Climate change is speeding up in Antarctica

By Sergi González Herrero, Universitat de Barcelona

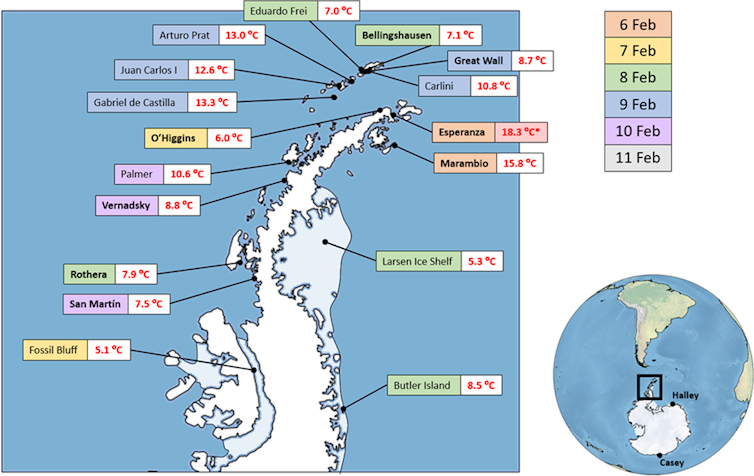

In recent years, Antarctica has experienced a series of unprecedented heatwaves. On 6 February 2020, temperatures of 18.3C were recorded, the highest ever seen on the continent, beating the previous record of 17.5C which had only been set a few years earlier.

Around February 2022, another strong heatwave in Antarctica led to record-breaking surface ice melt. In March of the same year, East Antarctica saw its strongest ever heatwave, with temperatures soaring to 30C or 40C higher than the average in some areas.

Over the last year, we have seen the lowest levels of Antarctic sea ice coverage since records began.

Events in recent years have bordered on the unbelievable, and it is difficult not to link them to climate change. In fact, studies have already emerged that clearly attribute some of these heatwaves to global warming: one of our investigations strongly suggests that without the influence of climate change, 2020’s record-breaking temperatures would not have occurred.

Antarctica’s changing climate

In 2009, a study quantified the speed of ecosystem migration due to climate change on a global scale, and documented, essentially, the speed at which certain species have to move to ensure their survival. It concluded that biomes were moving at a speed between 0.8 and 12.6km per decade, with an average speed of 4.2km per decade.

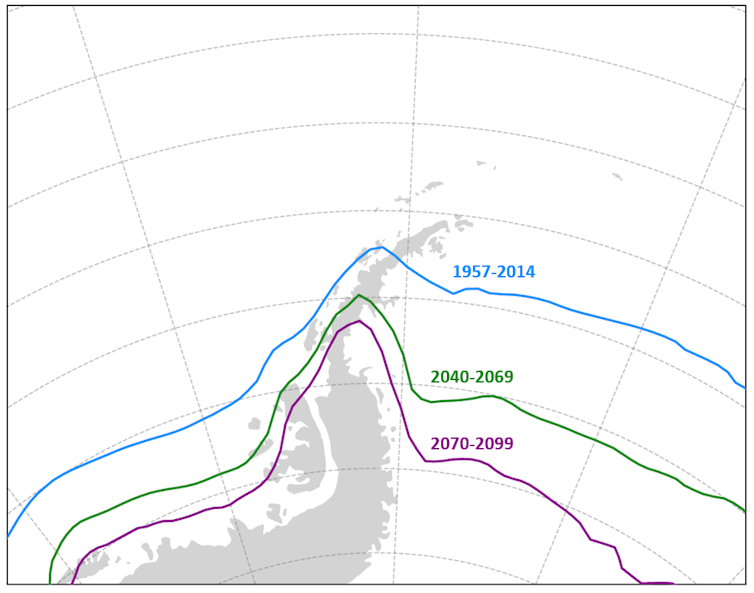

In our more recent study, published in February 2024, we adapted this measurement of speed and applied it to the edges of Antarctica. To do this, we tracked the southward migration of the zero-degree isotherm.

The zero-degree isotherm is an imaginary line that encloses the areas that are at zero degrees or lower. Its southward movement means that the area with temperatures below zero Celsius in Antarctica is getting smaller and smaller. Given that water freezes at zero degrees, this movement will have serious consequences for ecosystems and for the cryosphere (areas of the Earth where water is frozen).

Our calculations show that the zero-degree isotherm has moved at a speed of 15.8km per decade since 1957 in the area surrounding the Antarctic, while on the Antarctic peninsula itself it has moved at 23.9km per decade. As a result, it now sits over 100km south of where it was in the mid 20th century.

These measurements show that the speed of climate change on the edge of Antarctica is four times faster than the average of other ecosystems.

The effects of emissions

To predict the consequences of the southward migration of the zero-degree isotherm, we ran our data through twenty different climate models. Although there is some variation in the shift of the isotherm among the models, all agree that it will move significantly further southward over the next few decades.

The models also predict that, over the coming decades, the isotherm’s movement will accelerate regardless of emissions. However, the extent of its southward movement in the second half of the 21st century will depend on how much carbon we emit.

If we continue at our current rate of emissions, the zero-degree isotherm will continue to advance at a similar rate before slowing down during the second half of the 21st century. However, if emissions are higher, the isotherm’s migration will accelerate continuing its southward movement until the end of the century.

Impacts on the cryoshpere and ecosystems

The zero-degree isotherm’s southward movement will not remain solely in the atmosphere, it will also affect the cryosphere (all of the frozen areas of Antarctica) and the biosphere (the species that live there).

Changes in the isotherm’s position will mean more liquid rain instead of snow in the outermost regions of the continent, though it may in fact cause increased snowfall in other areas.

Reduced snowfall on the frozen sea – which acts as insulation – may lead to accelerated loss of sea ice during summer thaw periods.

Although the effects on permafrost, ice shelves and continental ice are still uncertain, it will undoubtedly affect the peripheral glaciers of the Antarctic Peninsula. These constitute one of the largest potential sources of sea level rise in the coming decades.

Changes in the cryosphere will also lead to changes in ecosystems. New areas will become habitable thanks to thawing ice, but with more areas above zero degrees, invasive species from warmer, more hospitable continents may be able to settle, and they will compete with native species for resources.![]()

Sergi González Herrero, Científico atmosférico, Universitat de Barcelona

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.