A source of capital has morphed to a source of entertainment. A reality show, minus hot people and Andy Cohen. The charismatic carnival barkers on CNBC serve up a steady diet of SPACs, social media, and space, and would have you believe that’s the center of the economic universe. It’s not. Of the 310 SPACs launched in the past three years, 10 have registered positive returns. It’s a head fake, as the deeper story goes ignored. The traditional IPO construct is in structural decline, and that’s a symptom of a fundamental shift in the capital markets.

4 IPOs and a Funeral

Blue Apron, the home-meal-kit delivery company, sold itself to Wonder Group for $103 million. Which feels like a victory for a business that delivers cardboard boxes of chicken and kale to millennials until you realize this was its last stop on a tour that included an IPO at a valuation of $2 billion. (BTW, I predicted this six years ago.)

Similarly, Instacart, which delivers chicken and kale to millennials in green plastic bags (innovation), went public this month at $10 billion … following a 2021 private-round valuation of $39 billion. Since then the company has lost value almost every day, bumping against $7 billion as I write this. Consumer “tech” firms Rent the Runway and Allbirds are each down 96% from their IPOs. Warby Parker has outperformed, losing only three-quarters of its value.

This follows the June IPO of Cava (it asks millennials to leave the house for chicken and kale), which raised $700 million in private funding, went public, popped to $4.7 billion, and then deflated to $3.5 billion. Oddity, a firm I invested in, priced at a $2 billion valuation, ran to $2.7 billion, and closed yesterday at $1.5 billion. Better Mortgage reached a private valuation of $6 billion in the private markets before its SPAC, and now trades at a valuation of $123 million. I’m not immune. I invested in Better at a valuation of $600 million and haven’t sold a share because my SPAC is “different.”

And these IPOs are, relatively speaking, wins. But wait — isn’t the market up? Yes, but like college rankings, the indices are a weapon of mass distraction: 70% of the gains have come from just seven stocks. BTW, OpenAI is raising funds at a $90 billion valuation — a threefold increase from earlier this year. It has real revenue and explosive growth. When will it go public? A: When existing shareholders believe there is no additional upside.

WTF Happened?

Simple, really. When capital piles in returns go down, and private market investors want to capture the upside previously leaked to public investors. Charismatic promoters weaponized CNBC and social media, more hungry for entertainment than news, FOMO infected the masses, and MBS pivoted from terrorism to capitalism creating a torrent of capital to be deployed.

VC firms, who posted remarkable returns the first two decades of the millennium, needed a home with a backyard big enough to absorb billions in fresh capital. Tens of billions piled into pre-IPO growth firms. Never underestimate the market’s ability to create a product when consumers have cash in hand.

The Shift

Does this mean there’s something rotten at the heart of the capital markets? Yes, but not what it seems. The problem isn’t that IPOs have become a pump and dump scheme (often they are). The problem is that they don’t matter. The center of gravity is shifting from public to private capital. The change has been incremental, so it doesn’t get much media attention. But market trends are similar to kids: If you aren’t with them every day the changes feel implausible when you finally see them. In this case, however, Grandma would remark, “I can’t believe how much you’ve shrunk!” If the shift continues, expect an ever-greater concentration of capital and power in fewer hands, and depressed economic returns available to the “P” in IPO.

Structural Decline of the IPO

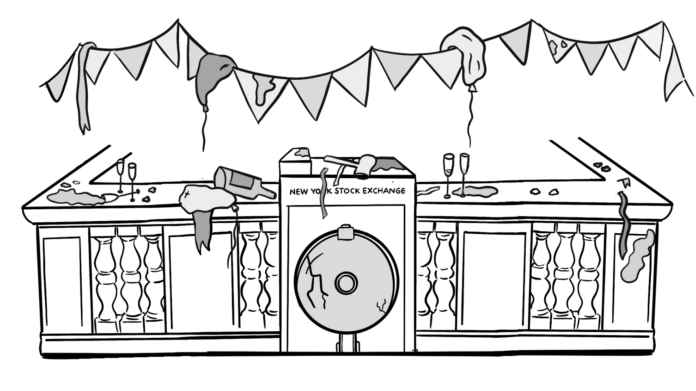

When I was a 22-year-old analyst at Morgan Stanley in the 1980s, good companies went public when they wanted to raise capital and provide liquidity to investors and employees, in that order. In 2002 I participated in the Nasdaq bell-ringing ceremony for Red Envelope, a firm I’d founded five years earlier. The feeling was, to that point, singular — I’d made it. I was at the helm of the bobsled of capitalism and would be financially secure the rest of my life. Dudes would want to be my friend, and women would want to sleep with me. Such an awesome bell. Spoiler alert: none of that happened. Maybe some new friends.

