Contents:

- Binge drinking is a growing public health crisis − a neurobiologist explains how research on alcohol use disorder has shifted

2. Alcohol use disorder can be treated with an array of medications – but few people have heard of them

3. Can a drug like Ozempic help treat addictions to alcohol, opioids or other substances?

4. The rise of Ozempic: how surprise discoveries and lizard venom led to a new class of weight-loss drugs

Binge drinking is a growing public health crisis − a neurobiologist explains how research on alcohol use disorder has shifted

With the new Amy Winehouse biopic “Back to Black” in U.S. theaters as of May 17, 2024, the late singer’s relationship with alcohol and drugs is under scrutiny again. In July 2011, Winehouse was found dead in her flat in north London from “death by misadventure” at the age of 27. That’s the official British term used for accidental death caused by a voluntary risk.

Her blood alcohol concentration was 0.416%, more than five times the legal intoxication limit in the U.S. – leading her cause of death to be later adjusted to include “alcohol toxicity” following a second coroner’s inquest.

Nearly 13 years later, alcohol consumption and binge drinking remain a major public health crisis, not just in the U.K. but also in the U.S.

Roughly 1 in 5 U.S. adults report binge drinking at least once a week, with an average of seven drinks per binge episode. This is well over the amount of alcohol thought to produce legal intoxication, commonly defined as a blood alcohol concentration over 0.08% – on average, four drinks in two hours for women, five drinks in two hours for men.

Among women, days of “heavy drinking” increased 41% during the COVID-19 pandemic compared with pre-pandemic levels, and adult women in their 30s and 40s are rapidly increasing their rates of binge drinking, with no evidence of these trends slowing down. Despite efforts to comprehend the overall biology of substance use disorders, scientists’ and physicians’ understanding of the relationship between women’s health and binge drinking has lagged behind.

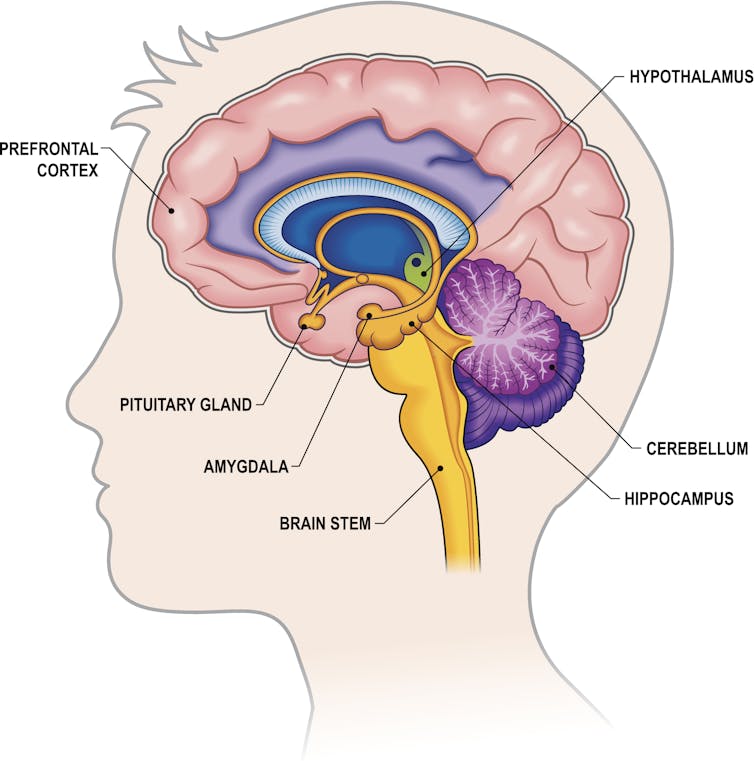

I am a neurobiologist focused on understanding the chemicals and brain regions that underlie addiction to alcohol. I study how neuropeptides – unique signaling molecules in the prefrontal cortex, one of the key brain regions in decision-making, risk-taking and reward – are altered by repeated exposure to binge alcohol consumption in animal models.

My lab focuses on understanding how things like alcohol alter these brain systems before diagnosable addiction, so that we can better inform efforts toward both prevention and treatment.

