With yet another government shutdown looming (money is projected to run out Sept. 30), echoes of panic are beginning to reverberate throughout the mainstream media and Washington DC over the possibility of yet another government shutdown.

But before anyone burns their hand on the stove again, Goldman’s Alec Phillips puts the potential fallout in context.

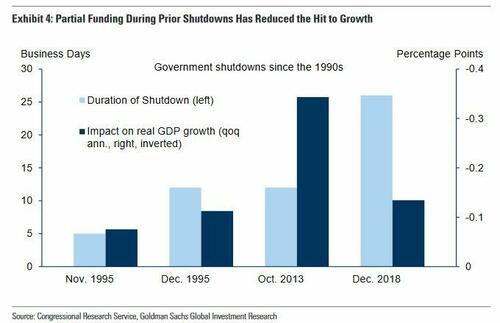

In a nutshell – since the rules for government spending under a shutdown are clear, and shutdowns have occurred in the past, the economic hit is more predictable. And while federal spending is equal to almost a quarter of GDP, the impact of a shutdown is much smaller, for four key reasons:

-

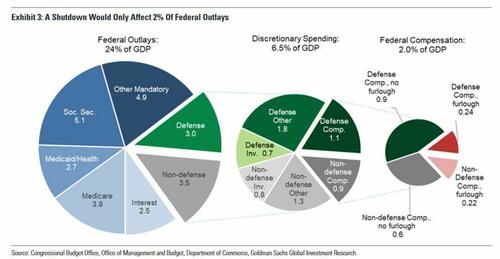

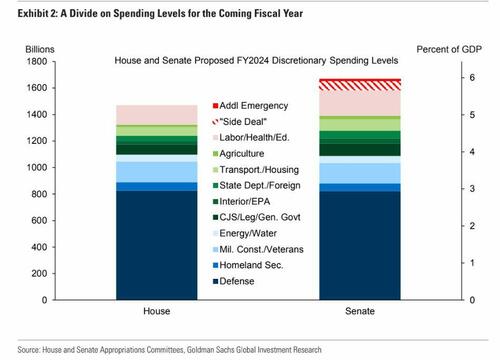

It’s All About the Discretionary Spending: Federal outlays are broadly categorized into discretionary spending (like defense), mandatory spending (Medicare, Social Security), and interest on public debt. Only discretionary spending takes a hit during a shutdown. This represents around 6.5% of GDP.

-

Not All Departments Are Created Equal: Depending on the funding approved by Congress, some departments may remain open while others shut down. Prolonged shutdowns have often spared the Department of Defense, which accounts for roughly half of discretionary spending. This time around, since none of the 12 standard appropriations bills have passed, the shutdown would be across the board, but still limited to discretionary areas.

-

Low Impact on Investment and Goods: Shutdowns mainly affect federal employment rather than investment or purchases of goods and services. Federal pay is roughly 2% of GDP, and a shutdown would primarily result in reduced work by federal employees, thereby affecting only about 0.5% of GDP.

-

Most Federal Employees Would Still Be Working: Out of 2.3 million civilian federal employees, approximately 800k would be furloughed. Essential services continue, and active-duty military personnel would remain in place.

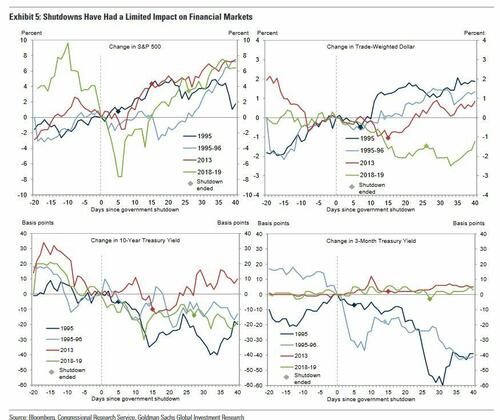

What’s more, market reactions to government shutdowns have become increasingly muted given that despite the high odds of a shutdown, funding typically arrives at the 11th hour via a “continuing resolution” to provide temporary funding at the start of the Oct. 1 fiscal year, which eventually translates to longer-term spending bills. A failure to do either leads to a shutdown – which looks likely at this point.

And while a shutdown would likely ‘briefly hit consumer confidence,’ given the modest economic and market effects, it would have little effect on monetary policy unless it’s a prolonged shutdown starting in October, in which case there’s an incremental addition to the argument that the FOMC might stay on hold at its November meeting (as Goldman expects). In the past, the FOMC has downplayed the economic impact shutdowns – focusing instead on the potential impacts to the reporting of economic data.

As Phillips notes;

A government shutdown looks more likely than not later this year. At the start of the year we noted a good chance of a government shutdown and made it the base case following the debt limit deal in June, in light of the thin House majority and disagreement on spending levels. The odds of a shutdown appear at least as high now as they did then.

A shutdown occurs if Congress fails to pass annual spending bills. Funding typically comes first via a short-term “continuing resolution” to provide temporary funding at the start of the fiscal year (Oct. 1) and then eventually through full-year spending bills. A failure to pass either leads to a shutdown.

Prior shutdowns have occurred either due to disagreement on the level or distribution of spending, or a dispute over extraneous issues that one party wants to address in spending legislation. At the moment, both types of risks are in play.

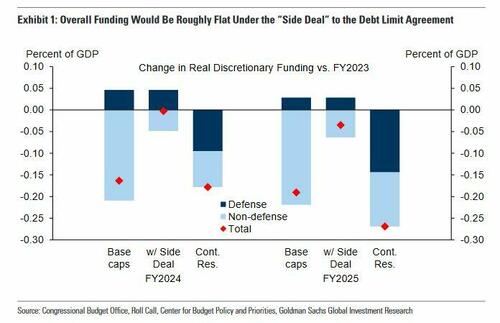

In theory, the “Fiscal Responsibility Act” (FRA) Congress passed in June to raise the debt limit should have ended the debate on spending levels. The FRA included three relevant provisions:

1. Spending caps limit funding for FY2024-25. If Congress appropriates above the caps, across-the-board cuts (“sequestration”) bring spending back down. While the caps limit spending, Congress must still pass spending bills to provide the funding.

2. A “side deal” to the FRA would allow Democrats to add back most of the non-defense funds that would be cut under the caps deal. However, Congress must still pass spending bills to effectuate these changes.

3. An automatic cut to 1% below the FY2023 level takes effect if Congress has not passed all 12 full-year spending bills before Jan. 1, 2024 and is still operating under a continuing resolution. As shown in Exhibit 1, defense would be cut below the caps, while non-defense would rise slightly above the capped level, but would still represent a modest cut compared to the “side deal”.

* * *

Of note, last week House Speaker Kevin McCarthy floated a short-term government funding bill to avoid shutdown this fall, according to NBC News.

He [McCarthy] believes Congress will have to pass a short-term government funding bill to avoid a shutdown this fall, two sources with knowledge told NBC News.

The remarks reflect a growing recognition that Congress doesn’t have enough time to reach a full-year funding deal before money runs out on Sept. 30. Lawmakers are on a monthlong August recess and return in September, just a few weeks before the deadline.

While McCarthy now privately agrees Congress needs to buy time to reach a funding deal, it’s not clear how much they’ll push for. One Republican lawmaker said McCarthy, R-Calif., indicated he didn’t want to set a deadline that pushes Congress up against the Christmas holiday. A second GOP source didn’t recall McCarthy specifying a length of time for the stopgap bill.

In short, according to Goldman, the chances of at least a brief shutdown occurring are high, but its impact is expected to be limited and largely reversible.