What can we learn from the history of pre-war Germany to the atmosphere today in the U.S.?

By David Dyzenhaus, University of Toronto

The Guardian recently published an interview with U.S. Sen. Bernie Sanders about what happens if Donald Trump wins this year’s presidential election in the United States.

His dire answer: “It will be the end of democracy.”

The challenge the U.S. faces, Sanders said, “is to be able to show people that government in a democratic society can address their very serious needs. If we do that, we defeat Trump. If we do not, then we are the Weimar Republic of the early 1930s.”

Sanders is of course evoking the extreme political polarization and social discontent of the last three years of Germany’s first experiment with democracy.

That experiment ended with Adolf Hitler’s seizure of power in 1933.

The senator is right that there are frightening echoes of the end game of Weimar in western democracies. But in the U.S., at least, his timing is off. The United States already is the Weimar Republic of the early 1930s.

Polarization in pre-war Germany

Naturally, there are some differences.

In Germany, the main fault line of polarization was between the far-right factions, with the Nazi Party the most prominent, and the Communist Party — both of which contested elections with the express intention of destroying democracy if they won power. In contrast, the main division in the U.S. is between Democrats and the far-right groups that dominate Trump’s Republican party.

My expertise is not political science but law, in particular the rule of law. I study the nature of law and its relationship to politics.

I wrote a book about the problems of the legal and political order in pre-Hitler Germany — and why those circumstances remain highly relevant to contemporary debates about what’s going on in the United States and other western democracies (including debates in Canada).

The Weimar Constitution had existed for only 14 years when Hitler forced the German parliament to make his will the ultimate source of legal authority.

His path to power was facilitated by the ease with which Article 48 of the constitution — the emergency powers provision that allowed the president to bypass parliament — could be exploited.

The resilience of the U.S. Constitution

In contrast, the U.S. Constitution dates from 1789, which makes it the most established constitution of the oldest democracy. It showed its resilience on Jan. 6, 2021, in the failed attempt by Trump and his supporters to take power by insurrection after he lost the 2020 election to Joe Biden.

Konrad Adenauer, West Germany’s first president who was elected after the Second World War, later reflected that the problem with Weimar was not its constitution, but that there weren’t enough democrats — meaning politicians, judges, lawyers and others who believed in democracy.

Three years ago in the United States, only a small number of small-d democrats stood between a successful coup and Biden taking office: the Republican-appointed judges who rejected Trump’s attempts in the courts to contest particular elections, the Republican election officials who withstood the pressure to rig the votes in their districts and even Vice-President Mike Pence, though it seems that he wavered dangerously until the last minute.

Weimar democracy was similarly salvageable until the end of 1932, and so the analogy between it and the U.S. in early 2024 is strong.

The role of lawyers and courts in such scenarios can be crucial.

Coup d’etat in Prussia paved the way

In 1932, the German federal government — dominated by right-wing aristocrats — used the emergency powers provision of the Weimar constitution to replace the legal state government of Prussia, one of 39 separate states that made up the German republic. This coup d’état effectively took over the powers of a state that was the main bastion of democratic resistance to the extreme right-wing forces of the time.

At the time of the coup, the Prussian state government considered armed resistance. But because it felt such action would end in defeat and, as social democrats, they were committed to legality, they chose to challenge the constitutional validity of the decree before the Staatsgerichtshof — the court set up by the Weimar Constitution to resolve constitutional disputes between the federal government and the states in Germany’s federation.

After hearing oral arguments between Oct. 10-17, 1932, the court fudged its decision in a way that effectively upheld the decree in a judgment on Oct. 25.

This decision is regarded as a significant precursor to Hitler’s seizure of power in 1933 and his decision to make himself the ultimate source of legal authority in Germany, thus effectively putting him beyond the reach of the law.

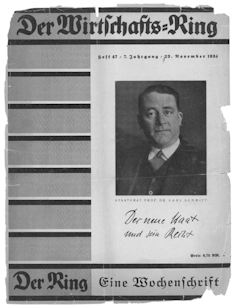

Some of the most prominent legal scholars of the time appeared on both sides of the dispute, including Carl Schmitt, a fascist legal theorist who presented the federal government’s side in the Prussia case and then signed up with the Nazis after 1933.

Nazi lawyer still admired

Schmitt was determined throughout his career to use legal arguments to destroy liberal democracy from within. Today, Schmitt is very popular — along with other right-wing figures from the Weimar period — with the far-right coterie of lawyers who tried to mastermind Trump’s own attempt at a coup in January 2021.

The U.S. Supreme Court will soon decide current and potential future cases involving Trump’s challenges to the rule of law. For example, Trump has mused that if he is re-elected, he could use the Insurrection Act to suppress any political protests.

The Supreme Court’s decisions on cases involving Trump’s legal authority could be as momentous for the future of democracy in the United States as the decision of Staatsgerichtshof in 1932.

With a majority of conservative judges on the U.S. Supreme Court — including Justice Clarence Thomas, whose wife has been accused of trying to help Trump overturn his election defeat — the portents for democracy and the rule of law are not good.![]()

David Dyzenhaus, Professor of Law and Philosophy, University of Toronto

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.