The biology of addiction

While problematic alcohol consumption has likely occurred as long as alcohol has existed, it wasn’t until 2011 that the American Society of Addiction Medicine recognized substance addiction as a brain disorder – the same year as Winehouse’s death. A diagnosis of an alcohol use disorder is now used over outdated terms such as labeling an individual as an alcoholic or having alcoholism.

Researchers and clinicians have made great strides in understanding how and why drugs – including alcohol, a drug – alter the brain. Often, people consume a drug like alcohol because of the rewarding and positive feelings it creates, such as enjoying drinks with friends or celebrating a milestone with a loved one. But what starts off as manageable consumption of alcohol can quickly devolve into cycles of excessive alcohol consumption followed by drug withdrawal.

While all forms of alcohol consumption come with health risks, binge drinking appears to be particularly dangerous due to how repeated cycling between a high state and a withdrawal state affect the brain. For example, for some people, alcohol use can lead to “hangxiety,” the feeling of anxiety that can accompany a hangover.

Repeated episodes of drinking and drunkenness, coupled with withdrawal, can spiral, leading to relapse and reuse of alcohol. In other words, alcohol use shifts from being rewarding to just trying to prevent feeling bad.

It makes sense. With repeated alcohol use over time, the areas of the brain engaged by alcohol can shift away from those traditionally associated with drug use and reward or pleasure to brain regions more typically engaged during stress and anxiety.

All of these stages of drinking, from the enjoyment of alcohol to withdrawal to the cycles of craving, continuously alter the brain and its communication pathways. Alcohol can affect several dozen neurotransmitters and receptors, making understanding its mechanism of action in the brain complicated.

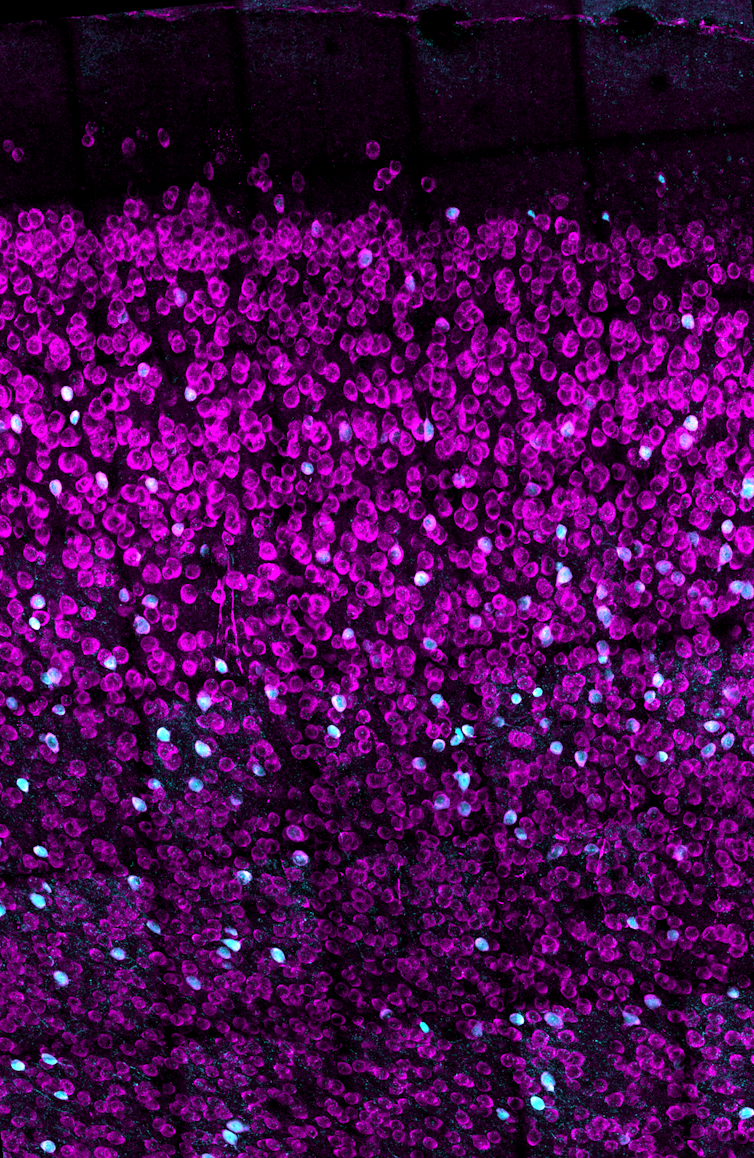

Work in my lab focuses on understanding how alcohol consumption changes the way neurons within the prefrontal cortex communicate with each other. Neurons are the brain’s key communicator, sending both electrical and chemical signals within the brain and to the rest of your body.

