Deakin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.