Middle East crisis: US airstrikes against Iran-backed armed groups explained

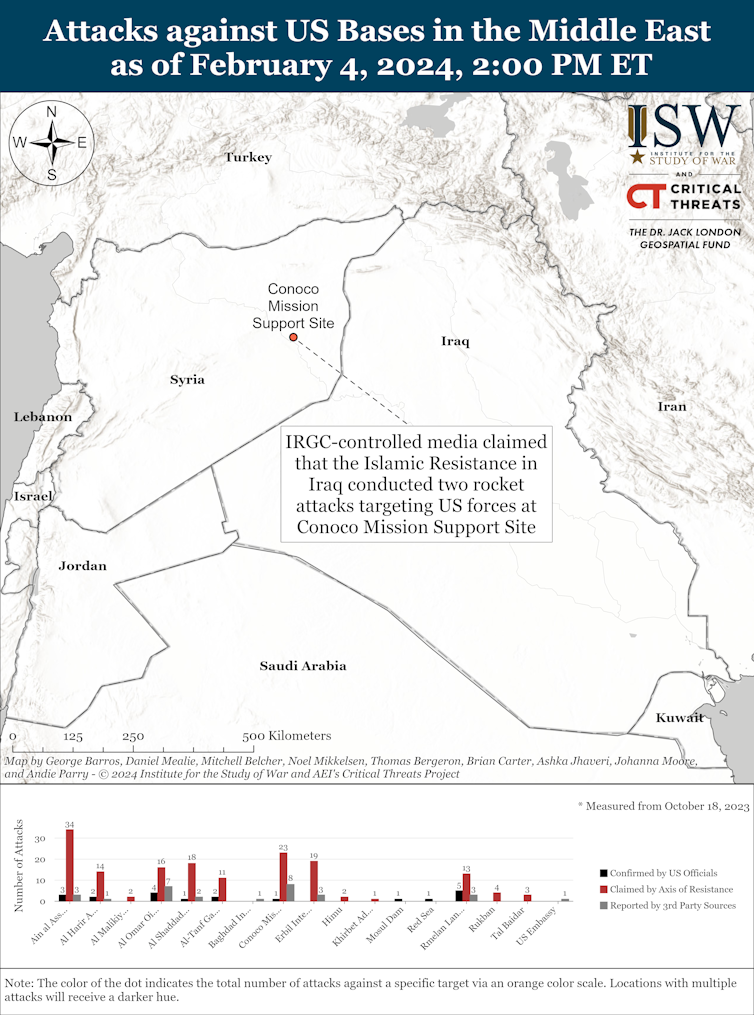

US airstrikes on Iran-backed armed groups on February 2 have been anticipated for some time. Since the Hamas attacks in Israel on October 7, US forces in the Middle East have been targeted more than 150 times. These attacks, mainly on US bases in Iraq and Syria caused minimal damage thanks to US air defence capabilities.

The Biden administration had responded with modest strikes on the militias’ weapons storage and training sites. But a drone attack on January 28 on Tower 22, a US base on the Jordanian-Syrian border, killed three soldiers and wounded dozens of others.

The deaths represented an unofficial red line for many in Washington, and political pressure mounted fast on President Biden to respond more forcefully against the armed groups – or even against Iran itself.

Officials said the air strikes targeted command-and-control sites, intelligence centres and drone storage facilities in Iraq and Syria affiliated with the militias and also with the Quds Force, a branch of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps.

Biden also stated that the US would continue strikes at times and places of their choosing.

Though more widespread than previous strikes, the response was carefully calibrated to avoid stoking a broader war. Furthermore, the US signalled its intentions days in advance, giving the groups and their advisers time to move to minimise casualties.

Militant groups targeted

There are about 40 militant groups in the region backed by Iran. These include high-profile groups such as Hamas, which carried out the October 7 attack in Israel as well as Hezbollah, which has been engaged in cross-border fire with Israel on the Lebanon border since October. Meanwhile, Houthi rebels in Yemen have faced separate US and UK strikes in response to their targeting of commercial ships in the Red Sea.

But many other, smaller groups operate as well. Responsibility for the lethal drone strike was claimed by the Islamic Resistance of Iraq, a loose network of Iran-backed militias including Kataib Hezbollah, which fought against coalition forces during the Iraq war. These and other militias have continued to target US troops who remain in the region to prevent the resurgence of Islamic State.

Iran provides a mix of training, intelligence, funding and weapons to groups within its self-described “axis of resistance”. But Tehran does not fully control the militias, who operate with varying degrees of autonomy, and who might be better seen as affiliates than proxies.

US political choices

The Biden administration has been walking a tightrope in the Middle East. On the one hand, the administration’s primary aim for the past four months has been preventing a regional war in the aftermath of the Hamas attack and the subsequent war in Gaza. At the same time, the US has sought to deter adversaries who have been using increasing degrees of armed force against US personnel (and, in the case of the Red Sea, against international commercial vessels).

The challenge has been in determining a response that is forceful enough to deter further attacks, but not so devastating as to provoke a fully fledged war.

With the election year, Biden is also facing additional scrutiny from home on his foreign policy decisions. Donald Trump has long sought to make Biden look weak on Iran, while many Democrats have been critical of the president’s use of airstrikes, as well as his approach to the war in Gaza. The calibrated airstrikes of the weekend will probably attract further criticism from both sides – for going too far or not far enough.

Gaza conflict

There’s no guarantee that a ceasefire (temporary or permanent) would bring a stop to attacks on US troops in Iraq and Syria, or to Houthi attacks on vessels in the Red Sea. But it’s undeniable that the crisis in Gaza has emboldened armed groups around the region, who have repeatedly used the war to justify their actions.

The US, Egypt and Qatar have been mediating between Israel and Hamas to negotiate a deal that would see a halt of military operations in Gaza in return for a phased release of hostages. While clearly crucial for the hostages and their families and for the civilian population of Gaza, the deal could also be the key to defusing other tensions in the region, at least temporarily.

While the deal is far from a final agreement, the nature of the US strikes was probably calibrated in part to avoid disrupting the process.

Preventing regional war

Iran, as well as Iraq and Syria, have denounced the strikes, and accused the US of aggression. But Iran has not indicated it plans to retaliate. This suggests that Tehran – like Washington – is still keen to avoid a head-to-head conflict with the US.

Meanwhile, while Kataib Hezbollah has announced it will halt attacks on US troops, other armed groups have said that this is not the end, and they will continue to strike against the US presence in the region.

For the Biden administration, the aim of preventing a regional war is still the right objective, even – perhaps especially – in the face of rising tensions. A policy of careful calibration, coupled with meaningful negotiations to halt the war in Gaza, may not be as politically enticing as flexing US military might – but it’s the approach that is most in line with the longer-term interests of the US and the region.![]()

Julie M Norman, Senior Associate Fellow on the Middle East at RUSI; Associate Professor in Politics & International Relations; Deputy Director of the Centre on US Politics, UCL

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.