What we’ve found in animal models of binge drinking is that certain subtypes of neurons lose the ability to talk to each other appropriately. In some cases, binge drinking can permanently remodel the brain. Even after a prolonged period of abstinence, conversations between the neurons don’t return to normal.

These changes in the brain can appear even before there are noticeable changes in behavior. This could mean that the neurobiological underpinnings of addiction may take root well before an individual or their loved ones suspect a problem with alcohol.

Researchers like us don’t yet fully understand why some people may be more susceptible to this shift, but it likely has to do with genetic and biological factors, as well as the patterns and circumstances under which alcohol is consumed.

Women are forgotten

While researchers are increasingly understanding the medley of biological factors that underlie addiction, there’s one population that’s been largely overlooked until now: women.

Women may be more likely than men to have some of the most catastrophic health effects caused by alcohol use, such as liver issues, cardiovascular disease and cancer. Middle-aged women are now at the highest risk for binge drinking compared with other populations.

When women consume even moderate levels of alcohol, their risk for various cancers goes up, including digestive, breast and pancreatic cancer, among other health problems – and even death. So the worsening rates of alcohol use disorder in women prompt the need for a greater focus on women in the research and the search for treatments.

Yet, women have long been underrepresented in biomedical research.

It wasn’t until 1993 that clinical research funded by the National Institutes of Health was required to include women as research subjects. In fact, the NIH did not even require sex as a biological variable to be considered by federally funded researchers until 2016. When women are excluded from biomedical research, it leaves doctors and researchers with an incomplete understanding of health and disease, including alcohol addiction.

There is also increasing evidence that addictive substances can interact with cycling sex hormones such as estrogen and progesterone. For instance, research has shown that when estrogen levels are high, like before ovulation, alcohol might feel more rewarding, which could drive higher levels of binge drinking. Currently, researchers don’t know the full extent of the interaction between these natural biological rhythms or other unique biological factors involved in women’s health and propensity for alcohol addiction.

Looking ahead

Researchers and lawmakers are recognizing the vital need for increased research on women’s health. Major federal investments into women’s health research are a vital step toward developing better prevention and treatment options for women.

While women like Amy Winehouse may have been forced to struggle both privately and publicly with substance use disorders and alcohol, the increasing focus of research on addiction to alcohol and other substances as a brain disorder will open new treatment avenues for those suffering from the consequences.

For more information on alcohol use disorder, causes, prevention and treatments, visit the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.![]()

Nikki Crowley, Assistant Professor of Biology, Biomedical Engineering and Pharmacology, Penn State

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

****

Alcohol use disorder can be treated with an array of medications – but few people have heard of them

More than 29.5 million Americans ages 12 and up had alcohol use disorder – the medical term for the disease commonly known as alcoholism – in 2022, when the most recent national data was published.

The condition is characterized by a pattern of heavy alcohol consumption with loss of control over drinking despite negative social, occupational or health consequences.

Deaths from excessive alcohol use have sharply increased in recent years, to 178,000 in the United States in 2021, up from 138,000 five years earlier. The greatest increase occurred during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Alcohol is responsible for more deaths than overdoses from opioids and all other substances combined, and it accounts for 1 in 5 of all deaths of people ages 20 to 49. Alcohol-associated deaths occur from a variety of causes. These include alcohol’s long-term effects such as cancer, liver disease and heart disease as well as its short-term effects such as motor vehicle accidents, poisoning and suicide.

Many effective treatments exist for alcohol use disorder, including psychotherapy, peer support groups such as Alcoholics Anonymous and SMART Recovery, and medications. I’m a clinical psychologist and neuroscientist, and for the past 15 years, my research has focused on evaluating medications for alcohol use disorder.

