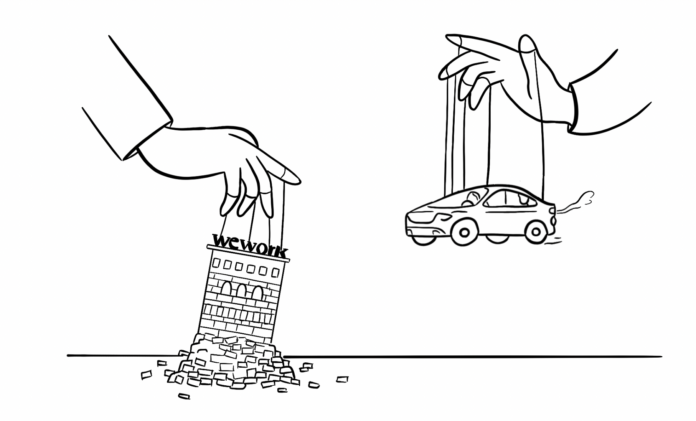

The tsunami of private capital that crashed against digital innovation after 2008 shaped a new economic entity: the unicorn. Among private companies valued at over $1 billion, the two that marked the era were Uber and WeWork. Uber was the second tech company to breach a $50 billion private market valuation (Facebook was first), and WeWork peaked at a valuation of $47 billion. Since leaving the barn, their paths have diverged: Uber is publicly traded, profitable, and valued at more than $100 billion; WeWork filed for bankruptcy this week after burning through $22 billion — on its own, lead investor Softbank immolated $14 billion, likely the largest venture loss in history.

The two businesses raised a combined $44 billion in private capital, substantially more than the total combined capital provided to birth Amazon, Apple, Facebook, Google, and Microsoft. How was Uber able to convert its massive capital hoard into a profit-generating enterprise, while WeWork set its cash on fire? I believe two fundamental factors drove these divergent outcomes: the idolatry of innovators and the power of the asset-light model.

The Dilemma’s Innovator

Founding a business that achieves any level of success requires ambition, talent, an irrational belief that “this” makes sense, and most important the ability to attract a flock of investors who consent to engage in your hallucination. The best founders are Zealots.

Zealots are high-talent, high-energy people — but they also tend to be narcissistic and divisive assholes. If you’re thinking “Takes one to know one,” trust your instincts. Zealots make good founders, but as companies mature, the ratio of their passion relative to the cost incurred by their difficult personalities erodes. Maturity calls for sober leaders who are better at managing risk and serving the market’s desire for predictable, if not remarkable, growth: Pragmatists.

Some (i.e., few) founders can make the transition, tempering the quicksilver aspects of their personality without losing their drive or vision. Watching the evolution of Bill Gates is to see a man evolve from Australopithecus afarensis to Homo sapiens in one lifetime. The wealthiest man in the world, Elon Musk, is still dragging his knuckles across the floor at his companies. An antisemite who controls an influential media business and a global communications network — what could go wrong? Prediction: The records for the most shareholder value created and lost will be set by the same person. But I digress.

Uber and WeWork had the blessing/curse to be founded by Zealots, men so irrationally committed to their vision that they ignored naysayers, business issues, laws, ethics, and math. Though, to date, a disregard for laws or morality has been a feature not a bug across the innovation economy. Math proves to be the arbiter of who survives/thrives. WeWork was the ultimate expression of a Zealot-founded company, exhibiting hypergrowth, a proliferation of side projects, and a company culture based on a cult of personality bordering on a (wait for it) cult. Founder Adam Neumann inspired devotion and elicited hard work from his team, but he created a workplace that felt more like a movie of the week than a public company. It likely could have survived this, as Uber did, but profligate spending ($60 million Gulfstream G650) and self-dealing transactions — (personally licensing the “We” brand to the company for $5.9 million) triggered the market’s gag reflex.

