Think Bigger

-

Audio Recording by George Hahn

Last week, after five months of striking, the Writers Guild (WGA) and the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP) reached a tentative agreement. “We can say, with great pride,” the WGA wrote, “that this deal is exceptional — with meaningful gains and protections for writers in every sector of the membership.”

Five months ago I compared the writers to the British coal miners of the ’80s, predicting they’d exit these negotiations severely impaired. I received a lot of “feedback” (“I hope you die,” etc.). Good stuff. So here we are. Headlines universally lauding the “historic deal” and “victory of human over AI.”

Unexceptional

The WGA is claiming victory as it has no choice. (Imagine declaring defeat after subjecting your constituents to five months of no pay.) So let’s put the ketamine down and acknowledge this is no victory.

The key issue in this debate was money. Specifically, the writers wanted more of it. Adjusted for inflation, the average writer-producer salary has declined 23% in the past decade. Last year, when prices rose as much as 8%, TV writers received a nominal pay increase of 2.25%.

So the WGA made a reasonable demand: a 6% pay bump. But last year, prices rose (I repeat) 8%. In other words, the WGA arrived at the negotiating table demanding a decline in purchasing power. And then … didn’t get what they asked for — they settled for 5%. Meanwhile the striking UAW have rejected an offer of a 20% increase, and asked for 40%.

To be fair, the deal includes pay escalations of 4% and 3.5% in years two and three, respectively. However, to keep up with inflation over the past three years (since the last contract was struck), the writers would have needed a 10% increase in year one. The new deal also includes an increased contribution to health and pension benefits of 1% and overseas royalty payments that, from my vantage, are purposefully opaque and wordy enough to give members enough psilocybin to hallucinate that there’s a there there.

The already ugly math gets hideous when you factor in the five months in which the writers, as a function of the strike, registered a 100% reduction in pay. For a three-year union contract to compensate for those losses, you would need to increase writer pay (again) by 14%. That’s in addition to the inflation losses. So the minimum increase the writers need to not lose purchasing power is 24%.

My favorite jazz hands in the agreement is writers get a 50% royalty bump if their show is viewed by 20% of the platform’s subscribers. Yes, and I’m giving my employees a 50% bonus every time the Jets win the Super Bowl. Sure, it’s happened … just not that often. The series finale of Succession registered three million viewers, i.e., 6% of HBO’s 50 million subscribers.

The Good Stuff

The WGA did secure a couple meaningful gains. As in two. First, there is now a minimum staffing requirement for writers rooms, which translates to more employment opportunities for young writers. Second, they’ve raised the minimum number of weeks studios must employ writers for shows. In other words, work lasts longer. These concessions are meaningful and reflect well on the guild’s commitment to investing in the craft and nurturing talent.

Follow the Mouse

This whole process, however, was a distraction from what the writers, actors, and all workers in the creative community should be focused on. Henry Kissinger once said of my industry: “The reason that university politics is so vicious is because stakes are so small.” The same holds true in media.

Last week I spoke with a group of Hollywood executives and writers. (I’m trying TV for the sixth time.) They were concerned about the strikes — but more concerned that their stalwart, the House of the Mouse, has transformed into a distressed asset practically overnight. Disney stock is at a nine-year low. Subscriber losses continue to mount, with a 7.4% decline in Disney+ subscriptions in the most recent quarter. Operating profits from the cable assets have been halved, and the company’s operating margins are down 75%.

It’s not just Disney. Revenues are falling at Warner Bros. Discovery, Comcast, and Paramount. Last month, cable and broadcast fell below 50% of total TV viewing for the first time in history. Meanwhile, the industry is becoming increasingly reliant on a ventilator of recycled content. All 10 of the highest-grossing movies from last year were repurposed from existing IP. Pixar’s biggest movie was Lightyear (the sixth installment of the Toy Story franchise), and the hot news in TV this week is Greg Daniels has a new show called The Office. I.e., a reboot of the reboot.

The writers can keep fighting for a larger slice of the pie, but the pie gets smaller every day. The WGA will have 15 milliseconds of fame before it starts digging through the rubble searching for remnants of its industry. The question they should ask themselves: What would a “meaningful gain” actually look like, and how do we achieve this? Is it really a 6% pay bump? More transparent residuals? A staffing minimum for writers rooms, striking against impaired companies? To achieve a truly exceptional outcome, the writers, the studios, the executives — everyone in Hollywood must do one thing: Think bigger.

Falsely Convicted

Fixing the problem means first identifying it. The adversary isn’t a Hollywood executive in a cashmere sweater; it’s a 17-year-old kid in a basement scrolling TikTok. The rise of social media is directly correlated with the decline of traditional media. TikTok now commands 95 minutes of user attention per day, equivalent to four and a half episodes of The Office. More than 200 billion Facebook and Instagram Reels are played every day — up 50% in less than one year. YouTube, a subsidiary app owned by Google, now rakes in as much revenue as Netflix.

The ad dollars Hannah Montana used to generate have not been shoplifted by Bob Iger, but Silicon Valley and Beijing. When queried whether they’d prefer TikTok vs. all streaming media, two-thirds of people under the age of 25 choose TikTok. There are between 300 million and 400 million creators on TikTok — their compensation is approximately $40 for every million views. None have ever threatened a strike. The result? A: The company’s valuation is roughly equal to Disney and Netflix combined.