Over that time, I have seen substantial changes in the scientific understanding and treatment of alcohol use disorder. I am optimistic that our existing medications can reach more people with this condition, that we can better target these medications to the patients most likely to benefit from them, and that new effective medications are on the horizon.

Alcohol use disorder is vastly undertreated

With the onset of the opioid epidemic in the past two decades, medications for opioid use disorder, such as methadone and buprenorphine, have entered the public consciousness. But medications for alcohol use disorder are less familiar to the public and used less frequently.

While 22% of patients with opioid use disorder receive medications to treat it, the rate of medication treatment for alcohol use disorder is much lower. Less than 10% of people with alcohol use disorder receive any treatment in any year, and less than 3% receive medications for it.

Regrettably, many people with alcohol use disorder don’t recognize the severity of their drinking and its effects on others, and many do not realize that effective medications are available.

Medications approved for alcohol use disorder

As of May 2024, three medications have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for treatment of alcohol use disorder. The oldest and best known of these medications is disulfiram – sold under the brand name Antabuse – a compound that was first used in the American rubber industry.

In 1937, a rubber plant physician observed that workers exposed to disulfiram displayed adverse reactions to alcohol, including nausea, vomiting and tachycardia – meaning fast heart rate. Subsequent research determined that disulfiram inhibits alcohol metabolism, leading to the accumulation of acetaldehyde. This causes many of the symptoms of a hangover immediately after alcohol ingestion, making drinking unpleasant.

Disulfiram is effective for reducing drinking but must be taken daily by mouth, which limits its utility if patients do not take it on this schedule.

A more recently FDA-approved – and more effective – medication for alcohol use disorder is the opioid receptor antagonist naltrexone. It blocks opioid receptors and prevents opioids – both “exogenous” opioid drugs and “endogenous” opioids produced in the brain – from activating these receptors.

It might be surprising that an opioid receptor antagonist is effective for treating alcohol use disorder. But, in fact, opioids play a key role in alcohol’s effect on the neurotransmitter dopamine, which underlies the pleasurable effects of alcohol and most other drugs.

Naltrexone reduces dopamine release from alcohol, blocking some of the pleasurable effects of drinking. Importantly, it also reduces alcohol craving, likely through its effects on dopamine that is released in response to cues, such as the sight, smell and taste of alcohol. Naltrexone is effective for reducing heavy drinking but less effective for complete abstinence from alcohol.

Naltrexone can be taken daily by mouth or injected once per month, making it a better option for patients who might struggle to take a daily oral medication. Interestingly, it also reduces heavy drinking when taken sporadically prior to anticipated drinking occasions. A similar opioid antagonist, nalmefene, is approved in the European Union for alcohol use disorder.

The third FDA-approved medication, acamprosate, also reduces alcohol cravings, but its molecular effects are less well understood. Results from European clinical trials have shown that it can help people reduce their drinking, but results from U.S. trials have been less positive.

‘Off-label’ medications

Several medications have demonstrated encouraging effects on drinking in randomized controlled trials but are not yet FDA-approved for alcohol use disorder. Instead, they are used “off-label,” meaning that physicians use their discretion to prescribe them for an unapproved indication. The most promising medications are approved for treating epilepsy.

These medications appear to be effective for alcohol use disorder in part by reducing symptoms of alcohol withdrawal, a dangerous condition that develops among some people following the abrupt cessation of heavy drinking. In its most severe form, alcohol withdrawal causes hyperreactivity of the autonomic nervous system, auditory and visual hallucinations and seizures. These medications include gabapentin, topiramate and baclofen, the latter of which is approved in France for alcohol use disorder.

Precision medicine

Regrettably, both the FDA-approved and off-label medications for alcohol use disorder have relatively small effects on alcohol consumption. On average, these medications will cause people who drink heavily – meaning four or more drinks in a day for women, five or more for men – most days of the week to do so one or two days less per week. However, this average varies significantly between patients – some see a large effect, and some see no benefit.

