Why the cost of water for poor Black Detroit voters may be key to Kamala Harris winning – or losing – Michigan

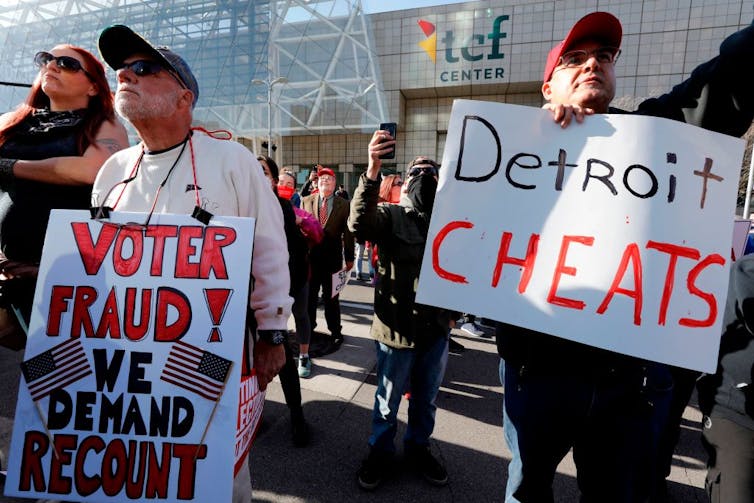

The threat of violence was in the air at the TCF Center in Detroit on Nov. 5, 2020, after former President Donald Trump claimed that poll workers in the city were duplicating ballots and that there was an unexplained delay in delivering them for counting.

Both claims were later debunked.

Emboldened by Trump’s rhetoric, dozens of mainly white Republican Trump supporters banged on doors and windows at the vote-tallying center, chanting, “Stop the count!”

But Detroit’s poll workers, most of them Black, finished tallying the ballots. In the end, 95% of voters in Detroit, the largest city in Michigan and the one with the most African Americans – 78% of residents – cast their ballot for Joe Biden, the Democratic presidential nominee.

We are political science and sociology professors at Wayne State University in Detroit, where we teach about the relationship between race, religion and politics. Our research has identified two groups of African American voters in Detroit – one that will clearly support Kamala Harris and another that is critical for her to win over if she wants to win Michigan.

Firmly in Kamala’s camp

Those African Americans most likely to vote for Harris in November 2024 are strong Democratic partisans who feel that Trump threatens Black political strides toward democracy.

Harris can also rely on members of Detroit nonprofits like the NAACP, Black Greek organizations, and religious congregations connected to advocacy groups such as MOSES, the Michigan Welfare Rights Organization and the Fannie Lou Hamer Political Action Committee.

But what of the working-class and poor Black Detroit residents who tend not to be as heavily connected to the Democratic Party and are less involved with grassroots organizations that advocate on their behalf? These are the individuals who inconsistently vote in presidential elections but that recent history has shown could be key to winning Michigan, a crucial swing state.

Small bumps in voter turnout matter

While Detroit’s voters helped Biden win the state and the White House in 2020, such was not the case for Hillary Clinton in 2016.

The difference was due in part to lower voter turnout.

In 2016, 95% of the Detroiters who voted in the presidential election opted for Democratic nominee Clinton. Still, she lost Michigan by 0.2% – fewer than 11,000 votes.

One contributing factor to the difference in Michigan’s presidential election outcomes between 2016 and 2020 was Detroit’s lower voter turnout in 2016 relative to 2020.

In 2016, Detroit’s voter turnout was 48.6% – compared with 50.88% in 2020. Detroit’s higher voter turnout in 2020 contributed to Biden winning Michigan in 2020 by a margin of less than 3%.

Let us suppose that 2016 and 2020 are guides to 2024. In that case, Harris’ ability to win Michigan in November is less about losing Black voters to Trump than her ability to motivate Black voters in Detroit and across the state to show up to the polls. This is key because African Americans, at roughly 13% of the U.S. electorate, overwhelmingly vote Democratic when they vote.

In many respects, 2020 served as a referendum on Trump’s management of the COVID-19 epidemic, which had an outsize impact on Black Americans, who were nearly twice as likely as white Americans to die from the virus.

That election also served as a referendum on Trump’s racial politics. During the summer of 2020, with the nation embroiled in protests against anti-Black police violence, Trump framed the protesters as anti-American and criminals.

It therefore makes sense that in 2020, the vast majority – over 90% – of African Americans nationwide stated that concerns about racism and COVID-19 motivated their vote.

Looking toward the 2024 election, a question that looms large is: Will the Black voter turnout in Detroit be closer to 2016 or 2020?

Protesters in Detroit rally to support the 2020 election results and other causes. Stephen Zenner/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images

Protesters in Detroit rally to support the 2020 election results and other causes. Stephen Zenner/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images

Quality-of-life issues key in 2024

In early 2024, quality-of-life concerns about crime, vacant buildings and affordable housing were the top three issues that Detroit residents want their city and the U.S. government to address, according to the Detroit Metro Area Communities Study.

Similarly, an August 2024 poll by Suffolk University and USA Today found that roughly 6 in 10 Black voters in Michigan mentioned the rising cost of living, crime and health care as motivating their willingness to vote.

These same issues are at the top of Black voters’ minds nationwide. A February 2024 Kaiser Family Foundation Poll reported that over 90% of Black Americans believe that the presidential candidates should discuss the rising cost of living and health care, and three-quarters believe they should discuss protecting the Affordable Care Act.

The 2024 election is a crucial moment for these issues to be addressed.

Detroit’s ongoing water concerns

When it comes to working-class and low-income people in Detroit, a key cost-of-living issue is the cost of water.

As Detroit’s city government attempted to shore up its finances following its 2013 bankruptcy, it began to more aggressively target residents who were delinquent in their water bills. The city shut off the water of more than 141,000 residents between 2013 and 2020.

As of 2023, 27% of Detroit households – about 170,000 people – are at risk of having their water shut off due to unpaid water bills. The 60,000 people in arrears for unpaid water bills owe an average of US$700.

In response to this crisis, local grassroots organizations, many of them faith-based, like the Michigan Welfare Rights Organization, organized community members to push for legislation that ties water bill rates to residents’ income.

In October 2023, Michigan Democrat State Sen. Stephanie Chang introduced a series of bills to do just that, but the bills have languished in the Housing and Human Services Senate Committee.

An April 2024, a metropolitan Detroit survey we conducted revealed that 87% of Black Detroiters support these water affordability bills.

Harris’ ability to generate Black voter turnout in Michigan that’s similar to 2020, particularly in Detroit, may hinge on her ability to articulate the federal government’s plans to address cost-of-living concerns. This includes securing federal grants for cities, like Detroit, to subsidize water rates for its working-class and low-income residents.

While Harris did not explicitly address the issue of water affordability during her Labor Day visit to Detroit, she did tell the audience that, unlike Trump, she would not impose a national sales tax on everyday items. She also pledged to keep prescription drug prices affordable and strengthen the Affordable Care Act.

Will Harris’ message that Detroiters’ cost of living will fare worse under a Trump administration be enough to energize Black Detroiters to vote for her?

This is a crucial question for her 2024 campaign in Michigan, where she and Trump are in a statistical tie among likely voters.![]()

Ronald Brown, Professor of Political Science, Wayne State University and R. Khari Brown, Professor of Sociology, Wayne State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.