While some are stressing out about tonight decision by Moody’s to redirect its impotence at downgrading the US (as S&P and Fitch have already done) over fears of retaliation by the Biden admin, and instead cutting the credit ratings for 10 small and midsize US banks and saying it may downgrade major banks such as U.S. Bancorp, Bank of New York Mellon, State Street and Truist as part of a “sweeping look” at mounting pressures on the industry, the reality is that rating agencies are a 12-120 month backward looking indicator, and by the time the point to something it’s far too late to trade on it, and if anything one should take the other side of the trade.

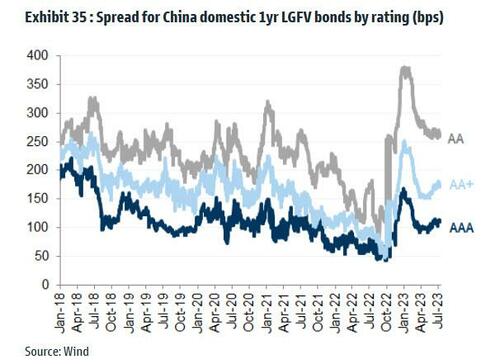

Instead, those looking for leading market stress catalysts should turn their attention to the latest news out of China, where credit stress is once again exploding as a record number of local government financing vehicles (or LGFVs, also considered the currently most aggressive form of Chinese shadow banks) are openly cracking with a record number missing payments on a popular type of short-term debt last month.

A total of 48 LGFVs were overdue on commercial paper, which typically carries a maturity of less than a year, up from 29 in June, according to a Huaan Securities report citing data from the Shanghai Commercial Paper Exchange. Their missed payments amounted to 1.86 billion yuan ($259 million), more than double the 780 million yuan in June.

The revelation, according to Bloomberg, is set to aggravate concerns about the financial health of LGFVs, which are mostly tasked with building infrastructure projects that may take years to generate investment returns (think the more politically correct form of Chinese ghost cities). While none of them has defaulted on a public bond, their repayment risk has come under renewed scrutiny after China’s state pension fund recently advised asset managers handling its money to sell some notes including those from riskier LGFVs.

The report also sheds light on regional areas that have had the highest cluster of LGFVs to stumble on such debt in the past few years: in data current through July this year going back to August 2021, the eastern province of Shandong accounted for 37 of the 140 LGFVs that have missed commercial paper payments in that period, followed by 21 from Guizhou, its impoverished peer in the southwest.

It’s not just commercial paper however: a few months ago, we reported that according to research from GF Securities there were 73 cases of shadow-banking defaults in the first four months of 2023, already a full-year record since data became available in 2018.

“Missing payments in shadow banking are a signal that debt risks in a certain region have become more prominent,” GF analysts led by Liu Yu wrote in a report.

China’s LGFVs had 13.5 trillion yuan ($1.9 trillion) of bonds in total outstanding as of end-2022, or almost half of the nation’s non-financial corporate notes, data from Moody’s Investors Service show.

Steps by authorities “to lower LGFV debt risks will not fully resolve long-term issues,” and their refinancing ability depends on investors’ confidence in government support, especially in weaker provinces, Moody’s analysts led by Ivan Chung wrote in a report.

And judging by the number of CP dominoes falling, investors confidence in LGFV is about to evaporate, giving the government no other choice but to step in and stabilize this critical spoke of China’s infrastructure funding. Because while Beijing may be willing to risk a record 21% youth unemployment rate without a major stimulus, once the CCP faces the double threat of an angry middle class and crashing infrastructure spending, not even China’s record debt to GDP will be enough to prevent Xi from going all in on yet another massive – and globally reflating – stimmy.