An important recent focus of research, funded by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, on alcohol use disorder medications has been the application of a “precision medicine” approach to identify patients for whom a particular medication is more likely to have a large effect.

For example, my work and others’ has found that people who both drink heavily and smoke cigarettes are more likely to benefit from naltrexone. This may be because the additive effects of alcohol and nicotine on dopamine release in reward-related brain regions makes these people particularly likely to benefit from a medication that can block dopamine release by alcohol. Naltrexone also appears to be more effective among people whose drinking is motivated by a desire for the positive, rewarding effects of alcohol, consistent with its ability to reduce these effects.

Finally, recent research suggests that gabapentin may be more effective in people with a history of alcohol withdrawal. Genes that predict medication effects are also being evaluated, but to date none has had consistent effects across studies.

On the horizon

The search for robustly effective medications to treat alcohol use disorder is a significant area of current research. The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism funds a multisite research program, in which my laboratory participates, that has evaluated a number of promising candidate medications in Phase 2 and Phase 3 clinical trials. The FDA typically requires medications to demonstrate efficacy in at least two Phase 3 trials prior to approval for a new purpose.

A resurgence of interest in psychedelic compounds in psychiatry has led to preliminary data suggesting that psilocybin, the active ingredient in hallucinogenic mushrooms, may reduce drinking when paired with psychotherapy.

Finally, anecdotal reports of reduced interest in alcohol among patients taking GLP-1 agonists – medications that mimic the action of glucagonlike peptide 1 (GLP-1), a hormone produced by the body after eating – have prompted intense interest in the potential of these medications to treat alcohol use disorder. These include Ozempic and Wegovy, which are FDA-approved for diabetes and weight loss. My laboratory and several others are conducting trials of these medications, with results expected in the next one to two years.

Alcohol use disorder is a devastating condition for which better treatments are desperately needed. Approved and off-label medications are currently available. As research into new medications continues, patients should seek providers who use evidence-based treatments to have the greatest likelihood of success in gaining control over their drinking.![]()

Joseph P. Schacht, Associate Professor of Psychiatry, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

****

Can a drug like Ozempic help treat addictions to alcohol, opioids or other substances?

Hundreds of thousands of people worldwide are taking drugs like Ozempic to lose weight. But what do we actually know about them? This month, The Conversation’s experts explore their rise, impact and potential consequences.

Semaglutide (sold as Ozempic, Wegovy and Rybelsus) was initially developed to treat diabetes. It works by stimulating the production of insulin to keep blood sugar levels in check.

This type of drug is increasingly being prescribed for weight loss, despite the fact it was initially approved for another purpose. Recently, there has been growing interest in another possible use: to treat addiction.

Anecdotal reports from patients taking semaglutide for weight loss suggest it reduces their appetite and craving for food, but surprisingly, it also may reduce their desire to drink alcohol, smoke cigarettes or take other drugs.

But does the research evidence back this up?

Animal studies show positive results

Semaglutide works on glucagon-like peptide-1 receptors and is known as a “GLP-1 agonist”.

Animal studies in rodents and monkeys have been overwhelmingly positive. Studies suggest GLP-1 agonists can reduce drug consumption and the rewarding value of drugs, including alcohol, nicotine, cocaine and opioids.

Out team has reviewed the evidence and found more than 30 different pre-clinical studies have been conducted. The majority show positive results in reducing drug and alcohol consumption or cravings. More than half of these studies focus specifically on alcohol use.

However, translating research evidence from animal models to people living with addiction is challenging. Although these results are promising, it’s still too early to tell if it will be safe and effective in humans with alcohol use disorder, nicotine addiction or another drug dependence.

What about research in humans?

Research findings are mixed in human studies.

Only one large randomised controlled trial has been conducted so far on alcohol. This study of 127 people found no difference between exenatide (a GLP-1 agonist) and placebo (a sham treatment) in reducing alcohol use or heavy drinking over 26 weeks.

In fact, everyone in the study reduced their drinking, both people on active medication and in the placebo group.

However, the authors conducted further analyses to examine changes in drinking in relation to weight. They found there was a reduction in drinking for people who had both alcohol use problems and obesity.