Neumann’s flaws were evident to insiders long before the company’s 2019 aborted IPO afforded investors a peek inside the circus tent and required the board to finally address the Neumann issue. However, it swapped in one Zealot for another — in this case business history’s greatest enabler: SoftBank’s Masayoshi Son. The Japanese billionaire was the largest backer of WeWork, having invested $6.4 billion by the time of the failed IPO, and he’d once told Neumann he needed to be “crazier.” Masa doubled down on his investment (literally, with a $9.5 billion “rescue package”) and took over the company himself.

A decent definition of “crazy” is doing the same thing while expecting a different outcome. So Son followed his own advice and became fucking insane, shoveling good money after bad. After a legal fight with Neumann, and the world’s largest blink by Masa (paying Neumann a billion for his shares), there was a SPAC, and more hemorrhaging of capital.

If WeWork was the ultimate Zealot firm, Uber was not far behind. The company employed several questionable business strategies under Travis Kalanick’s leadership, including spamming competing taxi apps with fake rides, tracking the frequency of one-night stands by city (and coining the Uber home “the ride of glory”), and generally evading (breaking) the law. Several fraud accusations, sexual harassment scandals, and a revolt by five of the company’s largest investors later, and Kalanick was forced to resign. (He also sold most of his shares to SoftBank, but Masa subsequently had to unload them to pay for his losses in other investments, including WeWork.)

WeWork enabled Neumann, even after it fired him. Uber, in contrast, belatedly demonstrated admirable corporate governance. The board kicked Kalanick out and brought in a deft Pragmatist, Dara Khosrowshahi. Dara learned his craft at the feet of Hall of Fame operator Barry Diller, then spent 12 years as CEO of Expedia honing it. Perhaps the best evidence that Khosrowshahi was the right person for the job? He turned it down. “Why would I ever jump into that mess?” was his response. (And when he told Diller he was considering it, his mentor said, “you’re fucking crazy,” and hung up on him.) After changing his mind, he led Uber through a painful but necessary changes. Four years ago the company’s Q3 loss was$1.2 billion; this year, a net profit of $221 million — its second straight profitable quarter.That will likely continue. Pragmatist.

OPA

For most of business history, having assets was good, and having more was even better. However, one of technology’s tectonic unlocks has been elevating information (bits) over objects (atoms). In the information age, owning assets is one business, while operating them is another, and each demands distinct capital structures, management approaches, and operational skills. Businesses offering the greatest return on invested capital don’t have much capital (assets) and can scale up faster, as they don’t bind themselves to cars, apartments, or even inventory. (Think: Amazon Marketplace.) Using other people’s assets makes firms more resilient, because they can scale down as inexpensively, during bad times, as they scaled up. I wrote about this in 2020, reflecting on the lessons of the pandemic:

Uber rents space in other people’s cars, driven by non-employees (in the eyes of the law, anyway). The second an Uber car stops making the company a profit, the asset and labor disappears and costs the company nearly nothing. Revenue can go to zero in a crisis, and Uber can reduce costs 60%–80%. Hertz, on the other hand, owns its cars and went bankrupt. Boeing has $10 billion in cash, but if its revenue goes down 80%, they can take costs down maybe 10%, maybe 20%.

When WeWork filed its ill-fated IPO prospectus in 2019, one of the many frightening pieces of information was its lease commitments. While WeWork did not own the buildings it operated, it entered into long-term lease contracts with landlords, which is the next best/worst thing to ownership. This gave WeWork sole use of/responsibility for that real estate — functionally similar to buying the property with long-term financing. As of its attempted IPO, WeWork was contractually obligated to pay $47.2 billion in lease payments over the next 15 years. That’s enough to build 31 Burj Khalifas from the ground up.

![]()

Fast forward to 2023, and those lease obligations have pushed WeWork into bankruptcy. On September 6 the CEO acknowledged they were “two-thirds of total operating expenses … and are dramatically out of step with current market conditions” and announced plans to renegotiate them. The “We know we’re contractually obligated to pay but would rather pay less” conversation didn’t go well. Uber, in contrast, has been able to navigate the departure of its CEO and rising and falling competition, and has made strategic bets of varying success in food, logistics, and other related businesses, because of the flexibility of its asset-light model. WeWork has only one means of survival: Rent more desks. It couldn’t, so it didn’t.