It’s been gradual, but that bell no longer rings true. The product it introduces brightens up a room by leaving it, as returns are concentrated among a few outsized winners. Companies are waiting longer to go public and issuing fewer shares with no real voting power. And many, perhaps most, of them offer little upside to their new owners.

In 1980, 9 out of 10 tech IPOs were profitable. In 2021, it was 1 in 5. Among all venture-backed companies, in 1980, 78% were profitable; in 2021, 10%. Among the 13 VC-backed companies that went public in 2022, not one was profitable.

Deepest Pockets

The rise of the unprofitable IPO isn’t a matter of companies going public earlier in their growth cycle. On the contrary, many of them are massive and raise huge amounts of capital before they go public. Just 10 years ago, when venture capitalist Aileen Lee coined the term “unicorn” to refer to a private company with a valuation over $1 billion, she was able to identify just 39 of them. Today there are 1,221.

Growth, tax avoidance, bailouts, debt-fueled spending orgies, and the weaponization of governments that pass laws to privatize gains and socialize losses have formed chunks of private wealth the size of Ayers Rock. Public capital was once the hypermatter for the jump to lightspeed, but no more. Sovereign wealth funds including ADIA and PIF, mega venture funds Softbank, Sequoia, and Andreessen Horowitz, wealthy individuals, and corporations now deploy billions where their predecessors could only write checks for millions. They have no choice but to make investments in $100 million+ chunks as you can’t put $10 billion to work $10 million at a time.

In 2007, Microsoft’s $240 million investment in Facebook at a $15 billion valuation was deemed “astronomical.” Google raised just $26 million before it went public; Netflix, $102 million. Tesla, in a capital-intensive business, raised less than $200 million in equity and another $500 million in debt before its IPO. Fast-forward to today: Six distinct VC investments of $100 million+ closed last week. Elon’s other company, SpaceX, has raised $9.4 billion across several rounds … and remains private.

Private Capture

With great wealth comes great opportunity. Historically, a company could be expected to grow long past its IPO, and the resulting share gains were available to anyone with a Schwab account and the foresight to buy in early. Google provided investors a 30% annual return for the first decade post-IPO, Facebook, 19%. If you invested $1,000 in Apple at its IPO in 1980, it would be worth $1.75 million today.

But if you don’t need the public markets for capital, why give up those gains to the unwashed masses? You don’t,unless it’s the latter stage of a pump and dump. Uber raised $10 billion in private capital, most of it from Softbank and the Kingdom, before going public in 2019 at a valuation of $82.4 billion. Four years later, public shareholders have earned a 3.5% annual return. Blue Apron raised $135 million privately before its IPO — more than Netflix and Google combined.

Companies going public today aren’t necessarily bad businesses. Airbnb is a great company, one of my largest holdings, but it’s been a far better investment for its private backers than people in the public markets — three years after its IPO, it trades below its first trade, when public-market investors could purchase stock. Private investors who don’t need the public markets to fuel growth anymore are holding on to companies longer, squeezing all the juice before tossing husks to the masses.

Table Scraps

So why go public at all? Like winemakers getting one last press from flattened grapes for their bargain label, private capital providers have one more trick up their sleeve, and it’s part of the story of the decline of the IPO.

“Initial Public Offering” is a misnomer, because rarely are shares sold initially to the public. Instead, bankers sell them to a group of buyers made up of the bank’s favored institutional customers. The first day “pop” is the difference between what those buyers pay the company (the “offering price”) for their shares, and what they can sell the shares for on the first day of trading. Access to IPO shares at the offering price is a reward to the institutional clients of investment banks who generate fees elsewhere (i.e., not you). To reward their clients and set a positive tone for the stock, the banks want a first-day pop. This isn’t new, and there’s long been tension between these banks and the companies, who see the pop as money left on the table. What’s changed is the machinations used to generate the pop and how swiftly it dissipates.