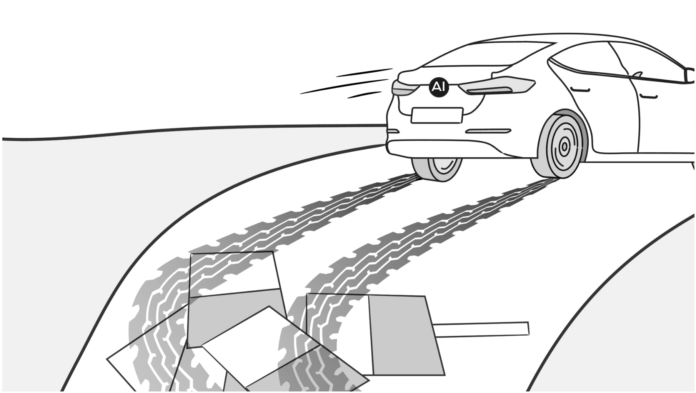

It’s also no coincidence that the year of the writers’ strike is also the year of AI. AI was a core issue in the dispute. The writers (rightly) fear it could replace them and demanded the studios not use AI — which the studios (also rightly) declined. Instead, they met halfway: The studios can use AI, but the original writers must receive credit and compensation. This reflects a misunderstanding of AI. It’s not AI who will take your job, but a writer who leverages it.

Pennies vs. Benjamins

The industry is quarreling over pennies, instead of pursuing Benjamins. More market value in the Nasdaq was created in the first half of this year than in any six-month period in history. The catalyst was AI. The day Microsoft announced it was incorporating AI into its Office suite, it added the value of Disney. The day Morgan Stanley praised Tesla’s Dojo supercomputer, Tesla added the value of BMW. Meta’s new AI-powered recommendation algorithm drove a 24% increase in Instagram use this year. AI has inspired a tsunami of shareholder value: In 2023 alone, Google, Meta, Nvidia, Microsoft, Apple, and Amazon have registered a combined increase of $3.2 trillion.

Compare that to traditional media: The combined market cap of Comcast, Netflix, Disney, Warner Bros., Paramount, Fox Corp., and News Corp. is less than $600 billion. Think about that. The value gained by six tech firms this year is nearly six times greater than the current value of the seven largest mass-media companies put together. Hollywood needs to put down the slingshot, and go big-game hunting.

The Rapture, Pt. 2

As I’ve written before, the fastest way to build wealth is to monetize infrastructure others built for free. Amazon built a thick layer of innovation on top of a free enterprise plug-in called the U.S. postal system. Tesla leveraged green government tax credits to build an EV empire. Google struck the rare earth mineral that is user-generated data, mined it relentlessly at zero extraction cost, and placed banner ads on top of it.

AI is the resurrection of this business model, and the fuel is original content. Yesterday I discovered two of my books, The Algebra of Happiness and The Four, have been used (without my approval) to feed generative AI. I have not been credited or paid. I’m not alone. Last week, writers John Grisham, Jodi Picoult, and George R.R. Martin sued OpenAI for stealing their IP to train its algorithm. Before that, a group of artists sued Stability AI for using their content to generate AI art. So did Getty Images. I used to think tech companies loved user-generated content because most user-generated content isn’t protected by copyright law. (How many TikTokers are claiming IP rights on “day in the life” videos?) But now tech companies are taking it a step further. Now they’re harvesting content that is protected.

There is slow, if not steady, progress on this front. I also discovered I am a class member in a suit that includes all copyright holders whose work has been used in training. That Grisham suit is also a class action, but the class is fiction writers. To date, Big Tech has been hiding behind a complex generative AI algorithm too sophisticated for mere mortals to attribute credit for distinct IP.

These and future suits are important, really important. Hollywood won’t fall because Bob Iger or David Zaslav are greedy. It will fall because Silicon Valley stole the only asset that can truly differentiate generative AI: other people’s content.

What to Do

When I was on the board of The New York Times Company, two thirds of revenue came from ads. During the print days, it worked — we had strong control over distribution and could price ads on terms that made sense for the business. Then Google offered us what looked like a good deal: Let us crawl your content, and we’ll drive traffic to your website in return. More ad views, great right? Spoiler alert: not great.

So while Larry and Sergey were capturing our ad dollars, I proposed we form a consortium (NYT, News Corp, Condé Nast, Hearst, etc.) to block Google’s crawlers and have an auction for the license to our content. I believed Google and a somewhat relevant Bing (see above: 2008) would have paid billions. The board said no, and we missed the chance to upend the business model, to put creators — journalists, editors, artists — in the position of power, instead of the platforms. Soon enough, it was too late.

Consortium

This is that moment again. A world-changing technology has emerged, and we have the chance to write the rules so that we (creators) can make money from it. Notice how quiet Big Tech leaders have been throughout this process. Why? Because they see dead people. In this case, dead people are Hollywood studios and the creative community removing their heads from their asses, binding together, and transforming their assets into potentially trillions of dollars of shareholder value.

To garner an increase in compensation that is legitimately “exceptional,” the writers and the studios/executives/actors/publishers/networks must band together. They should form a consortium, file suits demanding Big Tech and AI respect their IP, license this IP, and start valuing their work. And they should do it as soon as possible. I’d suggest WME be charged with assembling the first 100 members and Barry Diller heads the new consortium. He knows everyone, understands the industry, is smart, and (most importantly) tech is scared of him. This would be infinitely more meaningful than the jazz hands of additional royalty payments for writers on The Last of Us.

Barely keeping up with inflation, minimum number of writers, 1% increases in pension contributions … Jesus Christ, think bigger.

Life is so rich,

![]()

P.S. This week I had my friend Ian Bremmer back on the Prof G Pod to discuss Ukraine, China, and AI — listen here.

P.P.S. I’ll be speaking with the “godfather of AI,” Dr. Yoshua Bengio, on the ethics of AI in November. Sign up now as spots will go fast.