Not Dead Yet

Bankruptcy, one of capitalism’s best features, is handcrafted for a firm whose main problem is … lease commitments. One path forward for WeWork would be to use bankruptcy to look over its office portfolio, get out of the leases of underperforming locations, and get better deals on the good ones. It ought to have some leverage: The commercial office market has been a shitshow since the pandemic, with values down 25% year to date, after losing 38% last year. Office property values are expected to be 40% lower by 2029 than they were in 2019. Think about this. It’s likely U.S. commercial office space has shed more gross value than any asset class, globally. A Sophie’s Choice of “cut this rate in half or we walk” may be an offer your average landlord can’t refuse.

But there may be a better way. Go asset-light and ask someone else to own that space. Hotel brands figured this out decades ago, and there’s nothing WeWork resembles more than a hotel. They are both REaaS, to borrow an acronym from tech, Real Estate as a Service. Here’s how the Four Seasons and the Ritz do it: They run their hotels through operating contracts with the building owners, earning them fees and a share of top-line revenue. It’s the “one weird trick” that converts a business weighed down by expensive, illiquid real estate into a 21st century asset-light operation. Another approach would be to franchise the business — which is what WeWork version 2 (the era after firing Neumann and before Chapter 11) did with its international operations. The franchisees have to sort out their real estate risk and strategy, but they have the benefit of local expertise. (The extreme asset-light option would be to go full Uber, though the better analogy is Airbnb: Convert the business into a network of providers who bring their own office spaces to rent. But that’s neither the promise nor product that WeWork offers, and it’s likely fraught with security risks and operational challenges.)

Both WeWork and Uber have an asset that is worth billions, brands that have reached Elysium — they are the generic term for their category. WeWork’s brand has been dinged by the business failures of the past few years, but the impact of corporate missteps on consumer brands is typically muted. Airlines, for example, can’t stay out of bankruptcy court (American, Delta, and United all being recent examples), but their brands keep flying. I expect more than a few potential buyers are fielding brand equity surveys right now, gauging the strength of WeWork’s potentially most valuable asset. My bet is Barry Sternlicht brings the firm out of bankruptcy. We’ll see.

All of this assumes there’s a market for what WeWork is selling. There is. Three in four workers would take a “flexible work environment” over better pay. But for most people under 40, the kitchen table or local Starbucks (another brand that could get into this space?) isn’t going to cut it. And a WeWork contract is more attractive than a lease to an employer looking to go asset-light. The service aspect of short-term and small-lot rentals is the office space business of the future. The asset base is an albatross.

Home Game

In the C-Suite, the Zealot and Pragmatist personality types are sequential re a firm’s evolution. In relationships, the two mix well. I’ve been going through pictures from a backpacking trip I took through Europe with my friend Lee 35 years ago. He brought maps, a wallet belt, and traveler’s checks. On the train, he’d plan out our day, and I would comb the train and try to find new friends (i.e., women) we could hang out with at our destination. Lee and I shared the same doctor (Raul Zimmerman), who summarized our relationship when he heard we were headed to Europe: “Lee will make sure you don’t miss too many trains, and Scott will make sure you miss a few.” Lee and his husband came to watch me on Bill Maher a couple weeks ago, and Lee pulled me aside afterward and said, “I’m just so proud of you and what you’ve accomplished.” This was so meaningful for me. I think of myself as a fairly fearless person, but I’ve never had the confidence to say this to a male friend. Still time. Anyway, we’ve been making and missing trains for four decades. So blessed.

Life is so rich,

![]()

P.S. No Mercy / No Malice is offering exclusive sponsorships of our newsletter and site. More here.

P.P.S. Want to know what it takes to build a generative AI bot? Section CEO Greg Shove is lecturing on Nov. 29 on how Section built its new AI course tutor. Sign up here.