For people who started at a normal weight (BMI less than 30), despite initial reductions in drinking, they observed a rebound increase in levels of heavy drinking after four weeks of medication, with an overall increase in heavy drinking days relative to those who took the placebo.

There were no differences between groups for other measures of drinking, such as cravings.

In another 12-week trial, researchers found the GLP-1 agonist dulaglutide did not help to reduce smoking.

However, people receiving GLP-1 agonist dulaglutide drank 29% less alcohol than those on the placebo. Over 90% of people in this study also had obesity.

Smaller studies have looked at GLP-1 agonists short-term for cocaine and opioids, with mixed results.

There are currently many other clinical studies of GLP-1 agonists and alcohol and other addictive disorders underway.

While we await findings from bigger studies, it’s difficult to interpret the conflicting results. These differences in treatment response may come from individual differences that affect addiction, including physical and mental health problems.

Larger studies in broader populations of people will tell us more about whether GLP-1 agonists will work for addiction, and if so, for whom.

How might these drugs work for addiction?

The exact way GLP-1 agonists act are not yet well understood, however in addition to reducing consumption (of food or drugs), they also may reduce cravings.

Animal studies show GLP-1 agonists reduce craving for cocaine and opioids.

This may involve a key are of the brain reward circuit, the ventral striatum, with experimenters showing if they directly administer GLP-1 agonists into this region, rats show reduced “craving” for oxycodone or cocaine, possibly through reducing drug-induced dopamine release.

Using human brain imaging, experimenters can elicit craving by showing images (cues) associated with alcohol. The GLP-1 agonist exenatide reduced brain activity in response to an alcohol cue. Researchers saw reduced brain activity in the ventral striatum and septal areas of the brain, which connect to regions that regulate emotion, like the amygdala.

In studies in humans, it remains unclear whether GLP-1 agonists act directly to reduce cravings for alcohol or other drugs. This needs to be directly assessed in future research, alongside any reductions in use.

Are these drugs safe to use for addiction?

Overall, GLP-1 agonists have been shown to be relatively safe in healthy adults, and in people with diabetes or obesity. However side effects do include nausea, digestive troubles and headaches.

And while some people are OK with losing weight as a side effect, others aren’t. If someone is already underweight, for example, this drug might not be suitable for them.

In addition, very few studies have been conducted in people with addictive disorders. Yet some side effects may be more of an issue in people with addiction. Recent research, for instance, points to a rare risk of pancreatitis associated with GLP-1 agonists, and people with alcohol use problems already have a higher risk of this disorder.

Other drugs treatments are currently available

Although emerging research on GLP-1 agonists for addiction is an exciting development, much more research needs to be done to know the risks and benefits of these GLP-1 agonists for people living with addiction.

In the meantime, existing effective medications for addiction remain under-prescribed. Only about 3% of Australians with alcohol dependence, for example, are prescribed medication treatments such as like naltrexone, acamprosate or disulfiram. We need to ensure current medication treatments are accessible and health providers know how to prescribe them.

Continued innovation in addiction treatment is also essential. Our team is leading research towards other individualised and effective medications for alcohol dependence, while others are investigating treatments for nicotine addiction and other drug dependence.

Read the other articles in The Conversation’s Ozempic series here.![]()

Shalini Arunogiri, Addiction Psychiatrist, Associate Professor, Monash University; Leigh Walker, , Florey Institute of Neuroscience and Mental Health, and Roberta Anversa, , The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

*****

The rise of Ozempic: how surprise discoveries and lizard venom led to a new class of weight-loss drugs

Hundreds of thousands of people worldwide are taking drugs like Ozempic to lose weight. But what do we actually know about them? This month, The Conversation’s experts explore their rise, impact and potential consequences.

Every now and then, scientists develop treatments that end up being even more popular for another condition entirely. Think of Viagra, originally for high blood pressure, now used for erectile dysfunction. Or thalidomide, a dangerous morning sickness treatment that is now a valuable cancer treatment.

The blockbuster drug Ozempic was originally developed to treat type 2 diabetes, a condition that results in too much glucose, or sugar, in the blood. This is because the body can’t effectively use the insulin it produces.

