A two-state solution for Israelis and Palestinians might actually be closer than ever

By Benjamin Case, Arizona State University

As the war in the Gaza Strip enters its fourth month, on the surface it might seem like possibilities for long-term, peaceful solutions are impossible. Even before the Oct. 7, 2023, attack on southern Israel by Hamas-led forces from Gaza, many analysts were already declaring the idea of a two-state solution dead.

There are real barriers to the creation of a Palestinian state alongside a separate Israel. For example, the current Israeli government rejects the creation of a Palestinian state, and Hamas refuses to recognize Israel. After Oct. 7, some analysts think the barriers are even more insurmountable.

As a scholar of political violence and conflict, I think the unprecedented scale of violence in Israel and Gaza is creating equally unprecedented urgency to find a solution, not just to the current violence, but to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Few, if any, historical conflicts neatly compare to the one between Israelis and Palestinians. But there are similarities in the fall of apartheid in South Africa in the early 1990s, when growing international pressure and an intensifying war focused attention on an unsustainable system – and pushed people to find possibilities for peace that previously seemed impossible.

The fall of South African apartheid

In 1948, the white-nationalist Afrikaner National Party was elected to run South Africa, a country that had already been controlled by a colonial white minority government.

The National Party formalized racial segregation policies in a system known as apartheid, an Afrikaans word that means “apartness” or “separateness.” Apartheid ranked people by racial group, with white people at the top, Asian and people of mixed heritage lower, and Black people at the bottom with the most restrictions and fewest rights – for example, to live or work where they chose.

Apartheid resulted in deep poverty and indignity for Black communities, quickly generating anti-apartheid social movements that South African police tried to violently suppress.

The collapse of apartheid policies in the early 1990s is often attributed to a combination of South African resistance and the economic pressure brought by international anti-apartheid boycotts of South Africa.

There was another major factor, though: South Africa’s “border war” in Namibia and Angola.

Since 1948, South Africa had imposed its apartheid policies over a neighboring region it occupied after World War II, then called South-West Africa, which is now Namibia.

Like Black South Africans, people in South-West Africa resisted apartheid. Beginning in the 1960s, South Africa’s military began employing local militias in South-West Africa to combat a Namibian independence movement. Soon after, South Africa attempted to expand its control over neighboring Angola, which was in civil war after winning independence from Portugal.

The war in South West Africa and Angola became a proxy for the ongoing Cold War and Western countries’ fear of communism spreading. The U.S. supported South Africa’s army and pro-Western militias, while the Soviet Union and Cuba supported pro-independence fighters. Cuba would eventually send 30,000 troops to fight on the ground on Angola’s side.

By the 1980s, the conflict was escalating into wider war, threatening to pull the United States and Soviet Union into direct conflict.

South Africa was forced to mobilize its reserve troops, and white South Africans began protesting at home. It was becoming clear that not just the war but the country’s brutal apartheid system was not sustainable, lending credibility to those who wanted a democratic solution.

The mutually destructive war had no clear end or military solution. South Africa and opposing armies were also running out of money to keep fighting.

This stalemate pushed Cuba, Angola and South Africa to a peace deal in 1988, and South Africa withdrew its forces.

The war with Namibia continued, but not for long.

South African Prime Minister P.W. Botha resigned in 1989 after losing the support of his own far-right party for his failure in the war and inability to impose order. In 1990, Namibia declared independence.

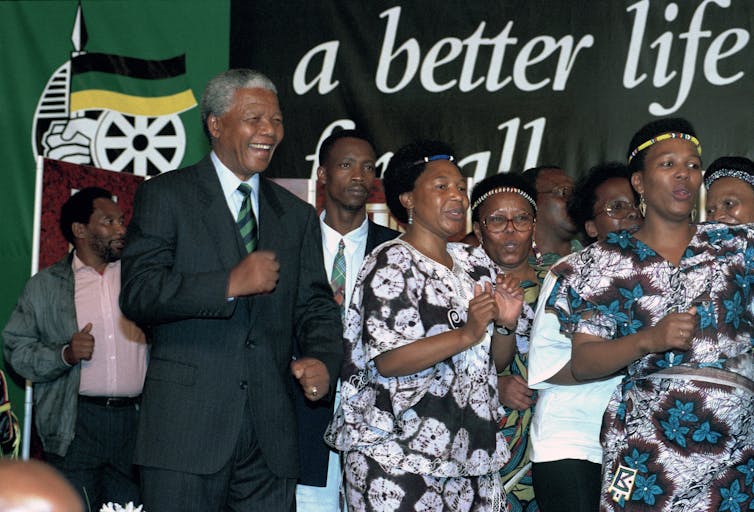

That same year, the new South African government began rolling back apartheid policies, paving the way for historic elections in 1994 that were won in a landslide by anti-apartheid leader Nelson Mandela.

South Africa’s involvement in its border war is different in many ways from Israel’s military campaign in Gaza. But there are also similarities that may offer guidance.

A way toward two states?

For more than half a century, Israel has controlled the borders of the West Bank and Gaza. Home to 5 million Palestinians, these areas exist in a kind of netherworld between being part of Israel and being separate, sovereign entities. Israel controls their territory, but Palestinians who live in the West Bank and Gaza cannot vote in Israel and do not have basic rights or freedom of movement.

It is a situation that many analysts have long understood is unsustainable, as it has repeatedly given way to extreme fighting between Israelis and Palestinians. Yet with the U.S. and other powers firmly backing Israel as a strategic ally, few could see realistic possibilities for change.

The shocking scale of violence in the war is changing that. About 1,200 people were killed and 240 were kidnapped in Hamas’ Oct. 7 attack. In Gaza, Israel’s war has killed more than 27,000 residents, mostly civilians.

I think that this violence, along with the threat of a wider war breaking out, is upending the once-remote idea of significant change in the region.

Nearly the entire population of 2 million people in Gaza have been displaced from their homes and face dire humanitarian emergencies due to food, water and power shortages, foreign aid blockages and the destruction of Gaza’s hospitals.

With Houthi militants in Yemen entering the conflict and threats from Hezbollah militants in Lebanon, the U.S. is wary of being pulled into another war in the Middle East.

Pressure is growing internationally for a cease-fire – and a two-state solution.

The U.S., the European Union and China all voice support for a two-state solution, and Saudi Arabia has made the possibility of a historic accord with Israel contingent on it.

United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres has said that a two-state solution is the “only path” to peace.

Pressure is mounting in Israel as well, as people continue to protest for the Israeli government to make a deal and bring 130 hostages still captive home alive.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s approval ratings are tanking. Israel’s economy is shrinking. And the Israeli government is increasingly divided over the war effort, with Netanyahu losing support in his own far-right party.

There remain large obstacles to realizing a two-state solution. There is also growing international consensus that a two-state solution is the only acceptable outcome of the current violence.

In my view, the conditions unfolding in Israel and Gaza are beginning to reach a breaking point, similar to the conditions in South Africa that formed prior to apartheid’s defeat.![]()

Benjamin Case, Postdoctoral research scholar at the Center for Work and Democracy, Arizona State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.