An Israeli attack on Iran’s nuclear weapons programme is unlikely – here’s why

Israel’s prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, has vowed to retaliate against Iran for the unprecedented aerial assault on April 13. He has made it clear that “we will make our own decisions, and the state of Israel will do all that is needed to defend itself”.

Iran’s attack involved around 170 drones, over 30 cruise missiles and more than 120 ballistic missiles, all directed against Israel and the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights. The attack was launched in retaliation for Israel’s April 1 strike against the Iranian embassy in Damascus, Syria, which killed two top military leaders of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC).

The timing, scale and nature of Israel’s response remain to be seen. But various options have been canvassed, including a strike of some sort against Iran’s nuclear weapons programme.

Israel has targeted Iran’s nuclear programme before. It has assassinated a number of nuclear scientists over the years, and launched a number of attacks on the country’s nuclear facilities. Physical attacks have taken the form of drone strikes and commando raids, including one in January 2018 on a facility in Tehran, in which Mossad agents stole large numbers of classified documents which Netanyahu said proved Iran was pursuing a nuclear weapons programme.

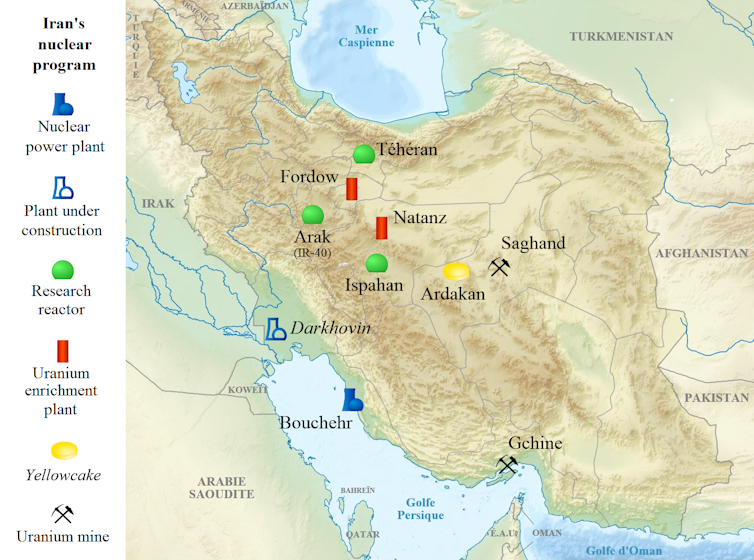

In April 2021, Iran accused Israel of orchestrating an explosion at its primary uranium enrichment facility in Natanz, resulting in substantial damage to its centrifuges. This marked the second incident within a year involving a mysterious explosion at the site. Israel has neither confirmed nor denied its involvement in either attack.

Israel is also thought to have mounted a number of cyberattacks on Iran’s nuclear programme, most prominently in June 2010 with the introduction of Stuxnet computer malware into Iranian nuclear facilities. Believed to have been created through collaboration between US and Israeli intelligence, the Stuxnet malware was designed to severely disrupt centrifuge operations at Natanz and is thought to have set back Iran’s nuclear weapons programme by years.

Iran’s nuclear weapons history

The status of Iran’s nuclear weapons programme remains unclear. The country developed a civil nuclear programme under the late Shah, and in 1970 ratified the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty, committing the country not to possess nor develop nuclear weapons.

But in the late 1980s, Iran initiated a clandestine uranium enrichment programme, acquiring essential equipment and materials from Pakistan and China. During the late 1990s and early 2000s, Iran pursued a secret nuclear weapons development project, known as the Amad Plan.

Work on this plan was thought to have halted in 2003, following the US invasion of Iraq. But it is thought that by then, Iran had the capacility to build a small and fairly crude nuclear device.

A great deal of what we know about the development of Iran’s nuclear weapons programme stems from the 2018 Mossad raid. This revealed that work on weapons development was not entirely halted, and that Iran continued to work on improving its nuclear weapons capability.

The US has responded over the years by applying increasingly severe sanctions designed to deter Iran from continuing its programme. At the same time, backchannel negotiations continued, resulting in the joint comprehensive plan of action (JCPOA) signed by Iran and the P5+1 (the five permanent members of the UN security council – China, France, Russia, the US and UK – plus Germany).

In return for sanctions relief, Iran agreed to reduce its uranium enrichment programme to a level insufficient for building nuclear warheads. It was restricted to enriching uranium up to 3.67%, a level adequate for civilian nuclear energy and scientific research, and all facilities were subject to inspection by the International Atomic Energy agency. The restrictions would be in place for 15 years.

In May 2018, the Trump administration abandoned the JCPOA. Iran responded by re-energising its weapons programme. According to a research briefing held in the House of Commons Library, the country is now thought to have exceeded the agreed limit for its uranium stockpile by a factor of 18 times, and has elevated its enrichment operations to 60%.

It has resumed operations at nuclear facilities previously prohibited under the terms of the agreement and, since February 2021, has prevented the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) from effectively monitoring its nuclear sites.

Can an Iranian ‘bomb’ be prevented?

According to a report by the Arms Control Association in Washington, Iran’s nuclear programme is now too advanced and widely distributed to be effectively nullified by military action. There are several reasons for this.

First, Iran possesses the requisite expertise to develop nuclear weapons, which cannot be eradicated through bombing raids. While targeting Iranian facilities would temporarily hinder the programme, any setbacks would likely be short-lived.

Destroying Iran’s nuclear facilities in Natanz would be essential, but accessing these facilities would necessitate a significant number of airstrikes penetrating deep into Iranian territory, while circumventing or overpowering its air defence systems.

In recent years, Iran has fortified its Natanz facility, building deep tunnels to prevent airborne attack. Even if this facility was damaged, it is thought that Iran would be capable of reconstituting it quickly – especially as various elements, including the uranium centrifuges, may already have been moved to unknown sites.

So, an effort to destroy Iran’s nuclear programme would require a large-scale military assault. This would certainly prompt a military response from Tehran, and is likely to further persuade the Islamic Republic of the necessity of accelerating its efforts to acquire its own mature nuclear deterrent.

In such a scenario, Iran might also opt to withdraw from the nuclear non-proliferation treaty, eliminating any obligation for inspections by the IAEA.

For all these reasons, the former Israeli prime minister Ehud Olmert – a regular critic of Netanyahu – said recently: “Israel can do a lot to damage Iran’s infrastructure, but Israel has no means to be able to destroy the nuclear programme of Iran.”![]()

Christoph Bluth, Professor of International Relations and Security, University of Bradford

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.