In the 1980s, medications to treat type 2 diabetes would often lead to weight gain, which could worsen the condition. Patients would end up needing insulin replacement therapy.

But the class of drugs Ozempic belongs to would change this and generate A$21 billion of sales in 2023 alone for its maker.

The start of the journey

In the 19th century, French physiologist Claude Barnard sought to explain why large amounts of glucose (the main sugar in your blood) can be taken orally, whereas if glucose is given intravenously, small amounts overload the body’s systems.

In 1922 Frederick Banting and Charles Best discovered the hormone insulin, which controls glucose use. But this didn’t explain the difference between oral and intravenous glucose tolerance.

In 1932, Belgian Jean La Barre identified there was a hormone in the gastrointestinal tract responsible for stimulating insulin secretion. La Barre named this “incrétine” (incretin), a blending of ingestion and secretin, and suggested it may be a diabetes treatment.

In the 1960s, researchers showed the incretin effect was responsible for about two-thirds of people’s insulin response. New and sensitive ways to measure blood hormone levels then allowed researchers to show a hormone called GIP (glucose‐dependent insulinotropic polypeptide) was partly responsible for the incretin effect.

This meant there must be another hormone, whose discovery had to wait until the age of cloning in the 1980s. Cloning the GLP-1 (glucagon-like peptide 1) gene, biochemist Svetlana Mojsov demonstrated it stimulated pancreatic insulin secretion at 1/100th of the concentration needed for GIP. So GLP-1 was identified as the other incretin responsible for people’s insulin response.

The glucose-lowering effects of GIP and GLP-1 excited scientists, but they couldn’t be used as medicines because they metabolised too quickly in the body.

Enter a poisonous lizard

In the 1980s John Pisano, a biochemist with a penchant for venoms, and a young gastroenterologist Jean-Pierre Raufman were working with poisonous lizard venom from the Gila monster, a slow-moving reptile native to the south of the United States and north of Mexico. By the 1990s, Pisano, Raufman and colleague John Eng identified a hormone-like molecule they called exendin-4. This stimulated insulin secretion via action at the same receptor as GLP-1.

Excitingly, exendin-4 was not quickly metabolised by the body, and so might be useful as a diabetic therapeutic.

Eng was convinced this would work, but pharmaceutical companies didn’t want to give people a hormone mimic from a venomous lizard. Even the medical centre where Eng was working wouldn’t help fill the patent.

Eventually he and Raufman convinced a small start-up called Amylin Pharmaceuticals. Amylin quickly showed synthetic exendin-4 rapidly normalised blood glucose in type 2 diabetic mice. Exendin-4 then proved safe and effective in humans, leading to the 2005 US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of exenatide, under the name Byetta.

It soon became evident that many taking Byetta were experiencing sustained weight-loss (around 5%, but with some experiencing much more), with the benefit of reversing their diabetic symptoms.

News of this weight-loss effect spread and within six months Byetta was being used off-label for weight-loss, foreshadowing the widespread use of Ozempic.

From a lizard toxin to Ozempic

Meanwhile, Danish pharmaceutical company Novo Nordisk had been developing a long-acting GLP-1-mimicking drug, as it had done for insulin in the past. Its research showed high levels of GLP-1 could correct diabetes in mice and they would lose weight.

During the 1990s, there was controversy over how GLP-1 led to weight loss, however it later became clear there were GLP-1 receptors in the brain that suppressed the desire to eat.

Novo Nordisk’s new GLP-1 drug had been designed to be long-acting. One consequence of this design was it was better at accessing brain GLP-1 receptors.

This new drug, liraglutide, approved as Victoza in 2010 in the United States, was better for weight-loss than Byetta (typically 10% weight-loss), but still needed daily injections.

Daily injections aren’t popular, and Novo Nordisk’s team had been working on an even longer acting drug, semaglutide, approved as Ozempic in 2017 as a once-weekly injection. It had improved brain GLP-1 receptor targeting, further enhancing weight loss.

Due to its safety profile and weight-loss efficacy (of around 15%), a higher dose of semaglutide gained FDA approval as Wegovy in 2021 as a stand-alone obesity treatment.

So how do these drugs actually work?

