Alabama’s defiant new voting map rejected by federal court — after Republicans ignored the Supreme Court’s directive to add a second majority-Black House district

By Henry L. Chambers Jr., University of Richmond

In a rebuke of the Alabama legislature, a panel of three federal judges rejected on Sept. 5, 2023, the state’s proposed voting districts that failed to create a second district where Black voters could elect a political candidate of their choice.

In rejecting the legislature’s proposed voting districts for the second time since 2022, the federal judges wrote they were “deeply troubled” that Alabama lawmakers submitted a new plan that did not adhere to previous court rulings, including one issued by the U.S. Supreme Court on June 8, 2023.

“The law requires the creation of an additional district that affords Black Alabamians, like everyone else, a fair and reasonable opportunity to elect candidates of their choice,” the three judges wrote, adding that the state’s new plan “plainly fails to do so.”

For the 2024 elections, the judges have assigned court-appointed experts and a special master to draw three potential maps that each include two districts where Black voters have a realistic opportunity of electing their preferred candidate. Those redistricting proposals are due to the court by Sept. 25.

Alabama officials have denied any wrongdoing and said their proposed voting districts, including one where the percentage of Black voters jumped from about 30% to 40%, were in compliance with recent federal court rulings. The state is expected to appeal the panel’s latest ruling to the U.S. Supreme Court.

“We strongly believe that the Legislature’s map complies with the Voting Rights Act and the recent decision of the U.S. Supreme Court,” Alabama Attorney General Steven Marshall, a Republican, said in a statement. “We intend to promptly seek review from the Supreme Court to ensure that the State can use its lawful congressional districts in 2024 and beyond.”

A surprising decision to protect Black voters

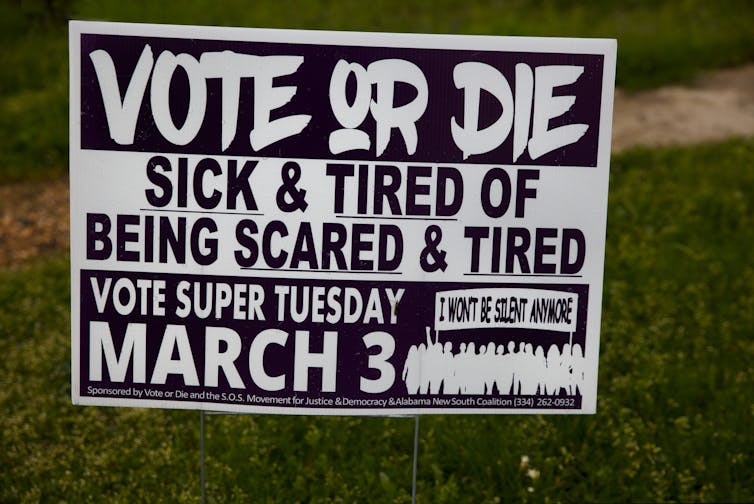

At issue in the Alabama case was whether the power of Black voters was diluted by dividing them into districts where white voters dominate.

After the 2020 census, the Republican-controlled Alabama legislature redrew the state’s seven congressional districts to include only one in which Black voters would likely be able to elect a candidate of their choosing.

Black residents comprise about 27% of the state’s population, and voting rights advocates argued that their numbers suggest they should control two congressional districts.

In its surprising ruling on June 8, the U.S. Supreme Court jettisoned Republican-drawn congressional districts in Alabama that a federal district court in Alabama had ruled in 2022 discriminated against Black voters and violated Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

The court relied on a nearly 40-year-old, seminal case, Thornburg v. Gingles, that determined a state should typically draw a majority-minority district if three conditions are met:

First, if the racial minority can be a majority in a reasonably drawn district. Second, if the racial minority is politically cohesive, meaning that its members tend to vote together for the same candidates. And third, if the racial minority faces bloc voting by a racial majority that tends to defeat the racial minority’s candidate of choice.

All three conditions were true in Alabama, and the totality of the circumstances suggested minority voters did not participate equally in the political process in the area.

In his opinion, Chief Justice John Roberts explained how racially motivated voter suppression in the century after the Civil War led to the initial passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

While the Supreme Court did not explicitly order the state to create a second majority-Black congressional district, Roberts made it clear how he viewed the long history of racist voter suppression in Alabama – and what factors should weigh prominently in the state’s new political map.

“A district is not equally open,” Roberts wrote, “when minority voters face – unlike their majority peers – bloc voting along racial lines, arising against the backdrop of substantial racial discrimination within the State, that renders a minority vote unequal to a vote by a nonminority voter.”

Given the Supreme Court’s recent history of restricting rights protected under the landmark Voting Rights Act of 1965 – and Roberts’ past opposition – Roberts’ opinion surprised many civil and voting rights advocates.

“States shouldn’t let race be the primary factor in deciding how to draw boundaries, but it should be a consideration,” Roberts wrote. “The line we have drawn is between consciousness and predominance.”

What Alabama did

In its case before the federal panel, the state argued that its proposed map complied with the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and the Supreme Court decision.

State lawyers further argued that the legislature was not required to create a second majority-Black district if doing so would require ignoring traditional redistricting principles, such as keeping communities of interest together.

In its decision on Alabama’s redistricting, the Supreme Court upheld laws that were designed to protect minority voting power for the last nearly four decades.

The same is true with the three-judge court’s ruling on Sept. 5, 2023.

It reaffirmed the legal doctrine that requires jurisdictions to draw majority-minority districts in a narrow set of circumstances in which failing to do would leave minority voters unable to protect their interests through their voting power.

Given Alabama’s long-standing history of suppressing the votes of its Black citizens, the Supreme Court may not have written its last word on race and redistricting in this case.![]()

Henry L. Chambers Jr., Professor of Law, University of Richmond

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.