AI could improve your life by removing bottlenecks between what you want and what you get

By Bruce Schneier, Harvard Kennedy School

Artificial intelligence is poised to upend much of society, removing human limitations inherent in many systems. One such limitation is information and logistical bottlenecks in decision-making.

Traditionally, people have been forced to reduce complex choices to a small handful of options that don’t do justice to their true desires. Artificial intelligence has the potential to remove that limitation. And it has the potential to drastically change how democracy functions.

AI researcher Tantum Collins and I, a public-interest technology scholar, call this AI overcoming “lossy bottlenecks.” Lossy is a term from information theory that refers to imperfect communications channels – that is, channels that lose information.

Multiple-choice practicality

Imagine your next sit-down dinner and being able to have a long conversation with a chef about your meal. You could end up with a bespoke dinner based on your desires, the chef’s abilities and the available ingredients. This is possible if you are cooking at home or hosted by accommodating friends.

But it is infeasible at your average restaurant: The limitations of the kitchen, the way supplies have to be ordered and the realities of restaurant cooking make this kind of rich interaction between diner and chef impossible. You get a menu of a few dozen standardized options, with the possibility of some modifications around the edges.

That’s a lossy bottleneck. Your wants and desires are rich and multifaceted. The array of culinary outcomes are equally rich and multifaceted. But there’s no scalable way to connect the two. People are forced to use multiple-choice systems like menus to simplify decision-making, and they lose so much information in the process.

People are so used to these bottlenecks that we don’t even notice them. And when we do, we tend to assume they are the inevitable cost of scale and efficiency. And they are. Or, at least, they were.

The possibilities

Artificial intelligence has the potential to overcome this limitation. By storing rich representations of people’s preferences and histories on the demand side, along with equally rich representations of capabilities, costs and creative possibilities on the supply side, AI systems enable complex customization at scale and low cost. Imagine walking into a restaurant and knowing that the kitchen has already started work on a meal optimized for your tastes, or being presented with a personalized list of choices.

There have been some early attempts at this. People have used ChatGPT to design meals based on dietary restrictions and what they have in the fridge. It’s still early days for these technologies, but once they get working, the possibilities are nearly endless. Lossy bottlenecks are everywhere.

Take labor markets. Employers look to grades, diplomas and certifications to gauge candidates’ suitability for roles. These are a very coarse representation of a job candidate’s abilities. An AI system with access to, for example, a student’s coursework, exams and teacher feedback as well as detailed information about possible jobs could provide much richer assessments of which employment matches do and don’t make sense.

Or apparel. People with money for tailors and time for fittings can get clothes made from scratch, but most of us are limited to mass-produced options. AI could hugely reduce the costs of customization by learning your style, taking measurements based on photos, generating designs that match your taste and using available materials. It would then convert your selections into a series of production instructions and place an order to an AI-enabled robotic production line.

Or software. Today’s computer programs typically use one-size-fits-all interfaces, with only minor room for modification, but individuals have widely varying needs and working styles. AI systems that observe each user’s interaction styles and know what that person wants out of a given piece of software could take this personalization far deeper, completely redesigning interfaces to suit individual needs.

Removing democracy’s bottleneck

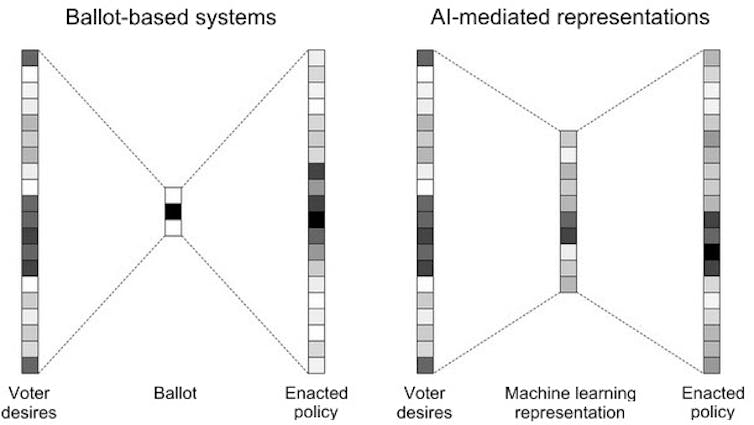

These examples are all transformative, but the lossy bottleneck that has the largest effect on society is in politics. It’s the same problem as the restaurant. As a complicated citizen, your policy positions are probably nuanced, trading off between different options and their effects. You care about some issues more than others and some implementations more than others.

If you had the knowledge and time, you could engage in the deliberative process and help create better laws than exist today. But you don’t. And, anyway, society can’t hold policy debates involving hundreds of millions of people. So you go to the ballot box and choose between two – or if you are lucky, four or five – individual representatives or political parties.

Imagine a system where AI removes this lossy bottleneck. Instead of trying to cram your preferences to fit into the available options, imagine conveying your political preferences in detail to an AI system that would directly advocate for specific policies on your behalf. This could revolutionize democracy.

One way is by enhancing voter representation. By capturing the nuances of each individual’s political preferences in a way that traditional voting systems can’t, this system could lead to policies that better reflect the desires of the electorate. For example, you could have an AI device in your pocket – your future phone, for instance – that knows your views and wishes and continually votes in your name on an otherwise overwhelming number of issues large and small.

Combined with AI systems that personalize political education, it could encourage more people to participate in the democratic process and increase political engagement. And it could eliminate the problems stemming from elected representatives who reflect only the views of the majority that elected them – and sometimes not even them.

On the other hand, the privacy concerns resulting from allowing an AI such intimate access to personal data are considerable. And it’s important to avoid the pitfall of just allowing the AIs to figure out what to do: Human deliberation is crucial to a functioning democracy.

Also, there is no clear transition path from the representative democracies of today to these AI-enhanced direct democracies of tomorrow. And, of course, this is still science fiction.

First steps

These technologies are likely to be used first in other, less politically charged, domains. Recommendation systems for digital media have steadily reduced their reliance on traditional intermediaries. Radio stations are like menu items: Regardless of how nuanced your taste in music is, you have to pick from a handful of options. Early digital platforms were only a little better: “This person likes jazz, so we’ll suggest more jazz.”

Today’s streaming platforms use listener histories and a broad set of features describing each track to provide each user with personalized music recommendations. Similar systems suggest academic papers with far greater granularity than a subscription to a given journal, and movies based on more nuanced analysis than simply deferring to genres.

A world without artificial bottlenecks comes with risks – loss of jobs in the bottlenecks, for example – but it also has the potential to free people from the straightjackets that have long constrained large-scale human decision-making. In some cases – restaurants, for example – the impact on most people might be minor. But in others, like politics and hiring, the effects could be profound.![]()

Bruce Schneier, Adjunct Lecturer in Public Policy, Harvard Kennedy School

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.