Your gastrointestinal tract contains specialised cells that measure the quantities and qualities of incoming food (as well as the absence of food) and communicates this with the rest of your body, including your brain.

You may remember Pavlov’s dogs, which were conditioned to expect a meal at the sound of a bell, kind of like what happens when you’re presented with a delicious plate of food. Not only does your brain make you salivate, it also starts the process of releasing digestive juices and even causes insulin levels to rise.

Ozempic and other GLP-1-mimicking drugs slow gastric emptying, which increases your sense of fullness.

Insulin secretion increases because there are nerves with GLP-1 receptors close to the wall of your gastrointestinal tract. This sends messages to the unconscious part of your brain that interpret these and send messages back (via nerves) to your gastrointestinal tract and pancreas to secrete insulin.

What about the new drug, Mounjaro?

Remember the other incretin hormone, GIP? GIP also suppresses appetite and can stimulate insulin secretion, but not as well as GLP-1.

Unlike GLP-1, GIP increases the secretion of another hormone, glucagon. Glucagon promotes energy use but also increases blood glucose during periods of fasting. Many felt the actions of glucagon needed to be blocked for effective anti-diabetic and weight-loss medications. But this doesn’t seem to be the case.

German physician and scientist Matthias Tschöp and American chemist Richard DiMarchi, who had met at Eli Lilly, were working on synthetic versions of glucagon to treat sudden drops in blood glucose when they unexpectedly found long-term dosing caused weight-loss in obese mice. Since GLP-1 and GIP are closely related, they thought it might be possible to target both receptors with a single drug.

In 2013, they showed a dual-acting drug was effective in obese mice. This led to the development of tirzepatide (Mounjaro and Zepbound, which is a slightly higher dose). Compared with GLP-1 drugs, it also stimulated metabolism, particularly fat use.

Clinical trials of Zepbound showed it to be more effective than Ozempic for weight-loss (typically 18% of body weight). Mounjaro was approved for type 2 diabetes in 2022 and Zepbound was approved for obesity in 2023.

GIP and GLP-1 are similar to glucagon so Tschöp and DiMarchi set out to develop a drug targeting all three. In 2014 they showed that a triple-targeting drug, which would become retatrutide, was superior in obese mice. Now in mid-stage clinical trials, Eli Lilly’s drug retatrutide (once-weekly injection) results in a weight loss of around 24% in obese adults.

Why can’t you take them in a pill?

These current drugs are big molecules (peptides) and for this reason must be injected as they’re not absorbed effectively in the gut.

In 2019, Novo Nordisk managed to reformulate semaglutide so some would make it through the stomach intact and enough got absorbed (about 1%) to be clinically effective. It repackaged this as Rybelsus.

But although enough of the drug gets into circulation to assist with type 2 diabetes, it requires 100 times the dose for weight-loss.

Both Pfizer and Eli Lilly have small-molecule drugs targeting the GLP-1 receptor. These are designed to be taken orally, are formulated for once-a-day, and would be less expensive than Ozempic or Mounjaro.

Pfizer’s drug, Danuglipron, has had mixed success in clinical trials. One formulation has been discontinued because of high clinical-trial drop-out rates (due to gastrointestinal side-effects such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea and pain). But both formulations do control type 2 diabetes and lead to about 10% weight-loss.

Eli Lilly’s trials of Orforglipron have shown promising weight-loss for obese participants of about 10%.

Plenty of weight-loss drugs have failed, too

Anti-obesity drugs with other targets – such as those sold under the brand names Qsymia, Contrave, Reductil and Accomplia – resulted in weight loss (typically less than 10%) but were accompanied by side effects such as increased heart rate, heart disease and psychological safety concerns such as anxiety and suicidal thoughts.

This resulted in market withdrawals and scared participants away from clinical trials.

Ozempic’s safety profile and effectiveness has reversed this, though there are a number of potential side effects (mainly gastric upsets) and people who stop taking Ozempic typically have big weight rebounds. Clinical trial recruitment is becoming easier and many pharmaceutical companies are playing catch up.

Read the other articles in The Conversation’s Ozempic series here.![]()

Sebastian Furness, ARC Future Fellow, School of Biomedical Sciences, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.