One secret is tiny floats. In 1980 the median float at IPO — that is, the percentage of the company offered to the public — was 29% of the total shares. In 2022 that number was 15%, the lowest in four decades. In an efficient market, float shouldn’t affect price, but if you can turn the hype machine up high enough and squeeze supply, you have the Lost Ark of marketing: artificial scarcity. Instacart offered only 8% of its total shares to the public when it IPO’d a few weeks ago. The story led the financial press for the day, and the stock gained 12% on its first day of trading. Airbnb offered just 7.5% of its shares to the public, and the stock more than doubled at the opening bell.

Decarceration

Historically, a short-term pop was less valuable, because insiders were subject to lockups, typically for 180 days, before they could sell their shares. However, that too is changing. In 2021, 25% of IPOs featured shorter lockup agreements that allowed insiders to sell before the 180 days were up — that share was the highest on record. Of that group, two-thirds were tech companies (shocker). Direct listings (which skip the banker-institution pipeline) are promoted as a more democratic alternative to IPOs with “open and equal access for all” and are increasing in popularity. To be clear, a direct listing has less to do with access, and more to do with dumping as there are no lockup requirements.

The other benefit of a small float is it allows insiders to retain more control. That goes hand in hand with the increase in dual-class share structures. These provisions grant insiders special shares that have 10 times the voting power. Founders love this because it allows them to decouple risk from control. In 2021, 24% of IPOs had dual-class share structures, up from 2% in 1980. Among tech companies, that number was 46%. Robinhood’s mission is to “democratize investing” — unless you invest in Robinhood, where the founders own 16% of the company but control 66% of the voting shares. The founders haven’t democratized investing, they’ve autocratized it.

Private Liquidity

The second motivation for an IPO is creating liquidity for early investors and employees. But public ownership is no longer the only way to create liquidity. Investors are increasingly able to unload some of their stock in the private markets. OpenAI is in talks to sell existing shares at a healthy valuation. eToro recently sold $120 million. And in the first half of last year, while the IPO market was frozen over, private equity firms sold $57 billion in secondary shares — a record high.

In the VIP

With no need for public-market financing, and more options for finding liquidity, private investors will continue to fund a company until the firm arrives at one of two stations: The company is strong but mature and the returns from its growth phase are fully harvested, or its model is suspect and existing shareholders need to deploy a series of false signals to greater fools so they can fling feces at tourists to the unicorn zoo.

And while private capital investors (aka the very rich) reap the gains, public investors (aka everyone else) have scant access to the markets where real wealth is created. As capital concentrates, so does power. The “shareholder class” has always been elite. But, at one time, it reached down to the merely affluent and then, through pension and retirement funds, to the masses — diffusing influence, and strengthening democracy. Public ownership’s transparency requirements are preventive against collusion, graft, and a steady march toward a dynastic society.

Instead we have bailouts of the rich, tech firms who capture trillions building a thick layer of innovation on top of public investments while decreasing R&D and paying less taxes, and an idolatry of innovators who, despite being absent fathers or just shitty investors, continue to capture our affection and capital.

What to Do?

Disavow yourself of the notion that you, or anybody else, knows how to pick stocks. Invest in low-cost ETF and index funds. Also, just because someone has chunky glasses, is on CNBC a lot, or made a lucky investment in the Amazon of China, does not mean they know what they’re doing. In fact, they may be lousy fiduciaries for your capital. Actually, that’s not accurate. They have been horrible fiduciaries for other people’s capital. Warren Buffett says the markets are a vehicle for transferring wealth from the impatient to the patient. The IPO markets are increasingly a(nother) mechanism for transferring wealth from young to old, poor to rich, and public to private.

Life is so rich,

![]()

P.S. This week on the Prof G Pod I spoke with Senator Chris Murphy. We discussed loneliness, social media, and capital vs. labor — listen here.

P.P.S. Last chance to sign up for Section’s AI for Business Mini-MBA. I’ll be kicking things off with a live lecture on Oct. 18.